Java Hexadecimal Floating Point Literal

Learn more about the hexagonal floating point literal, a new functionality of Java::Geci.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeI was developing a new functionality into Java::Geci to make it less prone to code reformatting. The current release of the code will overwrite an otherwise identical code if it was reformatted. It is annoying since it is fairly easy to press the reformatting key shortcut and many projects even require that developers set their editor to automatically format the code upon save. In those cases, Java::Geci cannot be used because as soon as the code is reformatted, the generator thinks that the code it generates is not the same as the one already in the source file, updates it, and signals the change of the code failing the unit tests.

The solution I was crafting compares the Java source files — first, converting them to a list of lexical elements. That way, you can even reformat the code inserting new lines, spaces, etc., so long as long the code remains the same. To do that, I needed a simplified lexical analyzer for Java. Writing a lexical analyzer is not a big deal, I created several for different reasons since I first read the Dragon Book in 1987. The only thing I really needed is the precise definition of what are the string, character, number literals, the keywords, and so on. In short, what is the definition of the Java language on the lexical level and how is it processed. Fortunately, there is a precise definition for that, the Java Language Specification, which is not only precise but also readable and has examples. So, I started to read the corresponding chapters.

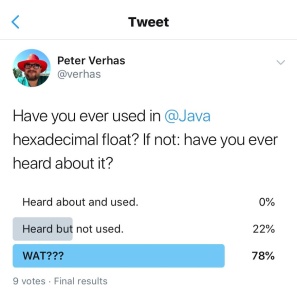

To my bewilderment, I could see there that there is a possibility in the Java language to express a floating point in hexadecimal. Strange, is it? Since I have not ever seen it, first, I thought that this was something new introduced in Java 12, but my investigation showed that it probably was introduced in Java 1.5 That was the very first Java version I really liked, but not because of hexadecimal floating points. So. this was how I met this beast in the standard face to face. I started to wonder if this beast can be found at all in the wild, or is it only something that can be seen captive in the confinements of the text of the JLS? So...

As you can see, nine decent humans answered the question, mostly saying that they have had no idea about this feature.

Probably hexadecimal floating points are the least known and used feature of the Java language right after lambdas and streams (just kidding... hexadecimal floating points are important, no?)

Even though I did some scientific study in the past, I cannot see any use of hexadecimal floating point literals.

We will get to hexadecimal floating point numbers, but to understand that, we have to know first what a floating point number generally is.

Floating point numbers have a mantissa and exponent. The mantissa has an integer and a fractional part, like iii.ffff. The exponent is an integer number. For example, 31.415926E-1 is a floating point number and an approximation for the ratio of the diameter and the circumference of a circle.

Java internally stores the float numbers on 32 bit and double number on 64 bit. The actual bits are used according to the IEEE 754 standard.

That way, the bits store a sign on a single bit, then the exponent on 8 or 11 bits, and finally the mantissa on 23 or 52 bits for 32- or 64-bit float/double respectively. The mantissa is a fractional number with a value between 1 and 2. This could be represented with a bit stream, where the first bit means 1, the second means 1/2, and so on. However, because the number is always stored normalized and, therefore, the number is always between [1 and 2), the first bit is always 1. There is no need to store it. Thus, the mantissa is stored so that the most significant bit means 1/2, the next 1/2 2, and so on, but when we need the value, we add to it 1.

The mantissa is unsigned (hence, we have a separate signum bit). The exponent is also unsigned, but the actual number of bitshifts are calculated subtracting 127 or 1023 from the value to get a signed number. It specifies how many bits the mantissa should virtually be shifted to the left or right. Thus, when we write 31.415926E-1f, then the exponent will NOT be -1. That is the decimal format of the number.

The actual value is 01000000010010010000111111011010. Breaking it down:

- 0 sign, the number is positive. So far so good.

- 10000000 128, which means we have to shift the mantissa one bit left (multiply the value by two)

- 10010010000111111011010 is:

- The hex representation of this bit stream is 0x490FDA

And here comes the...

Hexadecimal Floating Point Literal

We can write the same number in Java as 0x0.C90FDAP2f. This is the hexadecimal floating point representation of the same number.

The mantissa 0xC9aFDA should be familiar to the hexadecimal representation of the number above 0x490FDA. The difference is that the first character is C instead of 4. That is the extra one bit, which is always 1 and is not stored in the binary representation. C is 1100 while the original 4 is 0100. The exponent is the signed decimal representation of the actual bitshifts needed to push the number to the proper position.

The format of the literal is not trivial. First of all, you HAVE TO use the exponent part and the character for the exponent is p or P. This is a major difference from the decimal representation.

After a little bit of thinking it becomes obvious that the exponent cannot be denoted using the conventional e or E since that character is a legitimate hexadecimal digit and it would be ambiguous in case of numbers like 0x2e3. Would this be a hexadecimal integer or:It is an integer because we use

p and not e.

The reason why the exponent part is mandatory I can only guess. Because developers got used to decimal floating point numbers with e or E as exponent it would be very easy to misread 0xC90F.0e+3 as a single floating point number, even though in case of hexadecimal floating point p is required instead of e. If the exponent were not mandatory this example would be a legit sum of a floating point number and an integer. The same time it looks like a single number, and that would not be good.

The other interesting thing is that the exponent is decimal. This is also because some hexadecimal digits were already in use for other purposes. The float and double suffix. In case you want to denote that a literal is a float, you can append the f or F to the end. If you want to denote that this literal is double then you can append d or D to the end. This is the default, so appending D is optional. If the exponent were hexadecimal we would not know if 0x32.1P1f is a float literal or a double and having a lot of magnitudes different value. This way, that that exponent is decimal it is a float number:

Java implemented the IEEE 754 standard strictly until Java 1.2 This standard defines not only the format of the numbers when stored in memory but also defines rules how calculations should be executed. After the Java release 1.2 (including 1.2), the standard was released to make the implementations more liberal allowing to use more bits to store intermediate results. This was, and it still is, available on the Intel CPU platforms, and it is used heavily in numeric calculations in other languages like FORTRAN. This was a logical step to allow the implementations to use of this higher precision.

The same time to preserve backward compatibility the strictfp modifier was added to the language. When this modifier is used on a class, interface, or method, the floating point calculations in those codes will strictly follow the IEEE 754 standard.

- There are hexadecimal floating point literals in Java. Remember it and also what

strictfpis because somebody may ask you about it on a Java interview. No practical use in enterprise programming. - Do not use them unless it makes the code more readable. I can barely imagine any situation where this would be the case. So, simply put:

Do not use them just because you can.

Lastly, follow me on Twitter @verhas to get notification about new articles.

Oh... and yes: if you have ever used hexadecimal floating point literals in Java to make it more readable, please share the knowledge in the comments. I dare say in the name of the readers: We are interested.

Published at DZone with permission of Peter Verhas, DZone MVB. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments