Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery for Database Changes

This article takes a look at continuous integration and continuous delivery for database changes and also looks at version control database artifacts.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeDevOps proposes Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery (CI/CD) solutions for software project management. In CI/CD, the process of software development and operations falls into a cyclical feedback loop, which promotes not only innovation and improvements but also makes the product quickly adapt to the changing needs of the market. So, it becomes easy to cater to the needs of the customer and garner their satisfaction. The development team that adopts the culture becomes agile, flexible, and adaptive (called the Agile development team) in building an incremental quality product that focuses on continuous improvement and innovation.

One of the key areas of CI/CD is to address changes. The evolution of software also has its effect on the database as well. Database change management primarily focuses on this aspect and can be a real hurdle in collaboration with DevOps practices which is advocating automation for CI/CD pipelines. Automating database change management enables the development team to stay agile by keeping database schema up to date as part of the delivery and deployment process. It helps to keep track of changes critical for debugging production problems.

The purpose of this article is to highlight how database change management is an important part of implementing Continuous Delivery and recommends some processes that help streamline application code and database changes into a single delivery pipeline.

Continuous Integration

One of the core principles of an Agile development process is Continuous Integration. Continuous Integration emphasizes making sure that code developed by multiple members of the team is always integrated. It avoids the “integration hell” that used to be so common during the days when developers worked in their silos and waited until everyone was done with their pieces of work before attempting to integrate them. Continuous Integration involves independent build machines, automated builds, and automated tests. It promotes test-driven development and the practice of making frequent atomic commits to the baseline or master branch or trunk of the version control system.

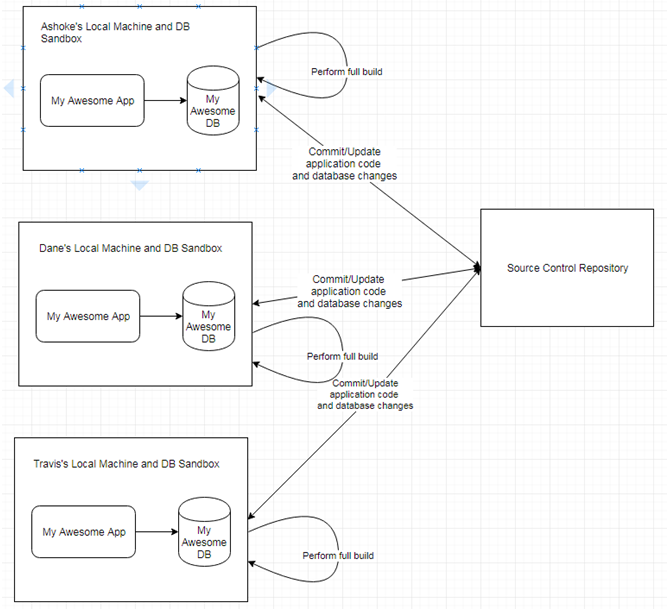

Figure 1: A typical Continuous Integration process

The diagram above illustrates a typical Continuous Integration process. As soon as a developer checks in code to the source control system, it will trigger a build job configured in the Continuous Integration (CI) server. The CI Job will check out code from the version control system, execute a build, run a suite of tests, and deploy the generated artifacts (e.g., a JAR file) to an artifact repository. There may be timed CI jobs to deploy the code to the development environment, push details out to a static analysis tool, run system tests on the deployed code, or any automated process that the team feels is useful to ensure that the health of the codebase is always maintained. It is the responsibility of the Agile team to make sure that if there is any failure in any of the above-mentioned automated processes, it is promptly addressed and no further commits are made to the codebase until the automated build is fixed.

Continuous Delivery

Continuous Delivery takes the concept of Continuous Integration a couple of steps further. In addition to making sure that different modules of a software system are always integrated, it also makes sure that the code is always deployable (to production). This means that in addition to having an automated build and a completely automated test suite, there should be an automated process of delivering the software to production. Using the automated process, it should be possible to deploy software on short notice, typically within minutes, with the click of a button. Continuous Delivery is one of the core principles of DevOps and offers many benefits including predictable deploys, reduced risk while introducing new features, shorter feedback cycles with the customer, and overall higher quality of software.

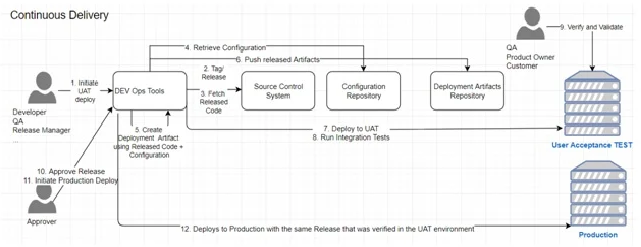

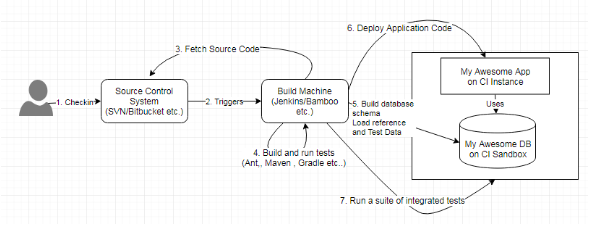

Figure 2: A typical Continuous Delivery process

The above diagram shows a typical Continuous Delivery process. Please note that the above-illustrated Continuous Delivery process assumes that a Continuous Integration process is already in place. The above diagram shows 2 environments: e.g., User Acceptance Test (UAT) and production. However, different organizations may have multiple staging environments (Quality Assurance or QA, load testing, pre-production, etc.) before the software makes it to the production environment. However, it is the same codebase, and more precisely, the same version of the codebase that gets deployed to different environments. Deployment to all staging environments and the production environment are performed through the same automated process. There are many tools available to manage configurations (as code) and make sure that deploys are automatic (usually self-service), controlled, repeatable, reliable, auditable, and reversible (can be rolled back). It is beyond the scope of this article to go over those DevOps tools, but the point here is to stress the fact that there must be an automated process to release software to production on demand.

Database Change Management Is the Bottleneck

Agile practices are pretty much mainstream nowadays when it comes to developing application code. However, we don’t see as much adoption of agile principles and continuous integration in the area of database development. Almost all enterprise applications have a database involved and thus project deliverables would involve some database-related work in addition to application code development. Therefore, slowness in the process of delivering database-related work - for example, a schema change - slows down the delivery of an entire release.

In this article, we would assume the database to be a relational database management system. The processes would be very different if the database involved is a non-relational database like a columnar database, document database, or a database storing data in key-value pairs or graphs.

Let me illustrate this scenario with a real example: here is this team that practices Agile software development methodologies. They follow a particular type of Agile called Scrum, and they have a 2-week Sprint. One of the stories in the current sprint is the inclusion of a new field in the document that they interchange with a downstream system. The development team estimated that the story is worth only 1 point when it comes to the development of the code. It only involves minor changes in the data access layer to save the additional field and retrieve it later when a business event occurs and causes the application to send out a document to a downstream system. However, it requires the addition of a new column to an existing table. Had there been no database changes involved, the story could have been easily completed in the current sprint, but since there is a database change involved, the development team doesn’t think it is doable in this sprint.

Why? Because a schema change request needs to be sent to the Database Administrators (DBA). The DBAs will take some time to prioritize this change request and rank this against other change requests that they received from other application development teams. Once the DBAs make the changes in the development database, they will let the developers know and wait for their feedback before they promote the changes to the QA environment and other staging environments, if applicable. Developers will test changes in their code against the new schema. Finally, the development team will closely coordinate with the DBAs while scheduling delivery of application changes and database changes to production.

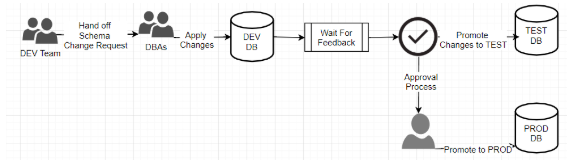

Figure 3: Manual or semi-automated process in delivering database changes

Please note in the diagram above that the process is not triggered by a developer checking in code and constitutes a handoff between two teams. Even if the deployment process on the database side is automated, it is not integrated with the delivery pipeline of application code.

The changes in the application code are directly dependent on the database changes, and they together constitute a release that delivers a useful feature to the customer. Without one change, the other change is not only useless but could potentially cause regression. However, the lifecycle of both of these changes is completely independent of each other. The fact that the database and codebase changes follow independent life cycles and the fact that there are handoffs and manual checkpoints involved, the Continuous Delivery process, in this example, is broken.

Recommendations To Fix CI/CD for Database Changes

In the following sections, we will explain how this can be fixed and how database-related work including data modeling and schema changes, etc., can be brought under the ambit of the Continuous Delivery process.

DBAs Should Be a Part of the Cross-Functional Agile Team

Many organizations have their DBAs split into broadly two different types of roles based on whether they help to build a database for application development teams or maintain production databases. The primary responsibility of a production DBA is to ensure the availability of production databases. They monitor the database, take care of upgrades and patches, allocate storage, perform backup and recovery, etc. A development DBA, on the other hand, works closely with the application development team and helps them come up with data model design, converts a logical data model into a physical database schema, estimates storage requirements, etc.

To bring database work and application development work into one single delivery pipeline, it is almost necessary that the development DBA be a part of the development team. Full-stack developers in the development team with good knowledge of the database may also wear the hat of a development DBA.

Database as Code

It is not feasible to have database changes and application code integrated into a single delivery pipeline unless database changes are treated the same way as application code. This necessitates scripting every change in the database and having them version-controlled. It should then be possible to stand up a new instance of the database automatically from the scripts on demand.

If we had to capture database objects as code, we would first need to classify them and evaluate each one of those types to see if and how they need to be captured as script (code). Following is a broad classification of them:

Database Structure

This is basically the definition of how stored data will be structured in the database and is also known as a schema. These include table definitions, views, constraints, indexes, and types. The data dictionary may also be considered as a part of the database structure.

Stored Code

These are very similar to application code, except that they are stored in the database and are executed by the database engine. They include stored procedures, functions, packages, triggers, etc.

Reference Data

These are usually a set of permissible values that are referenced from other tables that store business data. Ideally, tables representing reference data have very few records and don’t change much over the life cycle of an application. They may change when some business process changes but don’t usually change during the normal course of business.

Application Data or Business Data

These are the data that the application records during the normal course of business. The main purpose of any database system is to store these data. The other three types of database objects exist only to support these data.

Out of the above four types of database objects, the first three can be and should be captured as scripts and stored in a version control system.

| Type | Example | Scripted (Stored like code?) |

|---|---|---|

|

Database Structure |

Schema Objects like Tables, Views, Constraints, Indexes, etc. |

Yes |

|

Stored Code |

Triggers, Procedures, Functions, Packages, etc. |

Yes |

|

Reference Data |

Codes, Lookup Tables, Static data, etc. |

Yes |

|

Business/Application Data |

Data generated from day-to-day business operations |

No |

Table 1: Depicts what types of database objects can be scripted and what types can’t be scripted

As shown in the table above, business data or application data are the only types that won’t be scripted or stored as code. All rollbacks, revisions, archival, etc., are handled by the database itself; however, there is one exception. When a schema change forces data migration - say, for example, populating a new column or moving data from a base table to a normalized table - that migration script should be treated as code and should follow the same life cycle as the schema change.

Let's take an example of a very simple data model to illustrate how scripts may be stored as code. This model is so simple and so often used in examples, that it may be considered the “Hello, World!” of data modeling.

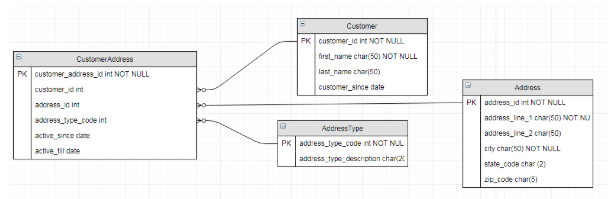

Figure 4: Example model with tables containing business data and ones containing reference data

In the model above, a customer may be associated with zero or more addresses, like billing address, shipping address, etc. The table AddressType stores the different types of addresses like billing, shipping, residential, work, etc. The data stored in AddressType can be considered reference data as they are not supposed to grow during day-to-day business operations. On the other hand, the other tables contain business data. As the business finds more and more customers, the other tables will continue to grow.

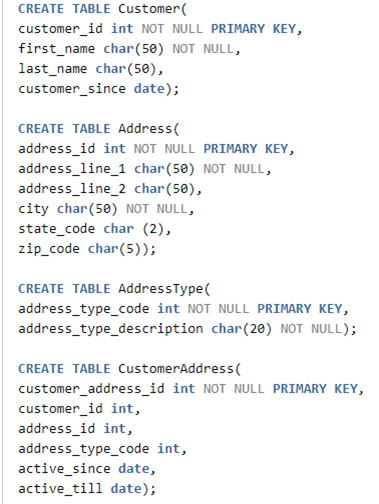

Example Scripts:

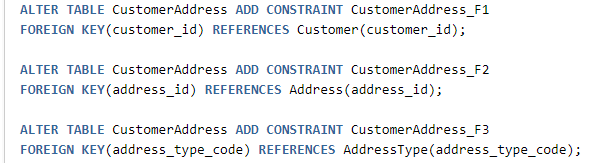

- Tables:

- Constraints:

- Reference Data:

We won’t get into any more details and cover each type of database object. The purpose of the examples is to illustrate that all database objects, except for business data, can be and should be captured in SQL scripts.

Version Control Database Artifacts in the Same Repository as Application Code

Keeping the database artifacts in the same repository of the version control system as the application code offers a lot of advantages. They can be tagged and released together since, in most cases, a change in database schema also involves a change in application code, and they together constitute a release. Having them together also reduces the possibility of application code and the database getting out of sync. Another advantage is just plain readability. It is easier for a new team member to come up to speed if everything related to a project is in a single place.

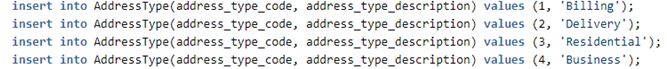

Figure 5: Example structure of a Java Maven project containing database code

Figure 5: Example structure of a Java Maven project containing database code

The above screenshot shows how database scripts can be stored alongside application code. Our example is a Java application, structured as a Maven project. The concept is however agnostic of what technology is used to build the application. Even if it was a Ruby or a .NET application, we would store the database objects as scripts alongside application code to let CI/CD automation tools find them in one place and perform necessary operations on them like building the schema from scratch or generating migration scripts for a production deployment.

Integrate Database Artifacts Into the Build Scripts

It is important to include database scripts in the build process to ensure that database changes go hand in hand with application code in the same delivery pipeline. Database artifacts are usually SQL scripts of some form and all major build tools support executing SQL scripts either natively or via plugins.

We won’t get into any specific build technology but will list down the tasks that the build would need to perform. Here we are talking about builds in local environments or CI servers. We will talk about builds in staging environments and production at a later stage.

The typical tasks involved are:

- Drop Schema

- Create Schema

- Create Database Structure (or schema objects): They include tables, constraints, indexes, sequences, and synonyms.

- Deploy stored code, like procedures, functions, packages, etc.

- Load reference data

- Load TEST data

If the build tool in question supports build phases, this will typically be in the phase before integration tests. This ensures that the database will be in a stable state with a known set of data loaded. There should be sufficient integration tests that will cause the build to fail if the application code goes out of sync with the data model. This ensures that the database is always integrated with the application code: the first step in achieving a Continuous Delivery model involving database change management.

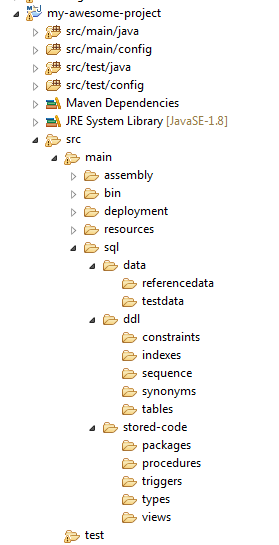

Figure 6: Screenshot of code snippet showing a Maven build for running database scripts

The above screenshot illustrates the usage of a Maven plugin to run SQL scripts. It drops the schema, recreates it, and runs all the DDL scripts to create tables, constraints, indexes, sequences, and synonyms. Then it deploys all the stored code into the database and finally loads all reference data and test data.

Refactor Data Model as Needed

Agile methodology encourages evolutionary design over upfront design; however, many organizations that claim to be Agile shops, actually perform an upfront design when it comes to data modeling. There is a perception that schema changes are difficult to implement later in the game, and thus it is important to get it right the first time. If the recommendations made in the previous sections are made, like having an integrated team with developers and DBAs, scripting database changes, and version controlling them alongside application code, it won’t be difficult to automate all schema changes. Once the deployment and rollback of database changes are fully automated and there is a suite of automated tests in place, it should be easy to mitigate risks in refactoring schema.

Avoid Shared Database

Having a database schema shared by more than one application is a bad idea, but they still exist. There is even a mention of a “Shared Database” as an integration pattern in a famous book on enterprise integration patterns, Enterprise Integration Patterns by Gregor Holpe and Bobby Woolf.

Any effort to bring application code and database changes under the same delivery pipeline won’t work unless the database truly belongs to the application and is not shared by other applications. However, this is not the only reason why a shared database should be avoided. "Shared Database" also causes tight coupling between applications and a multitude of other problems.

Dedicated Schema for Every Committer and CI Server

Developers should be able to work on their own sandboxes without the fear of breaking anything in a common environment like the development database instance; similarly, there should be a dedicated sandbox for the CI server as well. This follows the pattern of how application code is developed. A developer makes changes and runs the build locally, and if the build succeeds and all the tests pass, (s)he commits the changes.

The sandbox could be either an independent database instance, typically installed locally on the developer’s machine, or it could be a different schema in a shared database instance.

Figure 7: Developers make changes in their local environment and commit frequently

As shown in the above diagram, each developer has their own copy of the schema. When a full build is performed, in addition to building the application, it also builds the database schema from scratch. It drops the schema, recreates it, and executes DDL scripts to load all schema objects like tables, views, sequences, constraints, and indexes. It creates objects representing stored code, like functions, procedures, packages, and triggers. Finally, it loads all the reference data and test data. Automated tests ensure that the application code and database object are always in sync. It must be noted that data model changes are less frequent than application code, so the build script should have the option to skip the database build for the sake of build performance.

The CI build job should also be set up to have its own sandbox of the database. The build script performs a full build that includes building the application as well as building the database schema from scratch. It runs a suite of automated tests to ensure that the application itself and the database that it interacts with, are in sync.

Figure 8: Revised CI process with integration of database build with build of application code

Please note that the similarity of the process described in the above diagram with the one described in Figure 1. The build machine or the CI server contains a build job that is triggered by any commit to the repository. The build that it performs includes both the application build and the database build. The database scripts are now always integrated, just like application code.

Dealing With Migrations

The process described above would build the database schema objects, stored code, reference data, and test data from scratch. This is all good for continuous integration and local environments. This process won’t work for the production database and even QA or UAT environments. The real purpose of any database is storing business data, and every other database object exists only to support business data. Dropping schema and recreating it from scripts is not an option for a database currently running business transactions. In this case, there is a need for scripting deltas, i.e., the changes that will transition the database structure from a known state (a particular release of software) to a desired state. The transition will also include any data migration. Schema changes may lead to a requirement to migrate data as well. For example, as a result of normalization, data from one table may need to be migrated to one or more child tables. In such cases, a script that transforms data from the parent table to the children should also be a part of the migration scripts. Schema changes may be scripted and maintained in the source code repository so that they are part of the build. These scripts may be hand-coded during active development, but there are tools available to automate that process as well. One such tool is Flyway, which can generate migration scripts for the transition of one state of schema to another state.

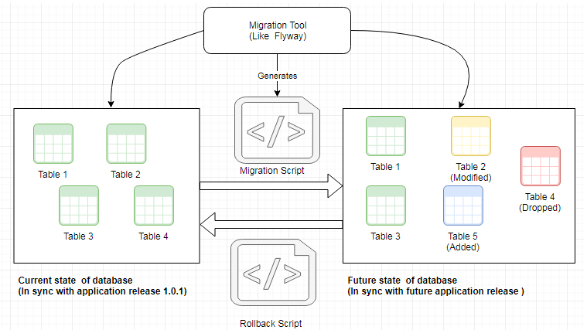

Figure 9: Automation of schema migrations and rollback

In the above picture, the left-hand side shows the current state of the database which is in sync with the application release 1.0.1 (the previous release). The right-hand side shows the desired state of the database in the next release. We have the state on the left-hand side captured and tagged in the version control system. The right-hand side is also captured in the version control system as the baseline, master branch, or trunk. The difference between the right-hand side and the left-hand side is what needs to be applied to the database in the staging environments and the production environment. The differences may be manually tracked and scripted, which is laborious and error-prone. The above diagram illustrates that tools like Flyway can automate the creation of such differences in the form of migration scripts. The automated process will create the following:

- Migration script (to transition the database from the prior release to the new release)

- Rollback script (to transition the database back to the previous release).

The generated scripts will be tagged and stored with other deploy artifacts. This automation process may be integrated with the Continuous Delivery process to ensure repeatable, reliable, and reversible (ability to rollback) database changes.

Continuous Delivery With Database Changes Incorporated Into It

Let us now put the pieces together. There is a Continuous Integration process already in place that rebuilds the database along with the application code. We have a process in place that generates migration scripts for the database. These generated migration scripts are a part of the deployment artifacts. The DevOps tools will use these released artifacts to build any of the staging environments or the production environment. The deployment artifacts will also contain rollback scripts to support self-service rollback. If anything goes wrong, the previous version of the application may then be redeployed and the database rollback script shall be run to transition the database schema to the previous state that is in sync with the previous release of the application code.

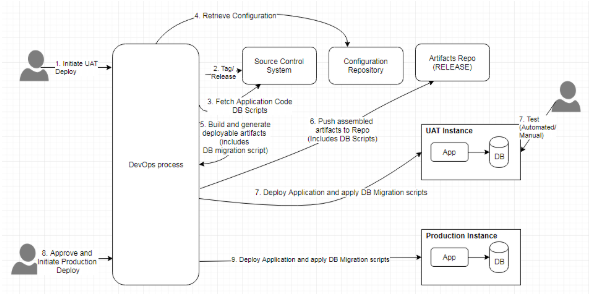

Figure 10: Continuous Delivery incorporating database changes

The above diagram depicts a Continuous Delivery process that has database change management incorporated into it. This assumes that a Continuous Integration process is already there in place. When a UAT (or any other staging environment like TEST, QA, etc.) deployment is initiated, the automated processes take care of creating a tag in the source control repository, building application deployable artifacts from the tagged codebase, generating database migration scripts, assembling the artifacts and deploying. The deployment process includes the deployment of the application as well as applying migration scripts to the database. The same artifacts will be used to deploy the application to the production environment, following the approval process. A rollback would involve redeploying the previous release of the application and running the database rollback script.

Tools Available in the Market

The previous sections primarily describe how to achieve CI/CD in a project that involves database changes by following some processes but don’t particularly take into consideration any tools that help in achieving them. The above recommendations are independent of any particular tool. A homegrown solution can be developed using common automation tools like Maven or Gradle for build automation, Jenkins or TravisCI for Continuous Integration, and Chef or Puppet for configuration management; however, there are many tools available in the marketplace, that specifically deal with Database DevOps. Those tools may also be taken advantage of. Some examples are:

Conclusion

Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery processes offer tremendous benefits to organizations, like accelerated time to market, reliable releases, and overall higher-quality software. Database change management is traditionally cautious and slow. In many cases, database changes involve manual processes and often cause a bottleneck to the Continuous Delivery process. The processes and best practices mentioned in this article, along with available tools in the market, should hopefully eliminate this bottleneck and help to bring database changes into the same delivery pipeline as application code.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments