The Fire From Gods

Here, discover the fire of Prometheus and evaluate its use to observe systems enforcing the exposure of contextual metrics of the system's specific business.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeWarning: The following are notes I've taken during an analysis I made upon tools and methodologies for monitoring and observing distributed systems. After the work, I reviewed them to make them a little bit more discursive.

My primary goal was to evaluate the use of Prometheus to observe systems enforcing the exposure of contextual metrics of the system's specific business. For sure my goal was not to become an expert in configuring and deploying Prometheus, so don't be disappointed.

Some - if not most - of the concepts are well known, but I found it useful to write them to give the writing a self-consistent form.

Discover the Fire

As everyone knows, Prometheus is an open-source monitoring system originally built at SoundCloud and then entered into the Cloud Native Computing Foundation family.

Even if it carries with it the reputation of a time series database is a lot more:

It collects timestamped metrics optionally labeled.

It provides alerting rules and a ready-to-use integration with AlertMaganager to easily implement alerts and notifications.

However, more importantly:

It uses a pull rather than push approach for collecting.

It defined a metric format that became the de facto standard for monitoring systems (about this take a look at the OpenMetrics project).

It defined query language, PromQL, that even it became the de facto standard for the monitoring system.

Scraping

Prometheus scrapes targets, which means that as long as a system exposes metrics in Prometheus format, the only thing needed to collect data is to give Prometheus that endpoint.

Now it seems not so important and not so different from a push approach but actually, it makes a lot of difference:

In the container world, adding things (think about sidecars) without changing the application is a common job.

Even without containers, it is not so difficult (actually widely used) dynamically add things. Coming from Java, I'm thinking about Java agents.

It is easier to detect loss of signals: getting errors is easier to detect than the absence of something, which is what would happen in a push scenario.

There are a couple of drawbacks:

Every metric must be stored somewhere by the monitored system (even placing data in RAM is somehow storing data), so the availability of metrics depends on both monitored and monitoring system storage.

Metrics are available after some time the events happened in the monitored system. This is caused by the scrape interval.

Scraping is possible with systems that can act as servers (can respond to an HTTP request). Thinking about IoT devices became slightly difficult.

The Prometheus Exposition Format

Metrics are collected via HTTP request in text format as a sequence of lines and composed by:

- The name

- One or more labels thanks to which PromQL can filter or group

- The value in float64 format

Timestamps are added by Prometheus when receiving the data. That's why there is a discrepancy between metrics timestamps and the effective timing of events and the time stored.

This seems pretty obvious or slightly relevant for aggregated metrics (see histograms and summary), but could cause some trouble if you expect to gain a specific metric value for an exact time (maybe relying on other input like logs).

Metrics follow the pattern below:

<metric name>{<label name>=<label value>, ...} value

For example:

# HELP grafana_page_response_status_total page http response status

# TYPE grafana_page_response_status_total counter

grafana_page_response_status_total{code="200"} 210

grafana_page_response_status_total{code="404"} 0

grafana_page_response_status_total{code="500"} 0

grafana_page_response_status_total{code="unknown"} 4

- Everything after

#and until the line feed is a comment. grafana_page_response_status_totalis the metric name.- Everything that is inside the brackets represents labels made by keys and values. The example shows nicely the use of labels for aggregating (you can see 210 responses with

code="200"). - After the closing curly bracket separated by white space is the value.

From the HTTP point of view, it is nothing fancy: text/plain; version=0.0.4; charset=utf-8 as Content-Type and the list of metrics in the body.

This is an example of a request made with CURL to a Grafana pod running locally (yes, Grafana natively exposes metrics about itself in Prometheus format):

* Trying 10.100.224.149:3000...

* Connected to grafana.observe.svc.cluster.local (10.100.224.149) port 3000 (#0)

> GET /metrics HTTP/1.1

> Host: grafana.observe.svc.cluster.local:3000

> User-Agent: curl/7.84.0-DEV

> Accept: */*

>

* Mark bundle as not supporting multiuse

< HTTP/1.1 200 OK

< Cache-Control: no-cache

< Content-Type: text/plain; version=0.0.4; charset=utf-8

< Expires: -1

< Pragma: no-cache

< X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

< X-Frame-Options: deny

< X-Xss-Protection: 1; mode=block

< Date: Mon, 22 Aug 2022 10:35:05 GMT

< Transfer-Encoding: chunked

<

# HELP access_evaluation_duration Histogram for the runtime of evaluation function.

# TYPE access_evaluation_duration histogram

access_evaluation_duration_bucket{le="1e-05"} 0

access_evaluation_duration_bucket{le="4e-05"} 0

access_evaluation_duration_bucket{le="0.00016"} 0

access_evaluation_duration_bucket{le="0.00064"} 0

access_evaluation_duration_bucket{le="0.00256"} 0

access_evaluation_duration_bucket{le="0.01024"} 0

access_evaluation_duration_bucket{le="0.04096"} 0

access_evaluation_duration_bucket{le="0.16384"} 0

access_evaluation_duration_bucket{le="0.65536"} 0

access_evaluation_duration_bucket{le="2.62144"} 0

access_evaluation_duration_bucket{le="+Inf"} 0

access_evaluation_duration_sum 0

access_evaluation_duration_count 0

The Four Metrics Types

One thing I didn't believe at first but then I realized is that four metrics types can fit basically all the needs, even when defining custom metrics. Here they are.

Counter

The counter is something that always grows and never decreases unless restarted. It is useful for representing for example number of errors or requests served.

# HELP prometheus_http_requests_total Counter of HTTP requests.

# TYPE prometheus_http_requests_total counter

prometheus_http_requests_total{code="200",handler="/-/healthy"} 46

prometheus_http_requests_total{code="200",handler="/-/ready"} 48

prometheus_http_requests_total{code="200",handler="/-/reload"} 1

prometheus_http_requests_total{code="200",handler="/metrics"} 16

Most of the time counters are used with some PromQL aggregator function like rate to calculate averages, for example:

rate(prometheus_http_requests_total{code="200"}[5m])

This calculates the number of requests per second in the last 5 minutes.

By the way, sometimes this can be useful as an absolute value. For example, by having a job that executes tasks, exposing the number of completed tasks, and the number of total tasks, it is possible to monitor the overall progress of the job.

Gauge

When measures go up and down then it's time for gauges. They fit pretty well, for example, when measuring resource usage but sometimes are useful for metrics that look like counters:

- Concurrent requests

- Concurrent active users

- Server connection pool committed resources

# TYPE promhttp_metric_handler_requests_in_flight gauge

promhttp_metric_handler_requests_in_flight 1

Histogram

With histogram things became interesting. Instead of returning a single value during a scrape they return multiple items:

- The number of measurements is expressed as a counter and identified by the name of the metrics followed by the suffix

_count. - The sum of all values of all measurements is expressed as a counter and identified by the name of the metrics followed by the suffix

_sum. - A list of buckets distinguished by a label named

le(the bucket upper bound) that counts the number of measurements falling under that specific bound. These are identified by the name of the metrics followed by the suffix_bucket.

NOTE: One thing I found nice is that histograms are basically a set of counters that share the same name prefix and distinguish values with labels and name suffixes.

# HELP prometheus_http_request_duration_seconds Histogram of latencies for HTTP requests.

# TYPE prometheus_http_request_duration_seconds histogram

prometheus_http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{handler="/metrics",le="0.1"} 16

prometheus_http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{handler="/metrics",le="0.2"} 16

prometheus_http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{handler="/metrics",le="0.4"} 16

prometheus_http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{handler="/metrics",le="1"} 16

prometheus_http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{handler="/metrics",le="3"} 16

prometheus_http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{handler="/metrics",le="8"} 16

prometheus_http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{handler="/metrics",le="20"} 16

prometheus_http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{handler="/metrics",le="60"} 16

prometheus_http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{handler="/metrics",le="120"} 16

prometheus_http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{handler="/metrics",le="+Inf"} 16

prometheus_http_request_duration_seconds_sum{handler="/metrics"} 0.1199457

prometheus_http_request_duration_seconds_count{handler="/metrics"} 16

So using request duration as a metric how could this look like an implementation logic for the exposure?

Given that the upper bounds must be pre-defined and all values for le being known:

- Every time a request is served, its duration is evaluated to check under what bounds it falls.

- After the bounds are found, the respective counters are increased.

- The

_countis increased. - The duration is added to the

_sumcounter.

NOTE: One consequence of using inclusive upper bound as aggregation is that a measure can fall into more than a group. In the example above, 16 requests are being served, and all are within 0.1 seconds (the value of _sum confirms this since it is 0.1199457). Therefore, all buckets contain 16 items and all are equal to _count (typically at least one bucket is equal to _count and is +Inf).

Summary

While histograms define upper bounds, summaries define quantiles so measurements are distributed into buckets based upon distribution. Similarly to summaries, histograms return _sum and _count following the same rules, but the items:

- Do not provide specific suffix (like

_bucketfor histograms) - Measure the value of the specific quantile

# HELP go_gc_duration_seconds A summary of the pause duration of garbage collection cycles.

# TYPE go_gc_duration_seconds summary

go_gc_duration_seconds{quantile="0"} 9.66e-05

go_gc_duration_seconds{quantile="0.25"} 0.0001877

go_gc_duration_seconds{quantile="0.5"} 0.0001912

go_gc_duration_seconds{quantile="0.75"} 0.0002081

go_gc_duration_seconds{quantile="1"} 0.0015068

go_gc_duration_seconds_sum 0.0041706

go_gc_duration_seconds_count 13

Given the example above, we can say:

- The minimum value is 9.66e-05:

quantile="0". - The max value is 0.0015068:

quantile="1". - The median is 0.0001912:

quantile="0.5". quantile="0.25"andquantile="0.275represent respectively 25th and 75th percentile.

NOTE: One consequence of using quantile is that distribution can be calculated only after receiving all the measurements for the given period (1 second in the example above). Furthermore, the calculation must be done by the monitored system, so it is more expensive.

Turn on the Fire

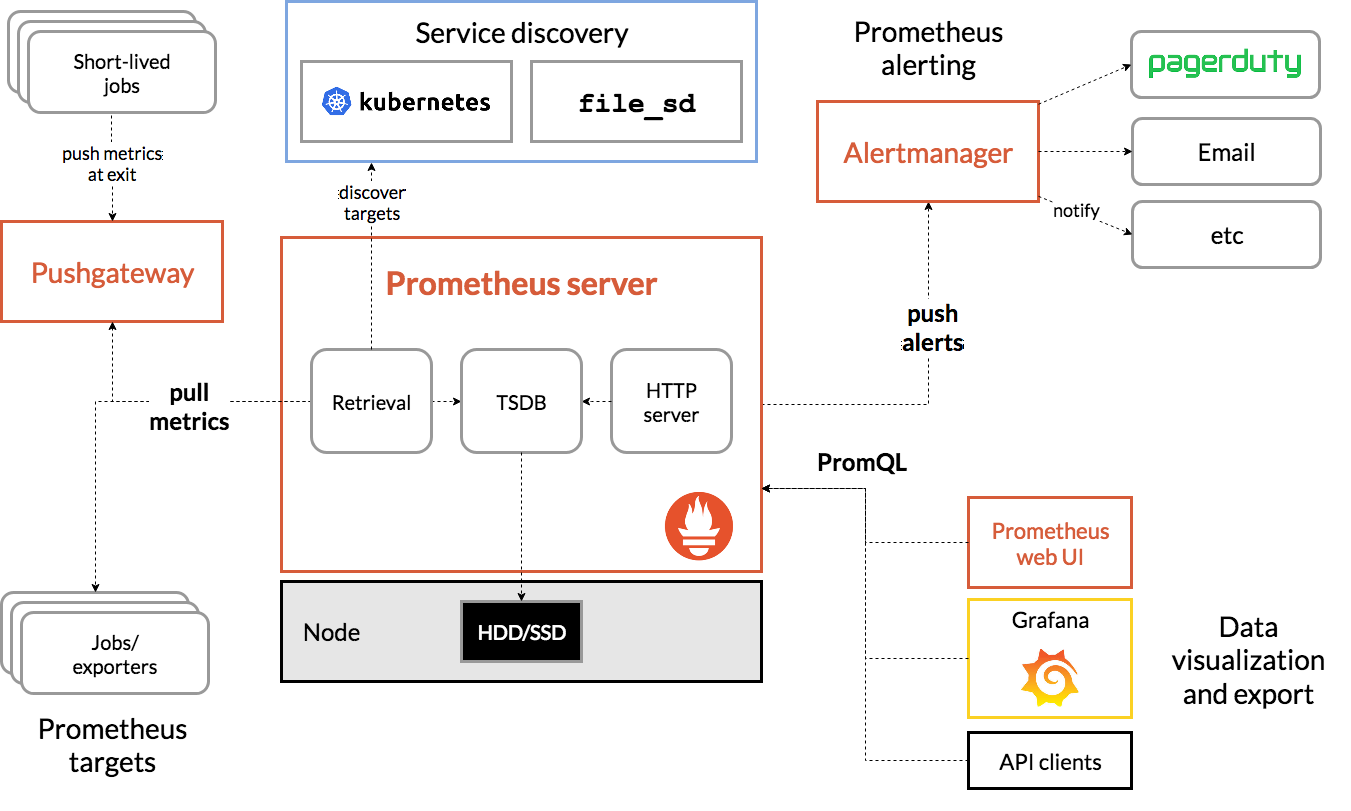

Now that Prometheus seems more familiar, what is missing is to make it run? Let's check its architecture:

The figure shows the Prometheus architecture directly taken from the Prometheus Overview

Putting aside Pushgateway (that allows systems to push metrics to somewhere Prometheus can pull inverting the approach) and Alertmanager (that handles alerts based on Prometheus rules integrating with notification services), the Prometheus server is standalone.

As stated on the FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS page:

The main Prometheus server runs standalone and has no external dependencies.

So no additional databases or other components are needed (at first).

NOTE: My goal is not to analyze how to fully and securely deploy Prometheus stack in a production environment so obviously this section cannot be considered exhaustive

The documentation proposes different installation options.

- Pre-compiled binaries

- From source

- Using Docker

- Using configuration management systems (Ansible, Chef, Puppet, and SaltStack)

Since my study is related to a Kubernetes environment, I picked Docker.

There are different options when evaluating the way to handle Kubernetes installation:

- Helm

- Kustomize

- Operator

- Just rely on standard Kubernetes resources

I decided to use the Prometheus Operator project.

It is beyond the scope of this writing to give a comparison between the different options, but the main reason for my choice is that I was searching for something as responsive as possible. The Operator seems to me the most suitable.

Spinoff

When talking about Operator in Kubernetes we talk about a pattern, not a tool. That's because everything that is needed already exists in vanilla Kubernetes: Custom Resources and Controllers.

Let's start by understanding the Resource. A Resource is an API that stores a collection of objects of a specific kind.

For example, executing an HTTP GET to https://{k8s-api}/apis/apps/v1/namespaces/kube-system/deployments will result in a list of deployments in the kube-system namespace, while executing an HTTP DELETE at https://{k8s-api}/api/v1/namespaces/default/pods/nginx will delete the specific nginx object.

TIPS: A quick way that I love to play with Kubernetes API is the joint use of the --v=8 flag and proxy command when using kubectl. The first change the log level so that the endpoints called by kubectl are shown and the second allows accessing Kubernetes API on localhost bypassing authentication.

Example:

$ kubectl get pods -n kube-system --v=8

I0823 14:30:38.117371 70216 loader.go:372] Config loaded from file: C:\Users\[USER]\.kube\config

I0823 14:30:38.302372 70216 cert_rotation.go:137] Starting client certificate rotation controller

I0823 14:30:38.378981 70216 round_trippers.go:463] GET https://127.0.0.1:55790/api/v1/namespaces/kube-system/pods?limit=500

In another terminal:

$ kubectl proxy --port=8080

Starting to serve on 127.0.0.1:8080

And back on the first terminal:

$ curl -X "GET" http://localhost:8080/api/v1/namespaces/kube-system/pods?limit=500

{

"kind": "PodList",

"apiVersion": "v1",

"metadata": {

"resourceVersion": "43260"

},

"items": [...]

Not surprisingly, a Custom Resource is an API that stores a collection of API objects not provided by default but defined via Custom Resource Definition. Once the definition is submitted to Kubernetes, the API Server exposes a new HTTP API that can be used to manage the custom objects.

Of course, just the ability to handle objects that define some kind of state is pretty useless until some logic is provided. That's the job of Controllers that constantly watch resources to ensure that the current state matches the desired state.

This is the Operator Pattern. One possible use is the deployment of clusters in Kubernetes.

NOTE: For further reading about the Operator Pattern, of course, there is the Kubernetes documentation; but I found really clear the original article from CoreOS that proposed the pattern, "Introducing Operators: Putting Operational Knowledge into Software."

The Prometheus Operator

DISCLAIMER: For detailed documentation and a comprehensive list of the resource objects please refer to the Prometheus Operator project webpage.

As written on the home page of the project website:

The Prometheus Operator manages Prometheus clusters atop Kubernetes.

To do that, it defines and manages custom resources that do the following:

- Deploy pods (

Prometheus) and rules (PrometheusRule): rules that define alerts and recording rules that are precomputed expressions whose result is saved as time series - Define monitoring target for pods (

PodMonitor), static targets (Probe), or services (ServiceMonitor) - Deploy AlertManager pods (

Alertmanager) and its configuration (AlertmanagerConfig)

NOTE: Actually the Operator manages another Custom resource: ThanosRuler. Going deep into the details of Thanos is beyond my strength, but just to give an overview: combining a sidecar container in Prometheus pods and standalone components extends Prometheus for high availability.

It provides, for example, the ability to execute queries and evaluate rules across different Prometheus pods and extends the system storage to use block storage solutions instead of just the node's local storage (that is the Prometheus default). The Prometheus Operator takes care of just about the sidecar container for the Prometheus pods and the component that evaluate Prometheus rules (ThanosRuler). The choice - or the burden - of installing other components is left to the user.

To give just a high-level overview of how it works, the Prometheus resource defines, for example, the number of pod replicas, the interval between scrapes, and how much time waiting for the target to respond before erroring.

PodMonitor and ServiceMonitor work almost similarly. They select pods and services to monitor via label matching. Probe is quite different: since it is intended to monitor static targets, it actually scrapes a prober that is some kind of service that provides metrics.

So adding a target is just about defining the PodMonitor, ServiceMonitor, or Probe custom resource.

Epilogue

I asked myself a question some time ago: Can I make a system evolve if I cannot properly inspect it?

Until now, it could seem that this writing is all about monitoring but that is not entirely true: my primary goal is to inspect how a system should be designed to be monitored and observed correctly.

That's why I'm so interested in the metrics data model, metrics format, and push versus pull approach.

Implementing monitoring by design not only means providing the system topology components that retrieve metrics and can inspect other components but even implementing code that can be easily and efficiently monitored and inspected from the outside.

In a Kubernetes cluster, it is pretty common to provide every microservice of an HTTP REST API used by Kubernetes to check the health. This implies the following:

- Code must be implemented.

- Tasks must be created.

- Tests must be written and all to let Kubernetes monitor hour microservices.

Another example in a microservices architecture is the need to correlate lines in a log file with a unique ID dedicated to a request chain so that it is possible to follow what happened through the various services and instances. One way to accomplish this is to add an HTTP header after receiving the request and then propagate it through the chain until the end (the completion of the first request): this also implies that implementation must be done.

Last one: RESTful.

Even if maybe is not the main reason why people use REST - one thing that I found beautiful - is how it is naturally suitable to be monitored using params in the path and HTTP method to specify the action.

With these couple of things, it is possible to monitor an API just by identifying the method and path of the HTTP request. So, for example, thinking about a REST API that handles user login, we can answer questions like:

- How many people access my website?

- How many attempts are needed to create a new user?

But even more (and here some business comes into play):

- Since most of the time people get a Bad Request creating a user, should we improve our UI to validate the fields better?

- Since the average request per minute of the login API is higher in the evening than at lunchtime, does it still makes sense to do maintenance in the evening?

Could (or should) all this information drive business and architectural choices?

I think that a deep understanding of the mechanisms effectively in place in our systems is the basis to make the right choices.

It allows designers to maintain their knowledge about the system, even after changes are made beyond their control (hotfix). Furthermore, it allows for recursively refactoring the system design to keep it alive and efficient.

Inspection of a system makes it appear as it really is: something alive. It reveals its real nature and the real form that the initial design finally has taken.

Appendix: Monitoring and Observability Are Different Things

DORA - DevOps Research and Assessment define monitoring and observability:

Monitoring is tooling or a technical solution that allows teams to watch and understand the state of their systems. Monitoring is based on gathering predefined sets of metrics or logs.

Observability is tooling or a technical solution that allows teams to actively debug their system. Observability is based on exploring properties and patterns not defined in advance.

The difference is made by the concept of predefined and not defined in advance.

Let's try with an example. Let's say we have a log file updated in real-time.

- Check every 5 minutes for the number of errors to evaluate system health is monitoring.

- Read the logs to identify the root cause of an increase in errors is observability.

In the previous example, a file is just a tool that offers both capabilities if and only if lines report the right information so is always again designed. Does the log pattern deserve to be a design choice? Yes.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments