Commands and Operations in Git

Learn more about Git commands and operations in this tutorial.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For Free

Before we get started with commands and operations, let us first understand the primary motive of Git. The purpose of Git is to manage a project or a set of files as they change over time. Git stores this information in a data structure called a Git repository. The repository is the core of Git.

To be very clear, a Git repository is the directory where all of your project files and related metadata are stored. Git records the current state of the project by creating a tree graph from the index and is usually in the form of a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG).

Now that you have understood what Git aims to achieve, let us go ahead with the operations and commands.

Git Tutorial: Operations & Commands

Some of the basic operations in Git are:

- Initialize

- Add

- Commit

- Pull

- Push

Some advanced Git operations are:

- Branching

- Merging

- Rebasing

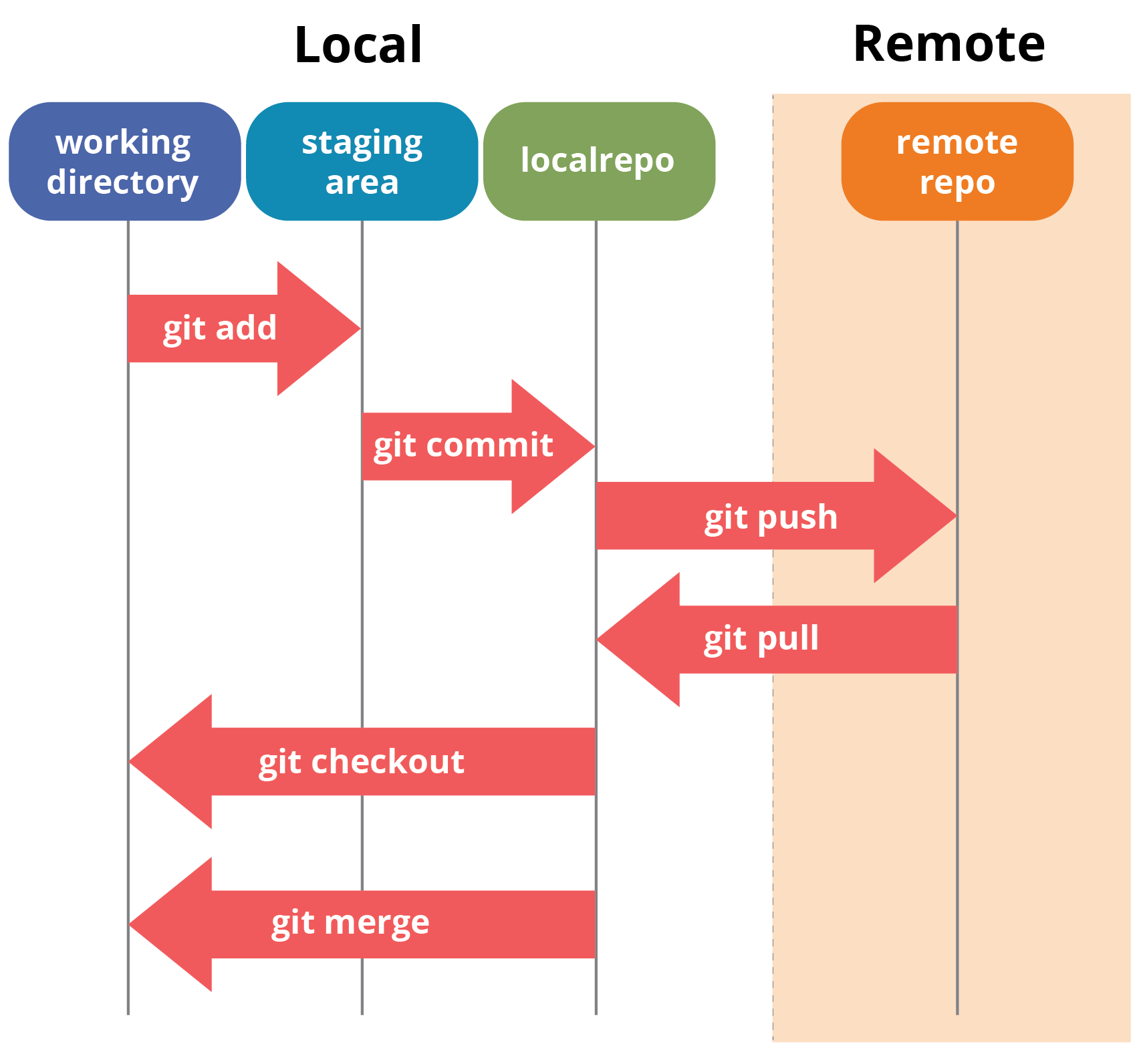

Let me first give you a brief idea about how these operations work within Git repositories. Take a look at the architecture of Git below:

If you don't understand the above diagram, you need not worry. I will be explaining these operations in detail during this Git tutorial. Let us begin with the basic operations.

You first need to install Git on your system.

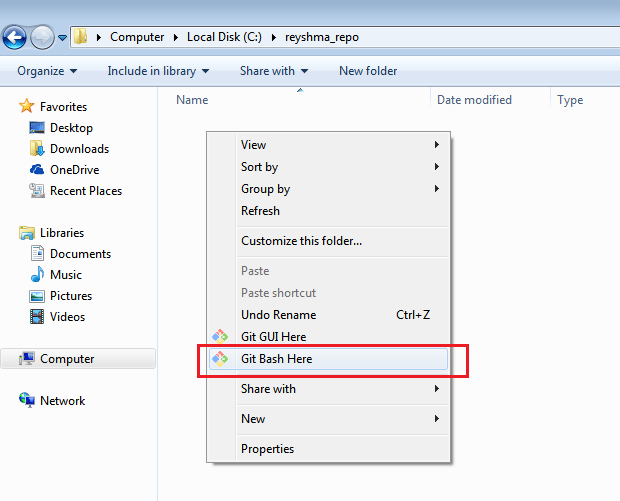

I will show you the commands and the operations using Git Bash. Git Bash is a text-only command-line interface for using Git on Windows and provides features to run automated scripts.

After installing Git in your Windows system, just open your folder/directory where you want to store all your project files; right-click and select ‘Git Bash Here’.

This will open up the Git Bash terminal where you can enter commands to perform various Git operations.

Now, the next task is to initialize your repository.

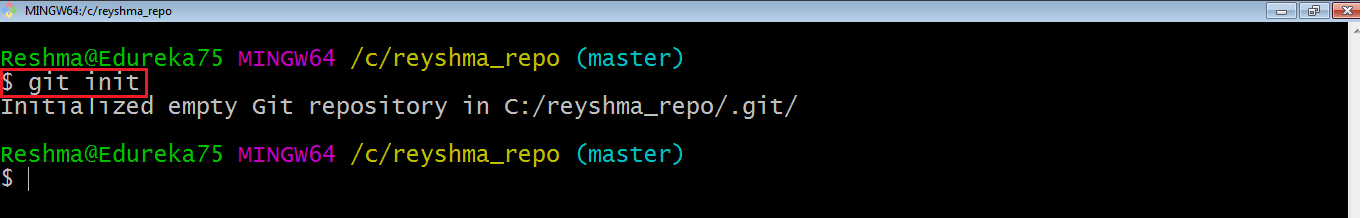

Initialize

In order to do that, we use the command git init.Please refer to the following screenshot.

git init creates an empty Git repository or re-initializes an existing one. It basically creates a .git directory with subdirectories and template files. Running a git init in an existing repository will not overwrite things that are already there. It rather picks up the newly added templates.

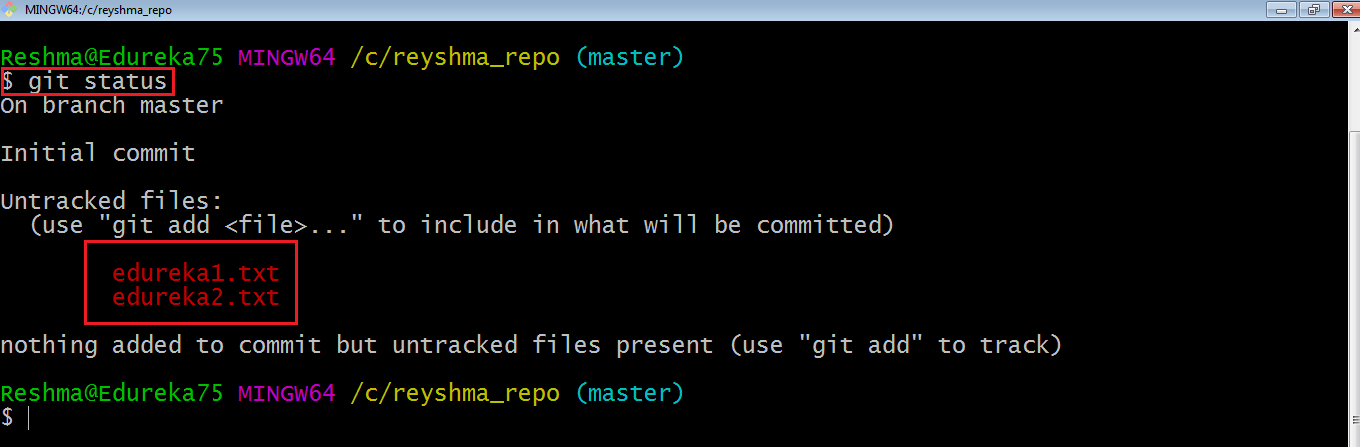

Now that my repository is initialized, let me create some files in the directory/repository. For e.g., I have created two text files namely edureka1.txt and edureka2.txt.

Let’s see if these files are in my index or not using the command git status. The index holds a snapshot of the content of the working tree/directory, and this snapshot is taken as the contents for the next change to be made in the local repository.

Git Status

The git status command lists all the modified files which are ready to be added to the local repository.

Let us type in the command to see what happens:

This shows that I have two files that are not added to the index yet. This means I cannot commit changes with these files unless I have added them explicitly in the index.

Add

This command updates the index using the current content found in the working tree and then prepares the content in the staging area for the next commit.

Thus, after making changes to the working tree, and before running the commit command, you must use the add command to add any new or modified files to the index. For that, use the commands below:

git add <directory>

or

git add <file>

Let me demonstrate the git add for you so that you can understand it better.

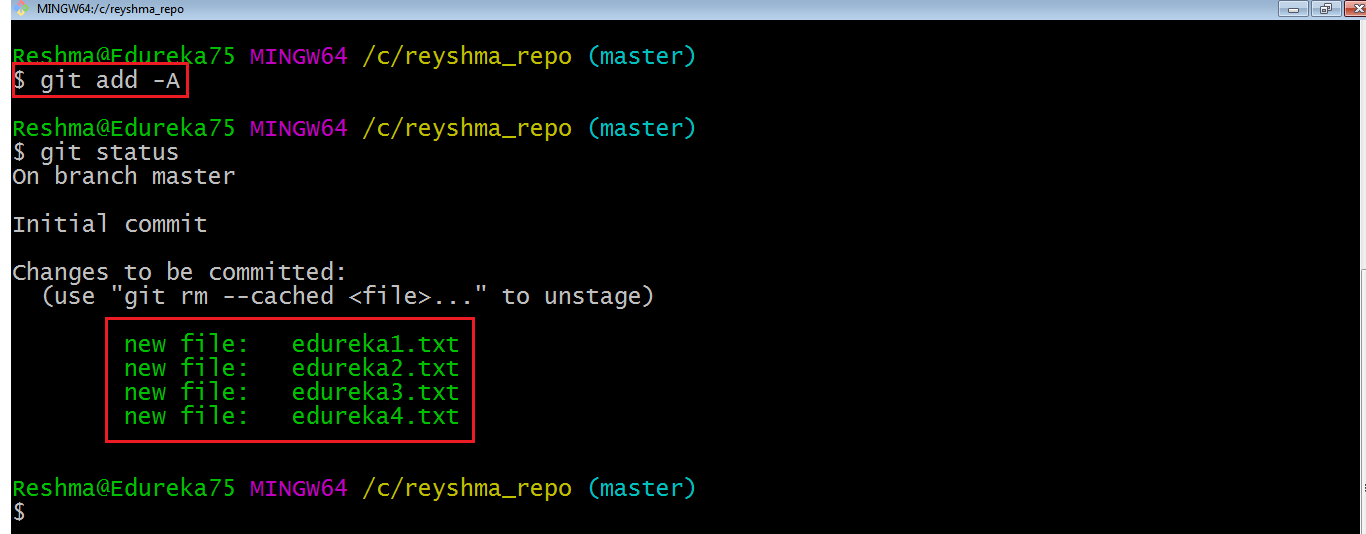

I have created two more files edureka3.txt and edureka4.txt. Let us add the files using the command git add -A. This command will add all the files to the index, which are in the directory but not updated in the index yet.

Now that the new files are added to the index, you are ready to commit them.

Commit

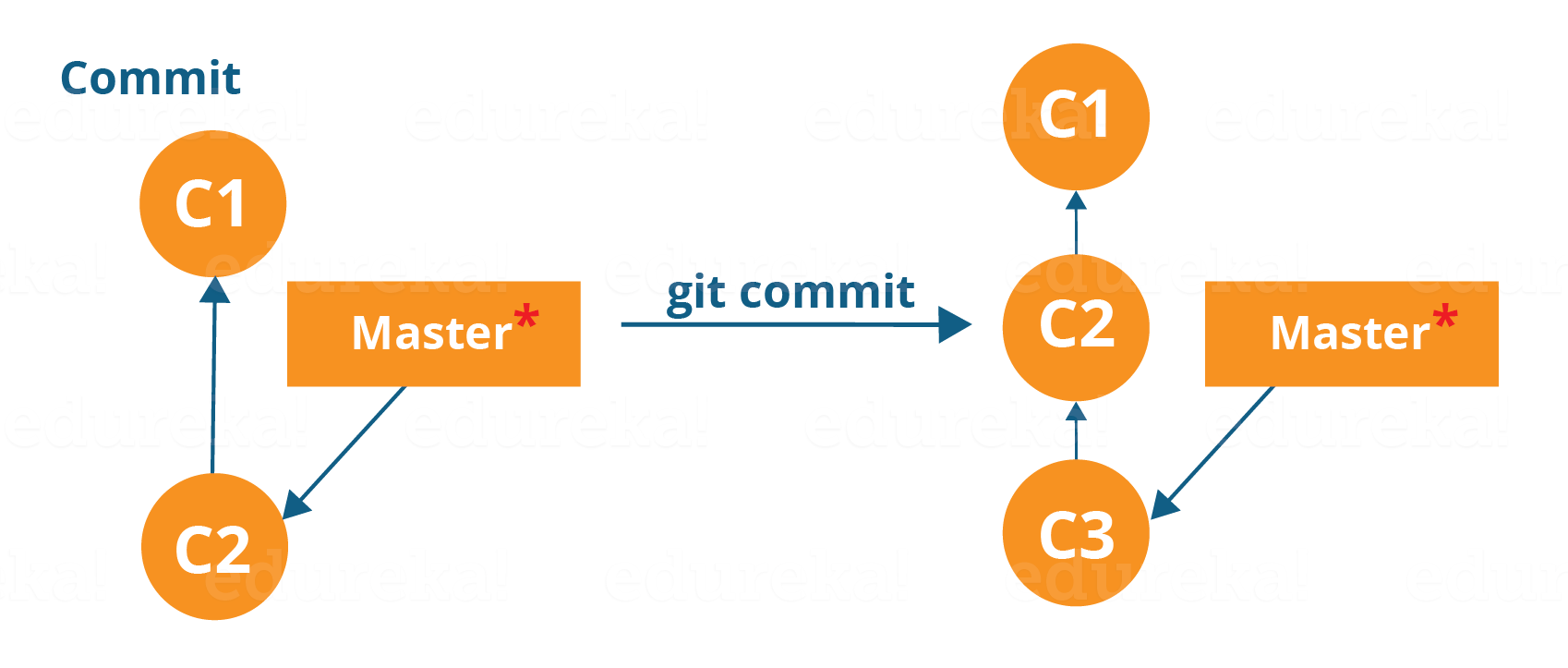

It refers to recording snapshots of the repository at a given time. Committed snapshots will never change unless done explicitly. Let me explain how commit works with the diagram below:

Here, C1 is the initial commit, i.e. the snapshot of the first change from which another snapshot is created with changes named C2. Note that the master points to the latest commit.

Now, when I commit again, another snapshot C3 is created and now the master points to C3 instead of C2.

Git aims to keep commits as lightweight as possible. So, it doesn’t blindly copy the entire directory every time you commit; it includes commit as a set of changes, or “delta” from one version of the repository to the other. In easy words, it only copies the changes made in the repository.

You can commit by using the command below:

git commit

This will commit the staged snapshot and will launch a text editor prompting you for a commit message.

Or you can use:

git commit -m “<message>”

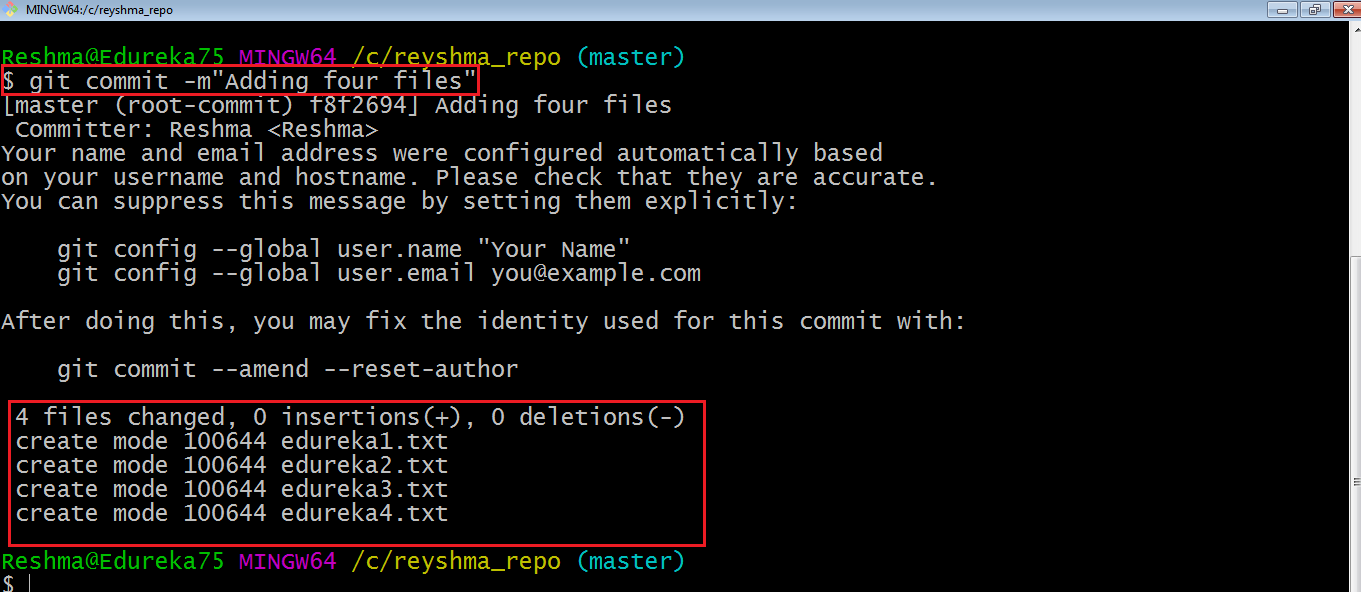

Let’s try it out.

As you can see above, the git commit command has committed the changes in the four files in the local repository.

Now, if you want to commit a snapshot of all the changes in the working directory at once, you can use the command below:

git commit -a

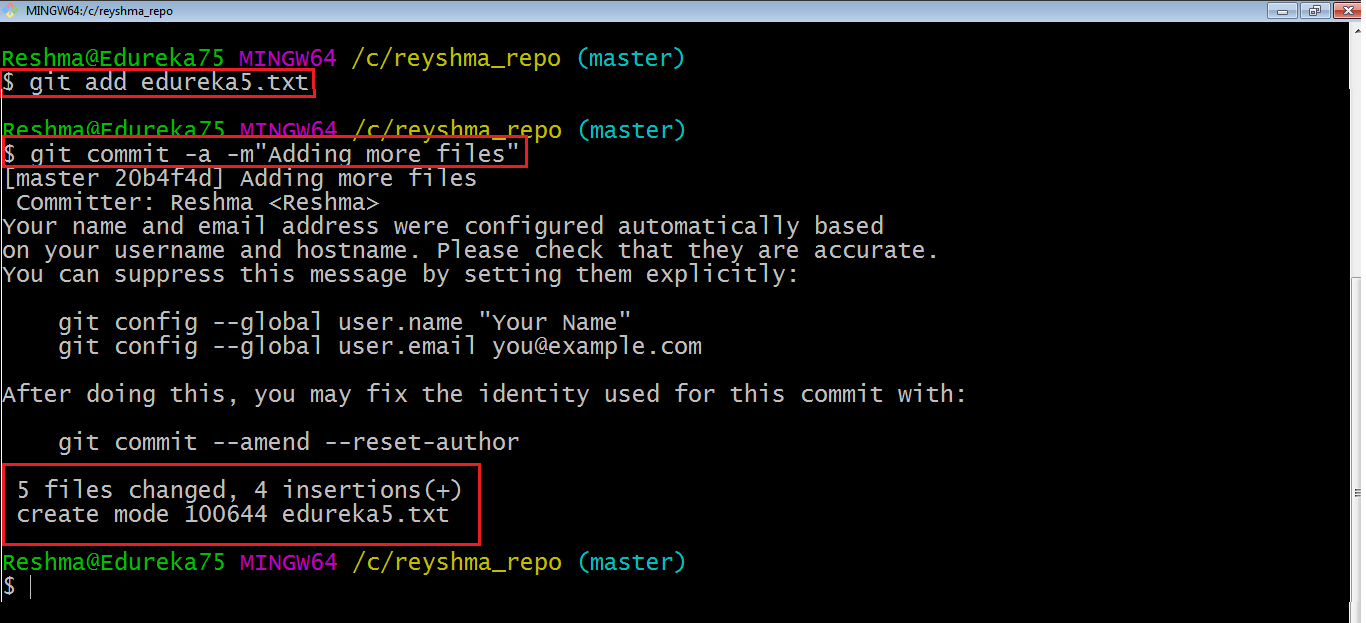

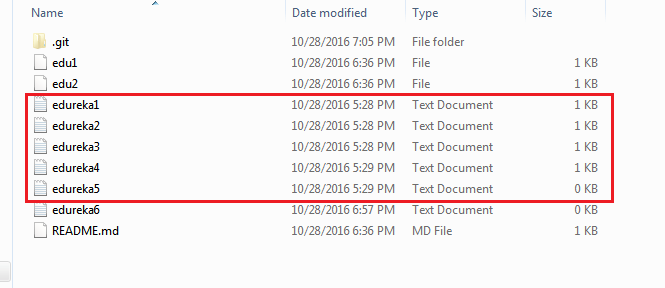

I have created two more text files in my working directory viz. edureka5.txt and edureka6.txt, but they are not added to the index yet.

I am adding edureka5.txt using the command:

git add edureka5.txt

I have added edureka5.txt to the index explicitly, but not edureka6.txt, and made changes in the previous files. I want to commit all changes in the directory at once. Refer to the snapshot below:

This command will commit a snapshot of all changes in the working directory but only includes modifications to tracked files, i.e. the files that have been added with git add at some point in their history. Hence, edureka6.txt was not committed because it was not added to the index yet. But changes in all previous files present in the repository were committed, i.e. edureka1.txt, edureka2.txt, edureka3.txt, edureka4.txt, and edureka5.txt.

Now, I have made my desired commits in my local repository.

Note that before you affect changes to the central repository, you should always pull changes from the central repository to your local repository to get updated with the work of all the collaborators that have been contributing to the central repository. For that, we will use the pull command.

Pull

The git pull command fetches changes from a remote repository to a local repository. It merges upstream changes in your local repository, which is a common task in Git-based collaborations.

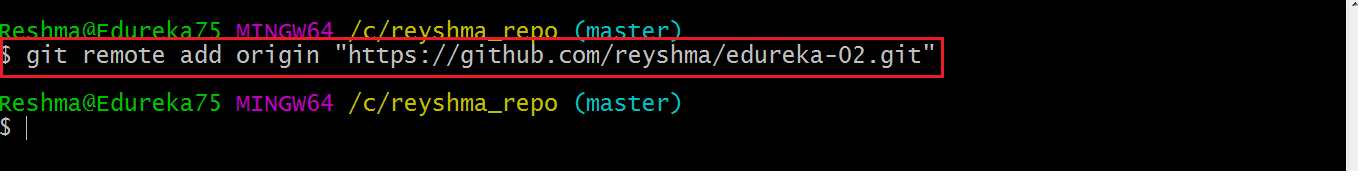

But first, you need to set your central repository as origin using the command:

git remote add origin <link of your central repository>

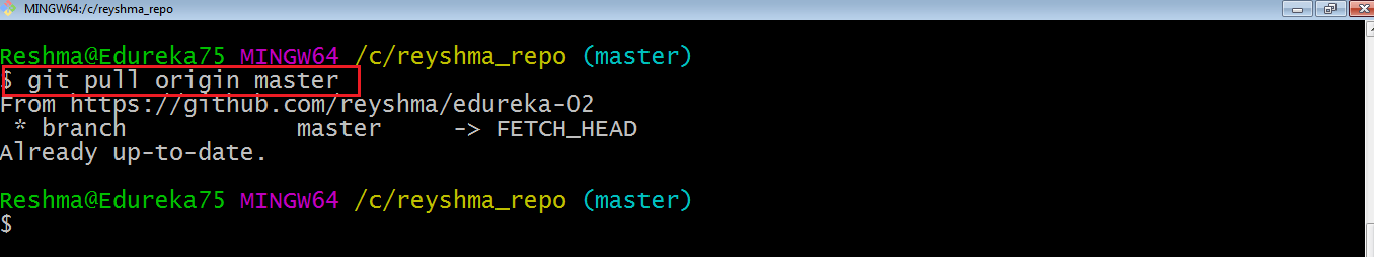

Now that my origin is set, let us extract files from the origin using pull. For that, use the command:

git pull origin master

This command will copy all the files from the master branch of the remote repository to your local repository.

Since my local repository was already updated with files from the master branch, hence the message is already up-to-date. Refer to the screenshot above.

Note: One can also try pulling files from a different branch using the following command:

git pull origin <branch-name>

Your local Git repository is now updated with all the recent changes. It is time you make changes in the central repository by using the push command

Push

This command transfer commits from your local repository to your remote repository. It is the opposite of the pull operation.

Pulling imports commits to local repositories whereas pushing exports commits to the remote repositories.

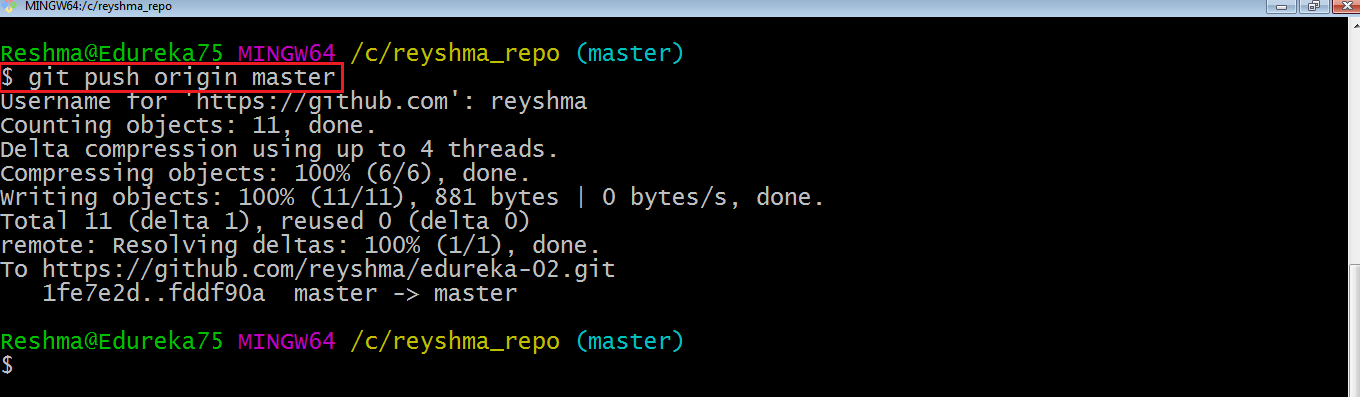

The use of git push is to publish your local changes to a central repository. After you’ve accumulated several local commits and are ready to share them with the rest of the team, you can then push them to the central repository by using the following command:

git push <remote>

Note: This remote refers to the remote repository which had been set before using the pull command.

This pushes the changes from the local repository to the remote repository along with all the necessary commits and internal objects. This creates a local branch in the destination repository.

Let me demonstrate it to you.

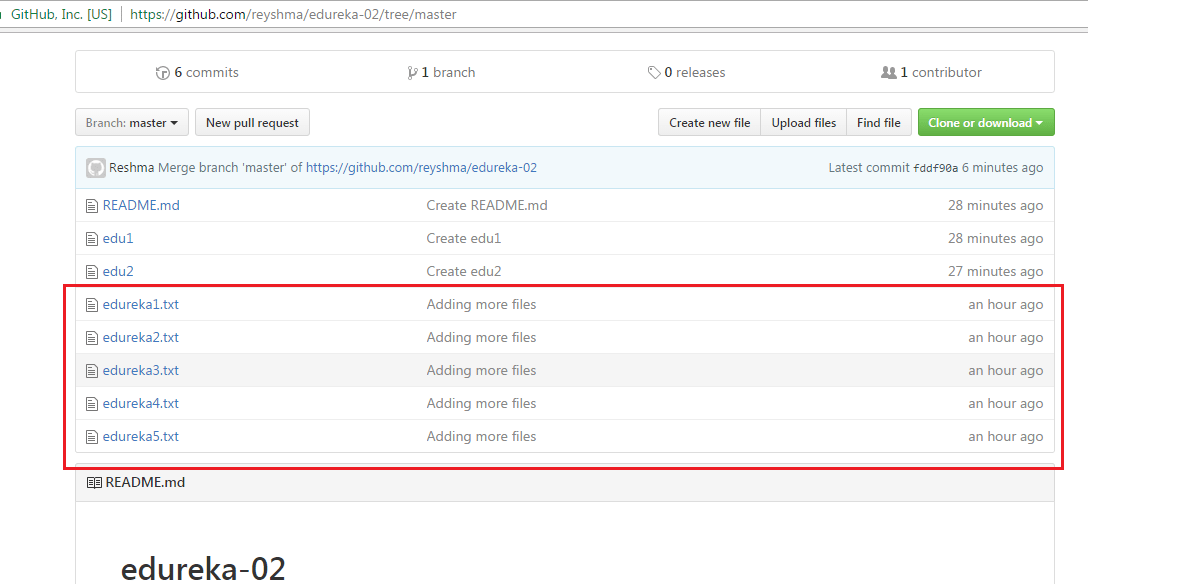

The above files are the files which we have already committed previously in the commit section and they are all “push-ready“. I will use the command git push origin master to reflect these files in the master branch of my central repository.

Let us now check if the changes took place in my central repository.

Yes, it did!

To prevent overwriting, Git does not allow push when it results in a non-fast forward merge in the destination repository.

Note: A non-fast forward merge means an upstream merge i.e. merging with an ancestor or parent branches from a child branch.

To enable such merge, use the command below:

git push <remote> –force

The above command forces the push operation even if it results in a non-fast forward merge.

At this point, I hope you have a good understanding of basic Git commands. Now, let’s take it a step further and learn how to branch and merge in Git.

Branching

Branches in Git are nothing but pointers to a specific commit. Git generally prefers to keep its branches as lightweight as possible.

There are basically two types of branches viz. local branches and remote-tracking branches.

A local branch is just another path of your working tree. On the other hand, remote-tracking branches have special purposes. Some of them are:

- They link your work from the local repository to the work on the central repository.

- They automatically detect which remote branches to get changes from when you use

git pull.

You can check what your current branch is by using the command:

git branch

The one mantra that you should always be chanting while branching is “branch early, and branch often”

To create a new branch, we use the following command:

git branch <branch-name>

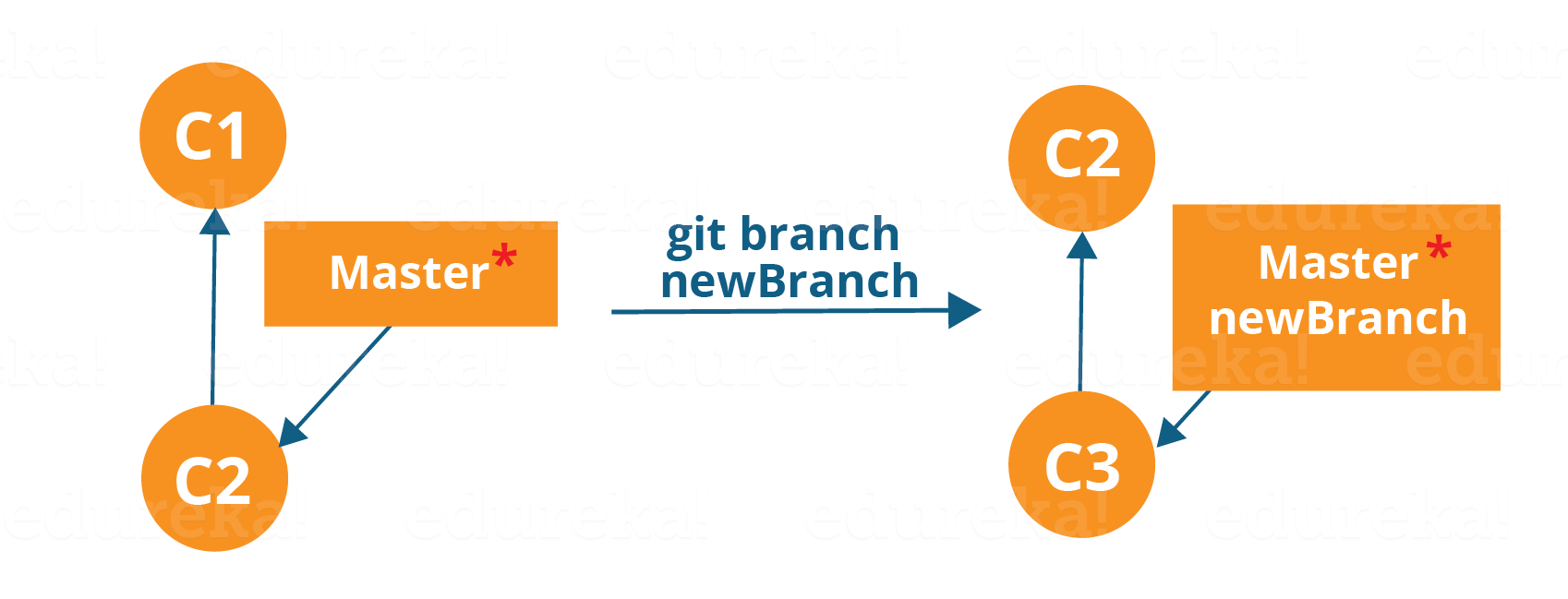

The diagram above shows the workflow when a new branch is created. When we create a new branch, it originates from the master branch itself.

Since there is no storage/memory overhead with making many branches, it is easier to logically divide up your work rather than have big chunky branches.

Now, let us see how to commit using branches.

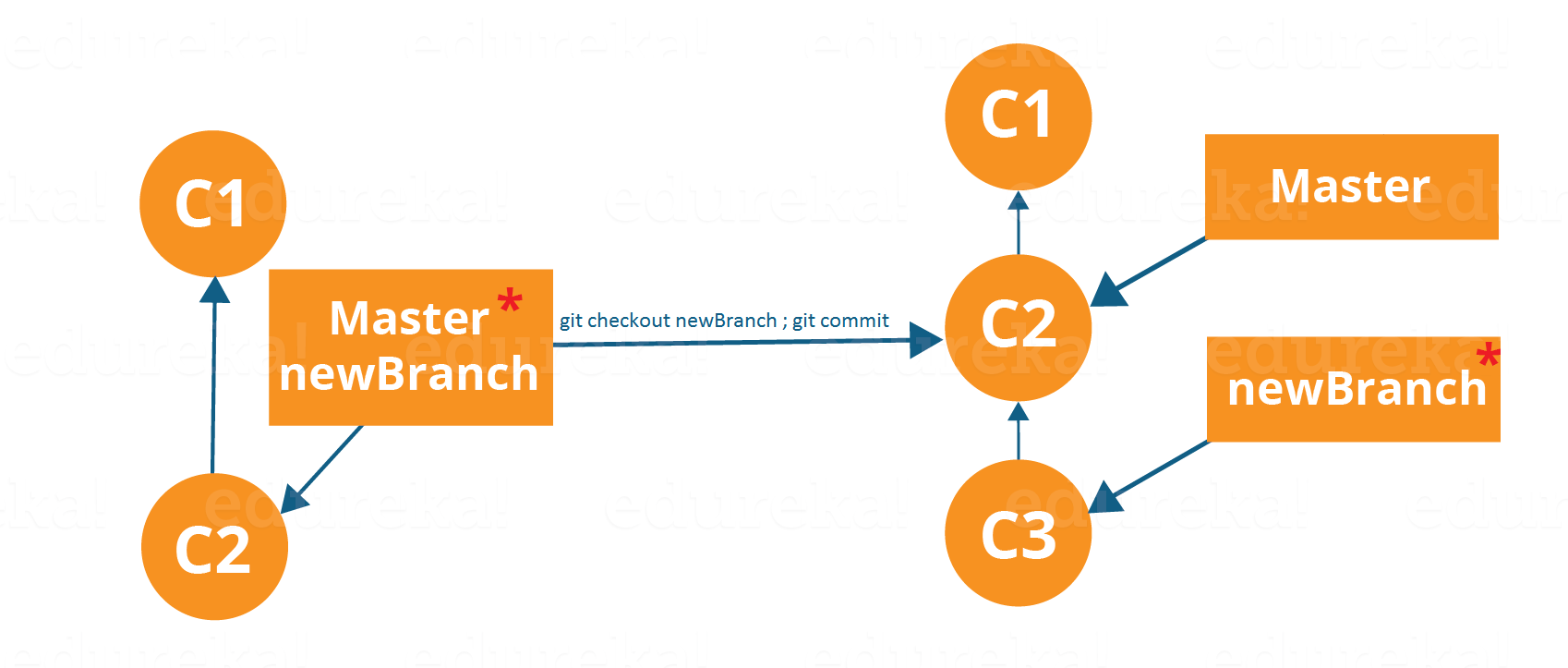

Branching includes the work of a particular commit along with all parent commits. As you can see in the diagram above, the newBranch has detached itself from the master and hence will create a different path.

Use the command below:

git checkout <branch_name> and then

git commit

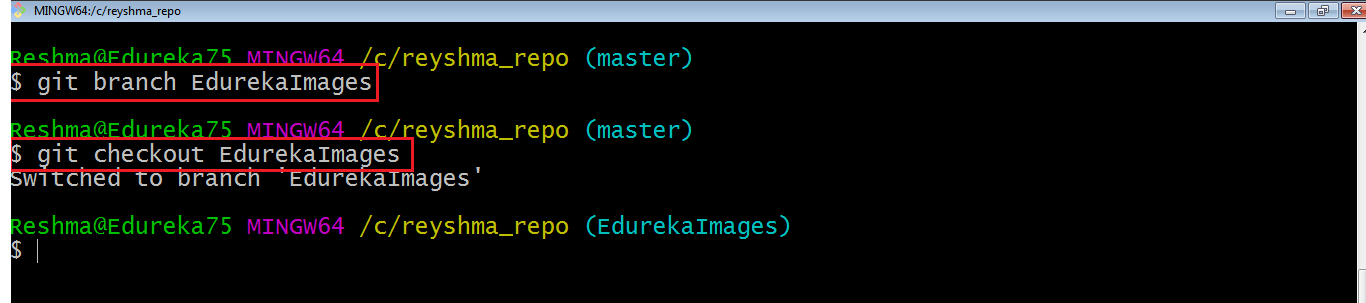

Here, I have created a new branch named “EdurekaImages” and switched on to the new branch using the command git checkout.

One shortcut to the above commands is:

git checkout -b[ branch_name]

This command will create a new branch and check out the new branch at the same time.

Now while we are in the branch EdurekaImages, add and commit the text file edureka6.txt using the following commands:

git add edureka6.txt

git commit -m” adding edureka6.txt”

Merging

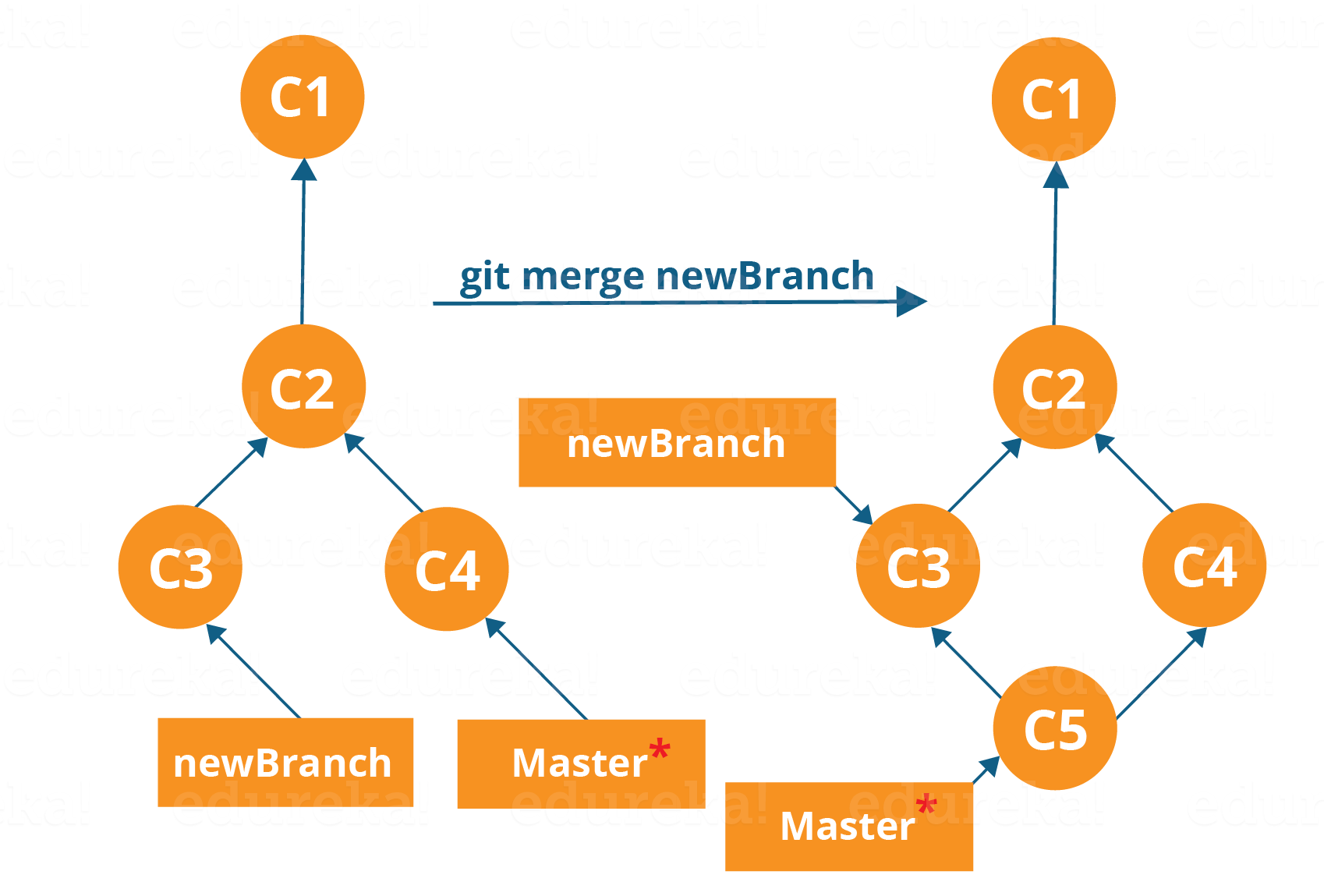

Merging is the way to combine the work of different branches together. This will allow us to branch off, develop a new feature, and then combine it back in.

The diagram above shows us two different branches-> newBranch and master. Now, when we merge the work of newBranch into master, it creates a new commit that contains all the work of master and newBranch.

Now, let us merge the two branches with the command below:

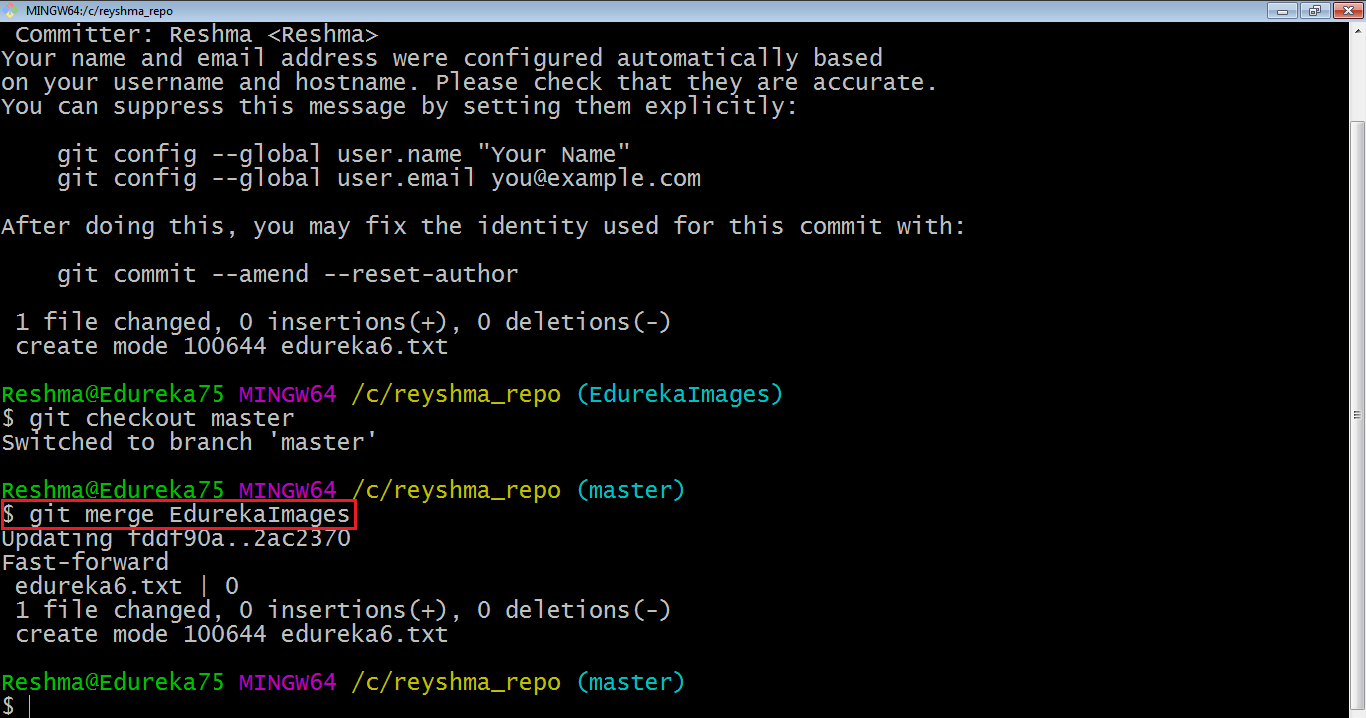

git merge <branch_name>

It is important to know that the branch name in the above command should be the branch you want to merge into the branch you are currently checking out. So, make sure that you are checked out in the destination branch.

Now, let us merge all of the work of the branch EdurekaImages into the master branch. For that, I will first check out the master branch with the command git checkout master and merge EdurekaImages with the command git merge EdurekaImages.

As you can see above, all the data from the branch name are merged to the master branch. Now, the text file edureka6.txt has been added to the master branch.

Merging in Git creates a special commit that has two unique parents.

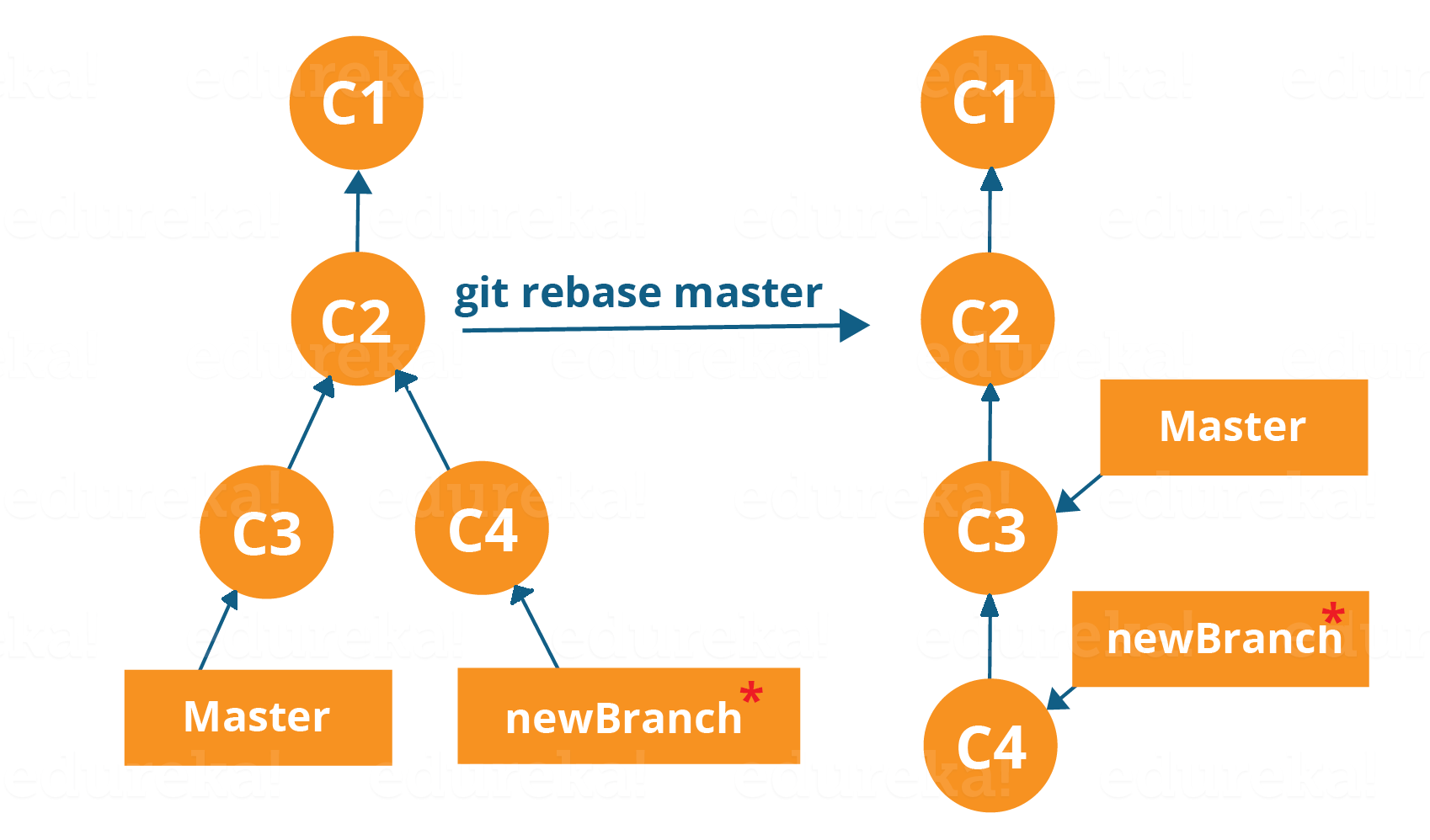

Rebasing

This is also a way of combining the work between different branches. Rebasing takes a set of commits, copies them, and stores them outside your repository.

The advantage of rebasing is that it can be used to make a linear sequence of commits. The commit log or history of the repository stays clean if rebasing is done.

Let us see how it happens.

Now, our work from newBranch is placed right after master and we have a nice linear sequence of commits.

Note: Rebasing also prevents upstream merges, meaning you cannot place master right after newBranch.

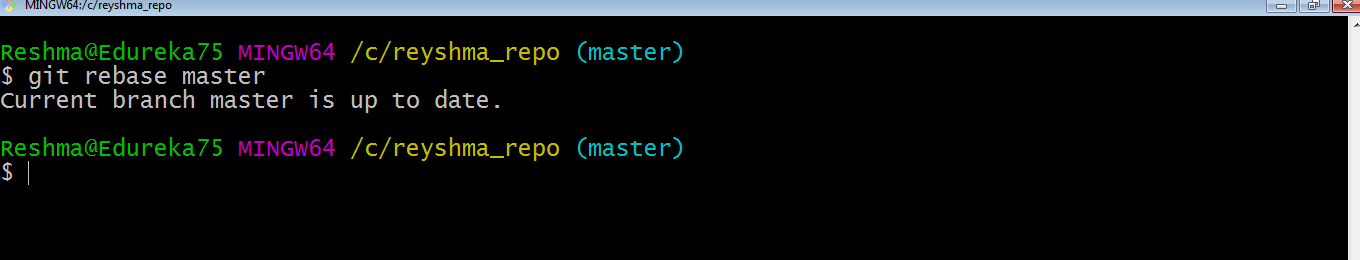

Now, to rebase master, type the command below in your Git Bash:

git rebase master

This command will move all our work from the current branch to the master. They look like as if they are developed sequentially, but they are developed parallelly.

Tips & Tricks

Now that you have gone through all the operations in Git, here are some tips and tricks you ought to know.

Archive Your Repository

Use the following command:

git archive master –format=zip –output= ../name-of-file.zip

It stores all files and data in a zip file rather than the .git directory.

Note that this creates only a single snapshot omitting version control completely. This comes in handy when you want to send the files to a client for review who doesn’t have Git installed on their computer.

Bundle Your Repository

It turns a repository into a single file.

Use the following command-

git bundle create ../repo.bundler master

This pushes the master branch to a remote branch only contained in a file instead of a repository.

An alternate way to do it is:

cd..

git clone repo.bundle repo-copy -b master

cd repo-copy

git log

cd.. /my-git-repo

Stash Uncommitted Changes

When we want to undo adding a feature or any kind of added data temporarily, we can “stash” them temporarily.

Use the commands below:

git status

git stash

git status

And when you want to re-apply the changes you “stash”ed , use the command below:

git stash apply

That's it, folks! I hope you have enjoyed this Git tutorial and learned the commands and operations along the way!

Further Reading

Published at DZone with permission of Arvind Phulare. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments