Better Code for Better Requirements

Even if your code is of the highest quality, if it’s not reflecting what was specified in the requirements, you may have built perfectly useless code.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeQuality is a very hot topic in the DevOps and Continuous Delivery era. “Quality with speed” is the theme of the hour. But most development and testing teams have different views on what quality means to them.

Looking back at my days as a professional developer, I remember being tasked to follow the company coding style guide. This described the design principles and the code convention all

the developers should follow so that we wrote consistent code. Thus when a change request came in, anyone could read the code and make the edits, and we could minimize maintenance.

Then there were the weekly reviews where we would get together with a peer and go through the code to ensure we understood it and were following the style guide. If the code checked out, we then thought we had quality code.

But did that mean the applications we built were high quality? No!

Setup

I’ve worked with plenty of agile dev teams that have adopted DevOps and achieved Continuous Delivery. These teams typically create basic, sometimes throwaway code just so they can

quickly push a build out to users to get feedback and make quick adjustments. Of course this approach generates technical debt; however, at this stage, speed is more valued than code that is perfectly written according to any style guide.

Upon seeing positive feedback from users, these teams start constantly refactoring the code to keep technical debt at manageable levels. Otherwise, all the speed they’ve gained to roll out the first builds is lost as the code grows and becomes hard to change due to the technical debt accrued. The ultimate consequence: team capacity and velocity for future iterations is decreased, taking everyone back to square one — with not only less- than-adequate code, but also an application that users don’t like.

So to keep improving their code in such a mature environment, these teams use code quality tools to profile the code and determine where to focus refactoring efforts first. This helps them build things right. But no matter how good the code gets, the user may still think the application sucks, simply because they were not building the right things in the eyes of the user. There is a difference between the two, and in my experience, this is a huge gap in most Continuous Delivery initiatives.

So what’s the missing link? Requirements. The code may be of the highest quality, but if it’s not reflecting what was specified in the requirements, you may have built perfectly useless code.

Louis Srygley has an apt description for this:

“Without requirements and design, programming is the art of adding bugs to an empty text file.”

Building Things Right vs. Building the Right Things

The use of diagrams such as visual flowcharts to represent requirements is something that helps analysts, product owners, developers, testers, and op engineers. Diagrams are a great communication tool to remove ambiguities and prevent misinterpretations by each of these stakeholders — ultimately leading to fewer defects in the code, as the visual flowcharts enable all stakeholders to have a common understanding from the get-go.

The key is to change our mindset of using “testing” as the only means to achieve application quality.

With Continuous Delivery, we’re realizing that although we can run unlimited automated tests at all levels to find defects, this approach will always be reactive and more costly than tests that always pass because there were no defects. That means we have prevented defects from being written into the code, which consequently means we have built quality into the application itself.

Martin Thompson says it best:

“It took us centuries to reach our current capabilities in civil engineering, so we should not be surprised by our current struggles with software.”

We are on the right track. Tools have evolved and continue to evolve at a never-before-seen pace. The area that has been lagging in terms of advanced and easy-to-use tooling is the requirements- gathering and definition process. Martin Thompson also has a good quote on that:

“If we look to other engineering [disciplines], we can see the use of tooling to support the process of delivery rather than imposing a process on it.”

Look at civil engineering. CAD (computer-aided design) software revolutionized the designing of buildings and structures. We’ve been missing a CAD-like tool for software engineering, but now we are at a point where we have highly advanced and easy-to-use solutions to fill that gap.

Building Quality Into the Code = Application Quality

It is very common today for a product owner to draw an initial sketch on a whiteboard describing what she wants built. That sketch is then further refined through multiple iterations until the product owner is satisfied and accepts it.

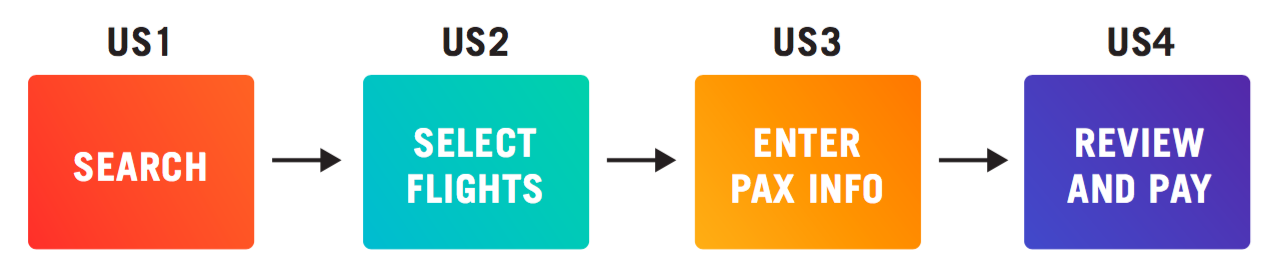

That initial sketch for a simple Flight Booking Path example could look something like this:

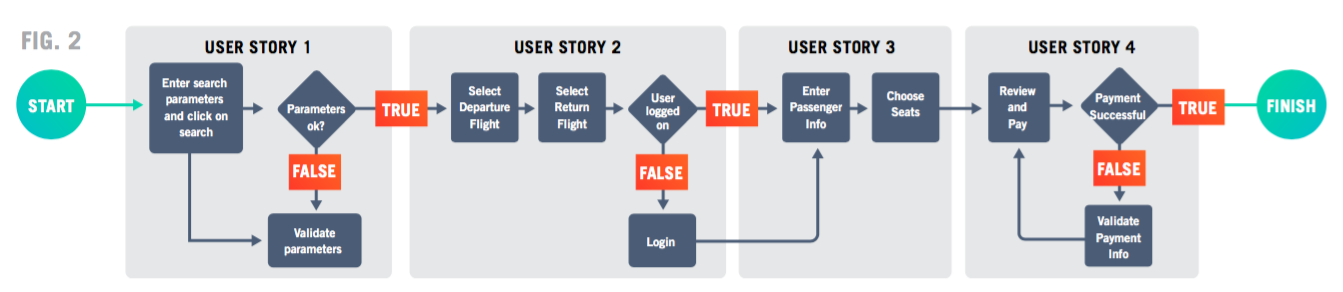

Then, through multiple conversations with the product owner, developers, testers, and other stakeholders, the person assigned to formally model the Epic could come up with this model:

As you can see, those conversations caused a few additional process steps to be added as the model was formalized. We now know that the product owner wants the user to select the departure flight first and then select the return flight. It is also clear that before going to the passenger information step, the user must be prompted to log in. Lastly, it was clarified that the seats must be chosen only after the passenger information has been entered in the application.

Through the mere representation of the Epic in a visual model, ambiguities are removed and defects are prevented from entering the application code. Which means testing is truly “shifting left” in the lifecycle. And we’re already starting to “build quality in” the application.

The visual model of the Flight Booking Path Epic becomes the foundational layer for other stakeholders in the lifecycle.

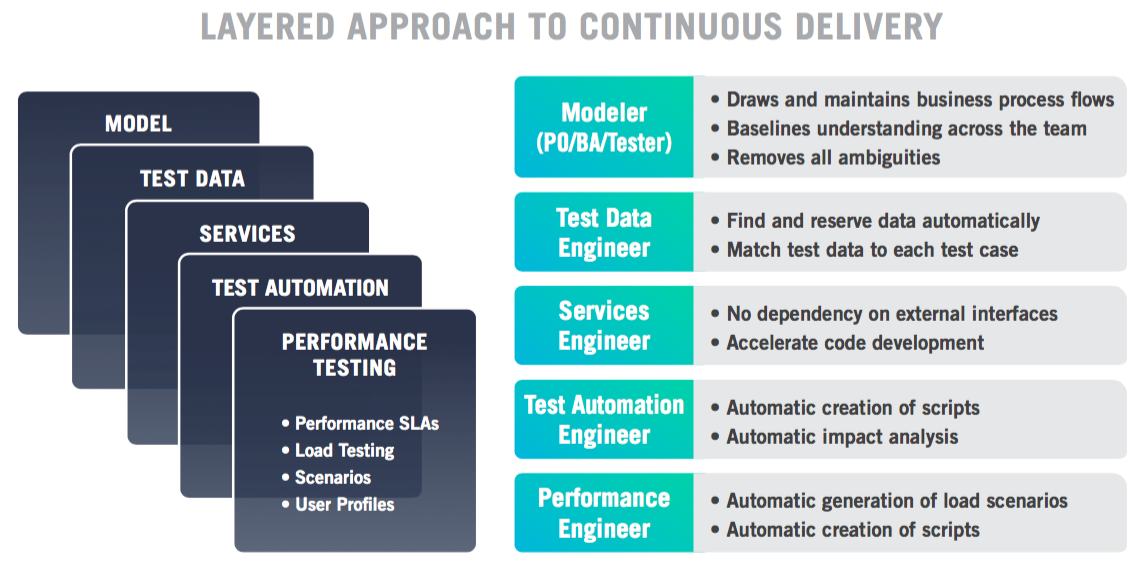

A CAD-like tool in software engineering helps us build a multilayered visual model of the requirements. These layers are tied together, and just like the CAD tools in civil engineering, the tool maintains full traceability across all layers as shown below.

So if there is a change to any of those layers, the impact is automatically identified and communicated to the owner of each impacted layer, prompting the owner for a decision to address that impact.

From that visual model, the tool can then automatically:

- Generate manual test cases.

- Find, copy, mask, or synthetically generate the test data required for each test case.

- Generate request/response pairs as well as provision virtual services for test cases to be able to run.

- Generate test automation scripts in any language according to the test automation tools being used by the team.

So while developers must continue to invest in increasing code quality to build things right, the use of a CAD-like tool in software engineering not only accelerates the software lifecycle (i.e., speed), but it also ensures developers are building the right things (i.e., quality) from the beginning by providing unambiguous requirements to all stakeholders across the SDLC.

More DevOps Goodness

If you'd like to see other articles in this guide, be sure to check out:

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments