Data Lake Governance Best Practices

Without best practices, storage can become unmaintainable. Automating data quality, lifecycle, and privacy provide ongoing cleansing/movement of the data in your lake.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeData Lakes are emerging as an increasingly viable solution for extracting value from Big Data at the enterprise level, and represent the logical next step for early adopters and newcomers alike. The flexibility, agility, and security of having structured, unstructured, and historical data readily available in segregated logical zones brings a bevy of transformational capabilities to businesses. What many potential users fail to understand, however, is what defines a usable Data Lake. Often, those new to Big Data, and even well-versed Hadoop veterans, will attempt to stand up a few clusters and piece them together with different scripts, tools, and third-party vendors; this is neither cost-effective nor sustainable. In this article, we’ll describe how a Data Lake is much more than a few servers cobbled together: it takes planning, discipline, and governance to make an effective Data Lake.

Zones

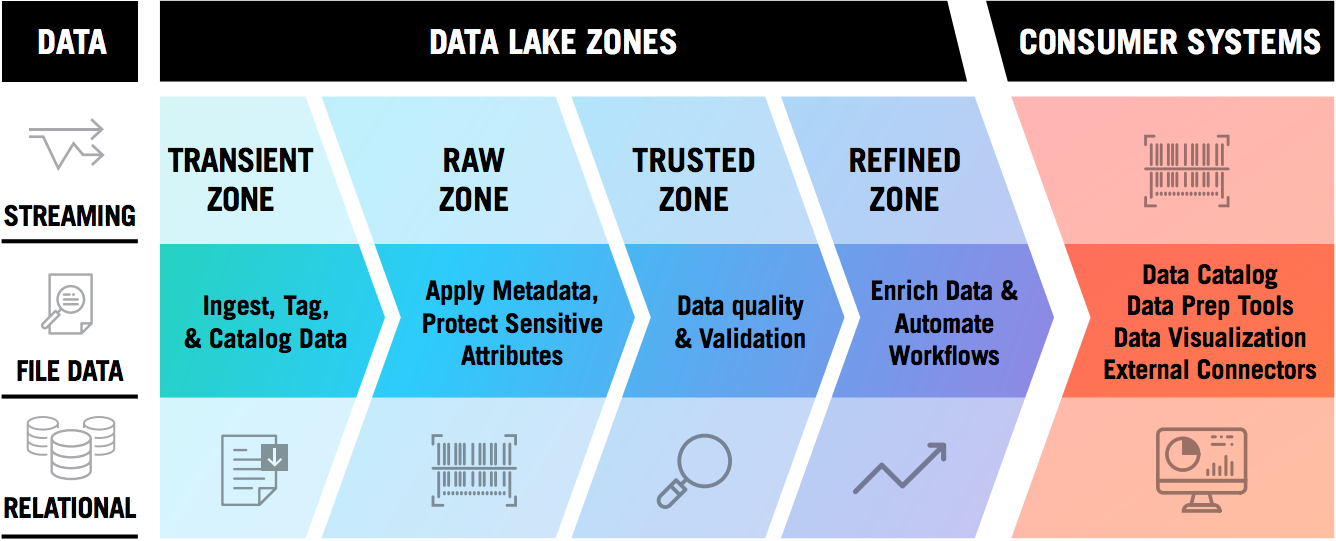

Within a Data Lake, zones allow the logical and/or physical separation of data that keeps the environment secure, organized, and Agile. Typically, the use of 3 or 4 zones is encouraged, but fewer or more may be leveraged. A generic 4-zone system might include the following:

Transient Zone — Used to hold ephemeral data, such as temporary copies, streaming spools, or other short-lived data before being ingested.

Raw Zone – The zone in which raw data will be maintained. This is also the zone where sensitive data must be encrypted, tokenized, or otherwise secured.

Trusted Zone – After Data Quality, Validation, or other processing is performed on data in the Raw Zone, it becomes the “source of truth” in this zone for downstream systems.

Refined Zone – Manipulated and enriched data is kept in this zone. This is used to store the output from tools like Hive or external tools that will write into to the Data Lake.

This arrangement can be adapted to the size, maturity, and unique use cases of the business as necessary, but will leverage physical separation via exclusive servers/clusters, logical separation through the deliberate structuring of directories and access privileges, or some combination of both. Visually, this architecture is similar to the one below.

Establishing and maintaining well-defined zones is the most important activity to create a healthy Lake, and promotes the rest of the concepts in this article. At the same time, it is important to understand what zones do not provide—namely, zones are not a Disaster Recovery or Data Redundancy policy.Although zones may be considered in DR, it’s still important to invest in a solid underlying infrastructure to ensure redundancy and resilience.

Lineage

As new data sources are added, and existing data sources updated or modified, maintaining a record of the relationships within and between datasets becomes more important. These relationships might be as simple as a renaming of a column, or as complex as joining multiple tables from different sources, each of which might have several upstream transformations themselves. In this context, lineage helps to provide both traceability to understand where a field or dataset originates and an audit trail to understand where, when, and why a change was made. This may sound simple, but capturing details about data as it moves through the Lake is exceedingly hard, even with some of the purpose-built software being deployed today. The entire process of tracking lineage involves aggregating logs at both a transactional level (who accessed the data and what did they do?) and at a structural or filesystem level (what are the relationships between datasets and fields?). In the context of the Data Lake, this will include any batch and streaming tools that touch the data (such as MapReduce and Spark), but also any external systems that may manipulate the data, such as RDBMS systems. This is a daunting task, but even a partial lineage graph can fill the gaps of traditional systems, especially as new regulations such as GDPR emerge; flexibility and extensibility are key to manage future change.

Data Quality

In a Data Lake, all data is welcome, but not all data is equal. Therefore, it is critical to define the source of the data and how it will be managed and consumed. Stringent cleansing and data quality rules might need to be applied to data that requires regulatory compliance, heavy end-user consumption, or auditability. On the other hand, not much value can be gained by cleansing social media data or data coming from various IoT devices. One can also make a case to consider applying the data quality checks on the consumption side rather than on the acquisition side. Hence, a single Data Quality architecture might not apply for all types of data. One has to be mindful of the fact that the results used for analytics could have an impact if the data is ‘cleansed.’ A field-level data quality rule that fixes values in the datasets can sway the outcomes of predictive models as those fixes can impact the outliers. Data quality rules to measure the usability of the dataset by comparing the ‘expected vs. received size of the dataset’ or ‘NULL Value Threshold’ might be more suitable in such scenarios. Often the level of required validation is influenced by legacy restrictions or internal processes that already are in place, so it’s a good idea to evaluate your company’s existing processes before setting new rules.

Privacy/Security

A key component of a healthy Data Lake is privacy and security, including topics such as role based access control, authentication, authorization, as well as encryption of data at rest and in motion. From a pure Data Lake and data management perspective the main topic tends to be data obfuscation including tokenization and masking of data. These two concepts should be used to help the data itself adhere to the security concept of least privilege. Restricting access to data also has legal implications for many businesses looking to comply with national and international regulations for their vertical. Restriction access takes several forms; the most obvious is the prodigious use of zones within the storage layer.In short, permissions in the storage layer can be configured such that access to the data in its most raw format is extremely limited. As that data is later transformed through tokenization and masking (i.e. hiding PII data) access to data in later zones can be expanded to larger groups of users.

DLM

Enterprises must work hard to develop the focus of their data management strategy to more effectively protect, preserve, and serve their digital assets. This involves investing in time and resources to fully create a lifecycle management strategy and to determine whether to use a flat structure or to leverage tiered protection. The traditional premise of a Data Lifecycle Management was based on the fact that data was created, utilized, and then archived. Today, this premise might hold true for some transactional data, but many data sources now remain active from a read perspective, either on a sustained basis or during semi-predictable intervals. Enterprises that know and understand the similarities and differences across their information, data and storage media, and are able to leverage this understanding to maximize usage of different storage tiers, can unlock value while removing complexity and costs.

Conclusion

Much like relational databases in the days of their infancy, some implementations of Hadoop in recent years have suffered from a lack of best practices. When considering using Hadoop as a Data Lake there are many best practices to consider. Utilizing zones and proper authorization as a part of a data workflow framework provides a highly scalable and parallel system for data transformation.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments