How to Understand and Set Up Kubernetes Networking

Take a look at this tutorial that goes through and explains the inner workings of Kubernetes networking, including working with multiple networks.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeKubernetes networking can be a pretty complex topic. This post will give you pretty darn detailed insights on how Kubernetes actually creates networks and also how to set up a network for a Kubernetes cluster yourself.

This article doesn’t cover how to setup a Kubernetes cluster itself — for that you could use minikube to quickly spin up a test cluster. All the examples in this post will use a Rancher 2.0 cluster (but apply everywhere else as well). Even if you are planning to use any of the new public cloud-managed Kubernetes services such as EKS, AKS, GKE or IBM Cloud, you will hopefully come away with a better understanding of how Kubernetes networking works.

How to Utilize Kubernetes Networking

Many Kubernetes (K8s) deployment guides provide instructions for deploying a Kubernetes networking CNI as part of the K8s deployment. But if your K8s cluster is already running, and no network is yet deployed, deploying the network is as simple as running their provided config file against K8s (for most networks and basic use cases). For example, to deploy flannel:

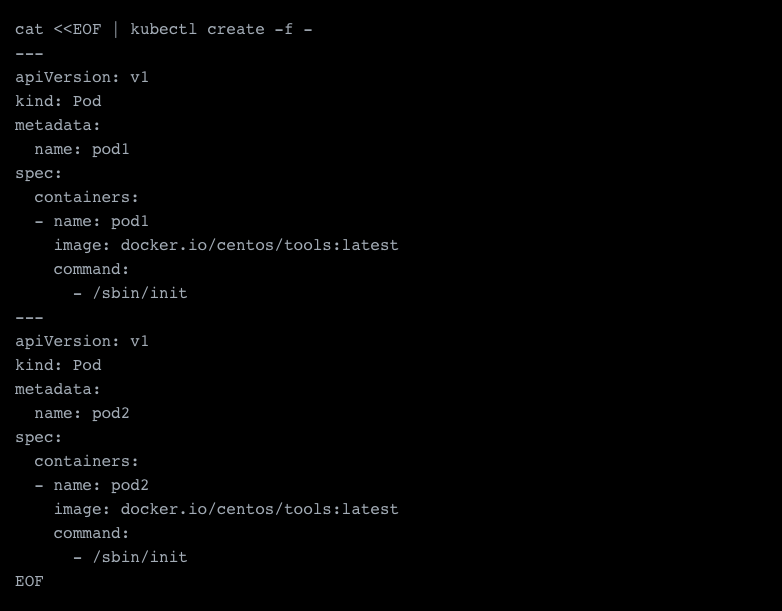

With this, K8s — from a network perspective — is ready to go. To test everything is working, we create 2 pods.

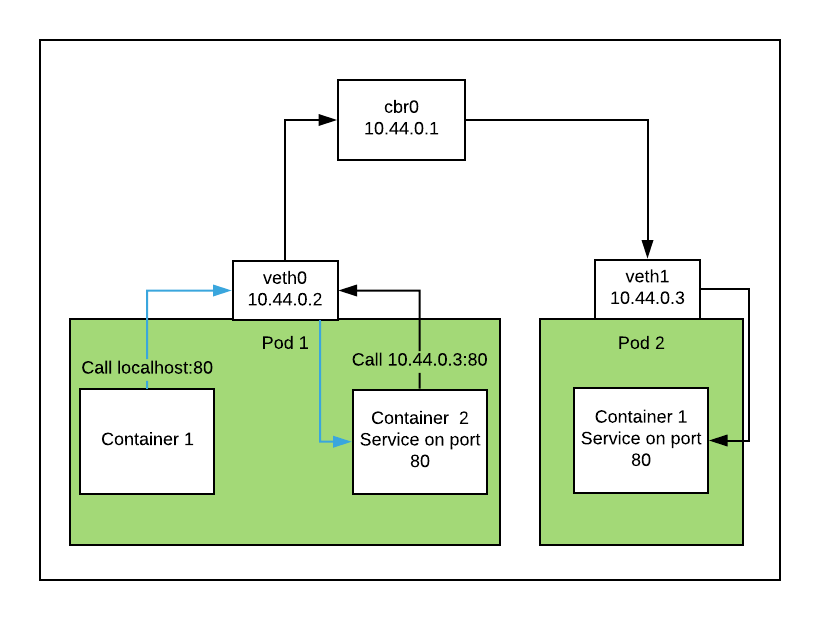

This will create two pods, which are already utilizing our driver. Looking at one of the containers, we find the network with the IP range 10.42.0.0/24 attached.

A quick ping test from the other pod shows us that the network is working properly.

How Does Kubernetes Networking Work Compared to Docker Networking?

Kubernetes manages networking through CNIs on top of Docker, and just attaches devices to Docker. While Docker with Docker Swarm also has its own networking capabilities (such as overlay, macvlan, bridging, etc), the CNIs provide similar types of functions.

It’s also important to mention that K8s does not use docker0, which is Docker’ default bridge, but rather creates its own bridge named cbr0, which was chosen to differentiate from the docker0 bridge.

Why Do We Need Overlay Networks?

Overlay networks such as vxlan or ipsec (which you might be familiar with from setting up secure VPNs) encapsulate the packet into another packet. This makes entities addressable that are outside of the scope of another machine. Alternatives to overlay networks include L3 solutions such as macvtap (lan) or even L2 solutions such as ivtap (lan), but these come with limitations or even unwanted side effects.

Any solution on L2 or L3 makes a pod addressable on the network. This means a pod is reachable not just within the Docker network, but is directly addressable from outside the Docker network. These could be public or private IP addresses.

However, communication on L2 is cumbersome and your experience will vary depending on your network equipment. Some switches need some time to register your Mac address, before it actually is reachable to the rest of the network. You could also run into trouble because the neighbor (ARP) table of the other hosts in the system still runs on an outdated cache, and you always need to run with dhcp instead of host-local to avoid conflicting ips between hosts. The mac address and neighbor table problems are the reasons solutions such as ipvlan exist. These do not register new Mac addresses but instead route traffic over the existing one (though these also have their own issues).

The conclusion — and my recommendation — is that for most users the overlay network is the default solution and should be adequate. However as soon as workloads get more advanced with more specific requirements, you will want to consider other solutions such as BGP and direct routing instead of overlay networks.

How Does Kubernetes Networking Work Under the Hood?

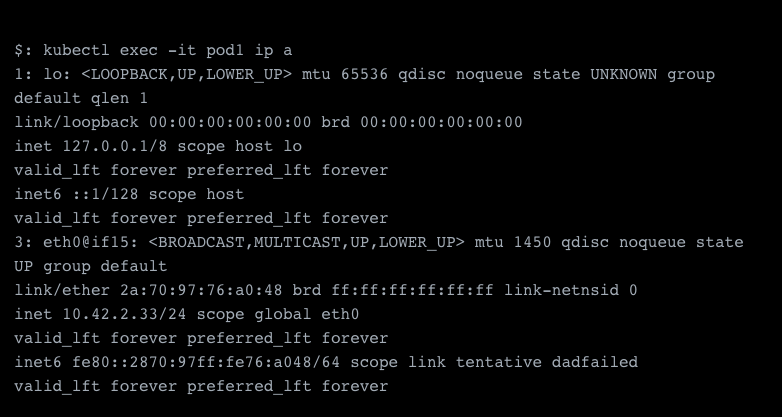

The first thing to understand in Kubernetes is that a pod is not actually the equivalent of a container, but is a collection of containers. And all these containers of the same collection share a network stack. Kubernetes manages that by setting up the network itself on the pause container, which you will find for every pod you create. All other pods attach to the network of the pause container which itself does nothing but provide the network. Therefore, it is also possible for one container to talk to a service in a different container, which is in the same definition of the same pod, via localhost.

Apart from that local communication, the communication between pods looks pretty much the same as container-to-container communication in Docker networks.

Kubernetes Traffic Routing

There are two scenarios that I’ll go into more detail in explaining how traffic gets routed between pods.

1. Routing Traffic on The Same Host:

There are two situations where the traffic does not leave the host. This is either when the service called is running on the same node, or it is the same container collection within a single pod.

In the case of calling localhost:80 from container 1 in our first pod and having the service running in the container 2, the traffic will pass the network device and forward the packet to its destination. In this case, the route the traffic travels is quite short.

It gets a bit longer when we communicate to a different pod. The traffic will pass over to cbr0, which next will notice that we communicate on the same subnet and therefore directly forwards the traffic to its destination pod, as shown below.

2. Routing Traffic Across Hosts:

This gets a bit more complicated when we leave the node. cbr0 will now pass the traffic to the next node, whose configuration is managed by the CNI. These are basically just routes of the subnets with the destination host as a gateway. The destination host can then just proceed on its own cbr0 and forward the traffic to the destination pod, as shown below.

What Exactly is a CNI?

A CNI, which is short for Container Networking Interface, is basically an external module with a well-defined interface that can be called by Kubernetes to execute actions to provide networking functionality.

You can find the maintained reference plugins, which include most of the important ones in the official repo of container networking here.

CNI version 3.1 is not very complicated. It consists of three required functions, ADD, DEL and VERSION, which should do what they sound like they should as far as managing the network. For a more detailed description of what each function is expected to return and gets passed, you can read the spec here.

The Different CNIs

To give you a bit of orientation, we will look at some of the most popular CNIs.

Flannel

Flannel is a simple network and is the easiest setup option for an overlay network. Its capabilities include native networking but has limitations when using it across multiple networks. Flannel is for most users, beneath Canal, the default network to choose, a simple option to deploy, and even provides some native networking capabilities such as host gateways. Flannel has some limitations, though, including lack of support for network security policies and the capability to have multiple networks.

Calico

Calico takes a different approach than flannel. It is technically not an overlay network, but rather a system to configure routing between all systems involved. To accomplish this, Calico leverages the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) which is used for the Internet in a process named peering, where every peering party exchanges traffic and participates in the BGP network. The BGP protocol itself propagates routes under its ASN, with the difference that these are private and there isn’t a need to register them with RIPE.

However, for some scenarios, Calico works with an overlay network — in this case IPINIP, which is always used when a node is sitting on a different network in order to enable the exchange of traffic between those two hosts.

Canal

Canal is based on Flannel but with some Calico components such as felix (the host agent), which allows you to utilize network security policies. These are normally missing in Flannel. So it basically extends Flannel with the addition of security policies.

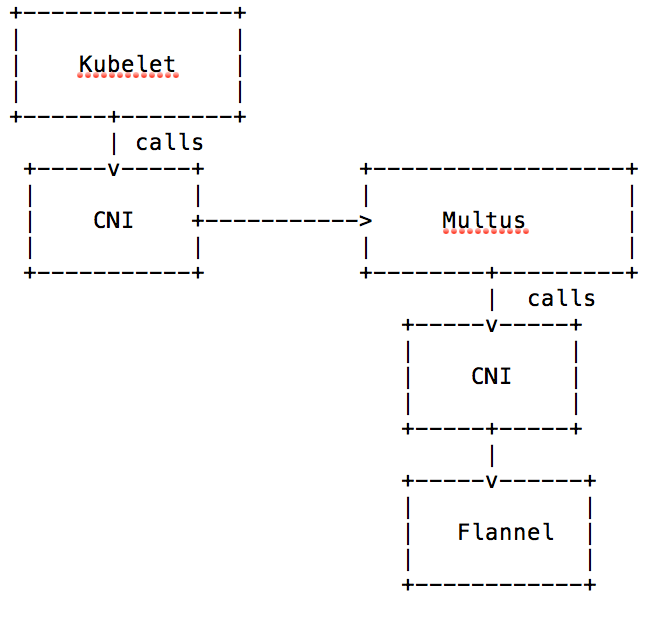

Multus

Multus is a CNI that actually is not a network interface itself. It orchestrates multiple interfaces and without an actual network configured, pods couldn’t communicate with Multus alone. So Multus is an enabler for multi-device and multi-subnet networks. The graphic below shows how this works, Multus itself basically calls the real CNI instead of the kubelet and communicates back to the kubelet the results.

Kube-Router

Also worth mentioning is kube-router, which — like Calico — works with BGP and routing instead of an overlay network. Also like Calico, it utilizes IPINIP where needed. It also leverages ipvs for load-balancing.

Setting up a Multi-Network K8s Cluster

In the cases when you need to utilize multiple networks, you’ll likely be required to use Multus. While Multus is quite mature and works without too many issues, you should know that there are currently some limitations.

One of that limitations is that port mapping does not work, which is documented and tracked on the following issue on Github. This is going to be fixed in the future. But if you currently need mapping ports (either nodePort configs or hostPort configs), you won’t be able to do that due to the bug referenced.

Setting Up Multus

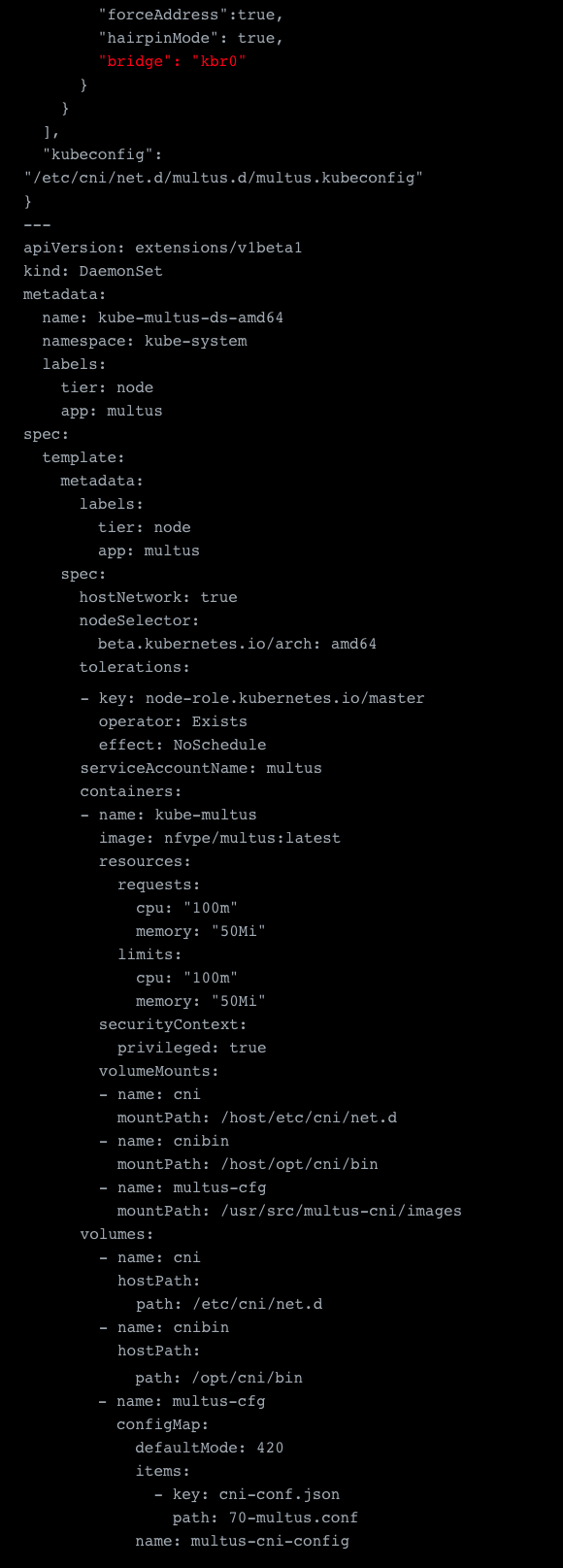

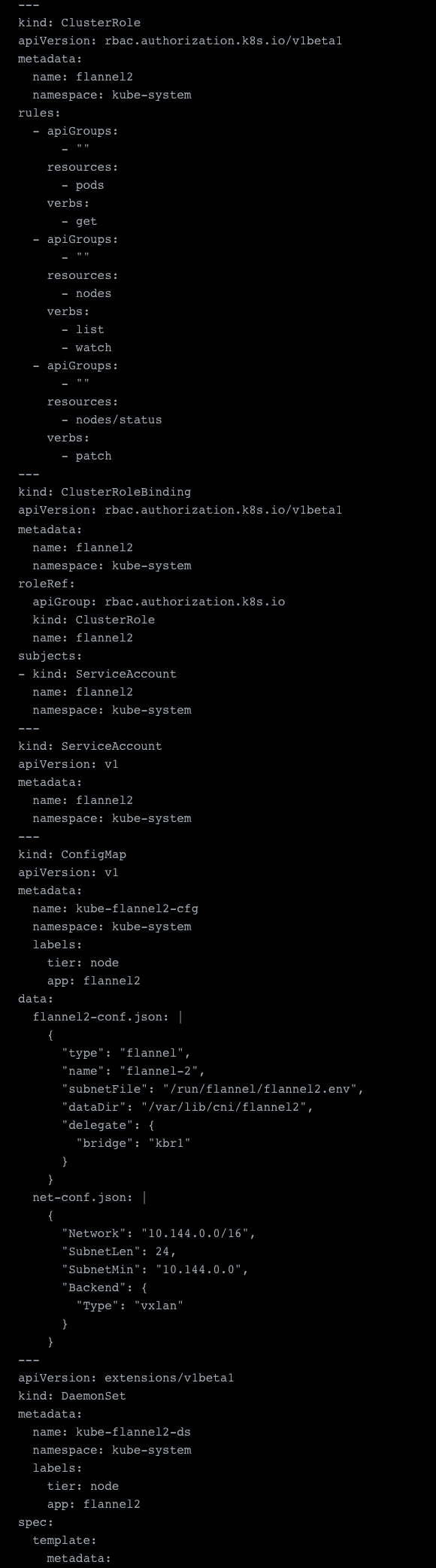

The first thing we need to do is to setup Multus itself. This is pretty much the config from the Multus repositories examples, but with some important adjustments. See the link below to the sample.

The first thing was to adjust the config map. Because we plan to have a default network with Flannel, we define the configuration in the delegates array of the Multus config. Some important settings here marked in red are “masterplugin”: true and to define the bridge for the flannel network itself. You’ll see why we need this in the next steps. Other than that there isn’t much else to adjust except adding the mounting definition of the config map, because for some reason this was not done in their example.

Another important thing about this config map is that everything defined in this config map is the default networks that are automatically mounted to the containers without further specification. Also, should you want to edit this file, please note you either need to kill and rerun the containers of the daemonset, or reboot your node to have the changes take effect.

The sample yaml file:

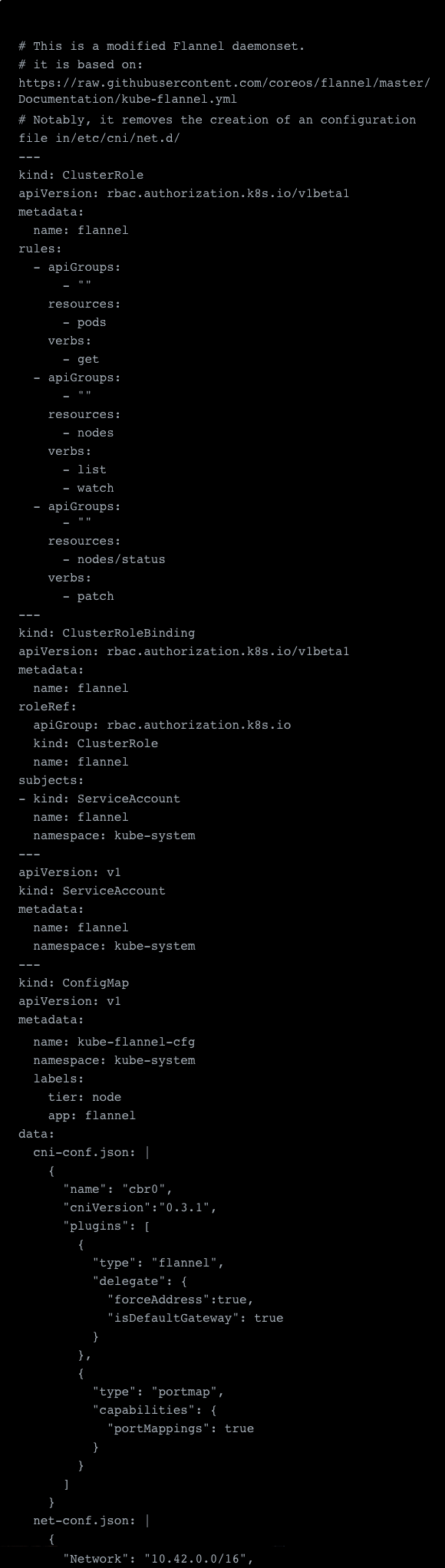

Setting Up the Primary Flannel Overlay Network

For the primary Flannel network, things are pretty much very easy. We can take the example from the Multus repository for this and just deploy it. The only adjustments that have been made here are the CNI mount, adjustment of tolerations and some adjustments made for the CNI settings of Flannel. For example, adding “forceAddress”:true and removing “hairpinMode”: true .

This was tested on a cluster that was set up with RKE, but should work on other clusters as well as long as you mount the CNIs from your host correctly, in our case /opt/cni/bin.

The Multus team themselves did not really change much; they only commented out the initcontainer config, which you could just safely delete. This is made since Multus will set up its delegates and will act as the primary “CNI.”

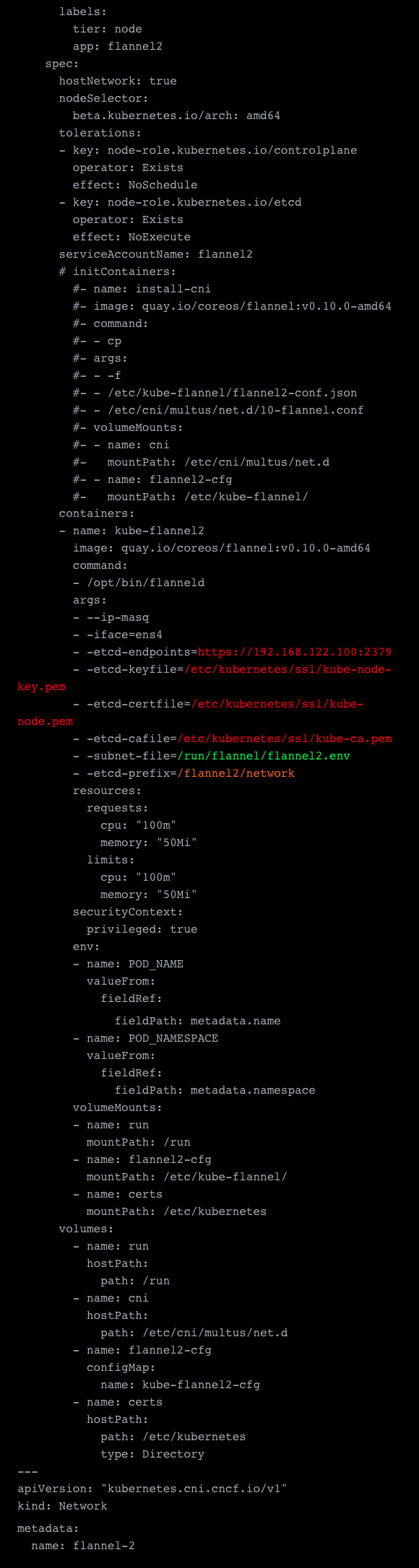

Here's the modified Flannel daemonset:

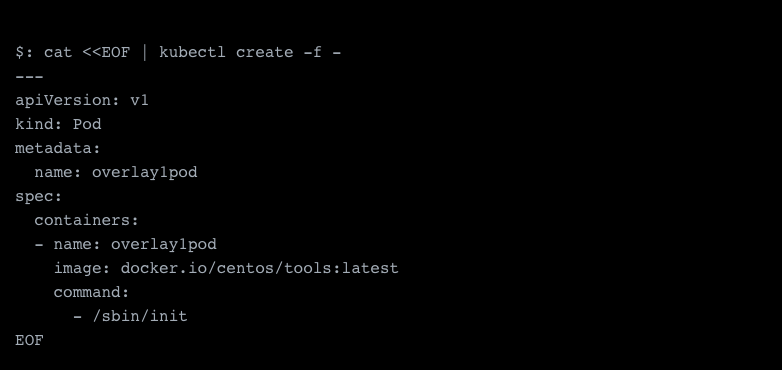

With these samples deployed, we are pretty much done and our pods should now be assigned an IP address. Let’s test it:

As you can see, we have successfully deployed a pod and were assigned the IP 10.42.2.43 on the eth0 interface, which is the default interface. All extra interfaces will appear as netX, i.e. net1.

Setting Up the Secondary Network

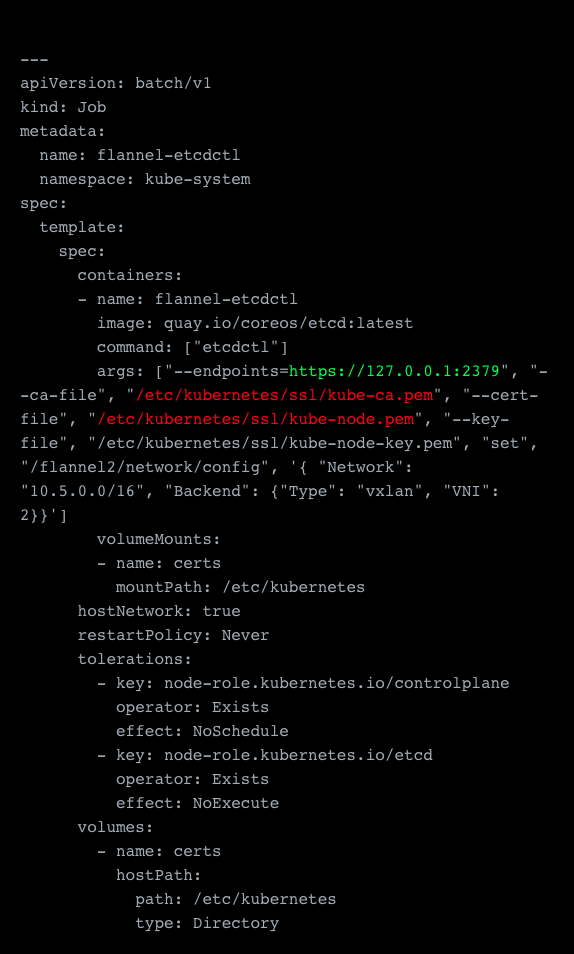

The secondary network needs a few more adjustments and these are all made on the assumption that you want to deploy vxlan. To actually serve a secondary overlay we need to change the VXLAN Identifier “VIN,” which by default is set to 1, and which is now already taken by our first overlay network. So we can change this by configuring the network on our etcd server. We use the clusters own etcd, here marked in green (and we assume that the job runs on the host running the etcd client) and mount in our keys, here marked in red, from the local host which in our case are stored in the /etc/kubernetes/ssl folder.

The entire sample YAML file:

Next, we can actually deploy the secondary network. The setup of this pretty much looks the same as the primary one, but with some key differences. The most obvious is that we changed the subnet, but we also need to change a few other things.

First of all we need to set a different dataDir, i.e. /var/lib/cni/flannel2, and a different subnetFile, i.e. /run/flannel/flannel2.env. This is needed because they are otherwise occupied and already used by our primary network. Next we need to adjust the bridge because kbr0 is already used by the primary Flannel overlay network.

The remaining configuration required includes changing it to actually target our etcd server which we configured before. In the primary network, this was done by connecting to the K8s API directly, which is done via the –kube-subnet-mgr flag. But we can’t do that because we also need to modify the prefix from which we want to read. You can see this below marked in orange and settings for our cluster etcd connection in red. The last setting is to specify the subnet file again, marked in green in the sample. Last but not least, we add a network definition. The rest of the sample is identical to our main networks config.

See the sample config file for the above steps:

Once this is done we have our secondary network ready.

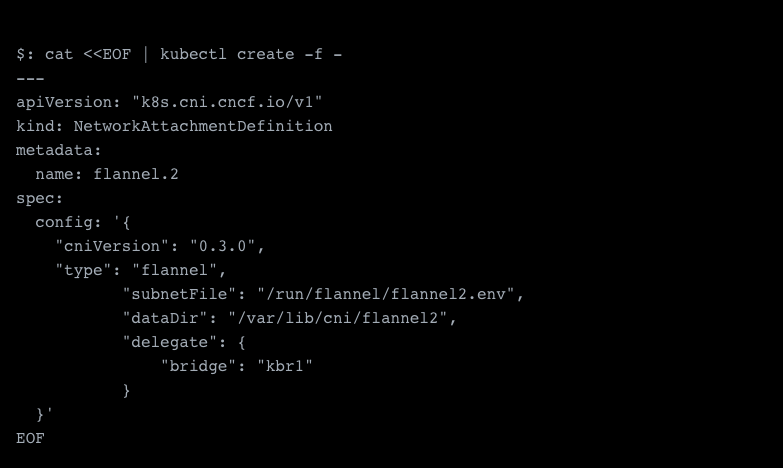

Assigning Extra Networks

Now that we have a secondary network ready we also need to assign this. To do this we also need to first define a NetworkAttachmentDefinition, which we can use afterward to assign this network to the container. This is basically the dynamic alternative to the configmap we set up before when initializing Multus. This way we can mount the networks we need on demand. In this definition, we need to specify the network type, in our case flannel and also necessary configurations. This includes the before mentioned subnetFile, dataDir and bridge name.

The last thing we need to decide is the name for the network, so we name ours flannel.2.

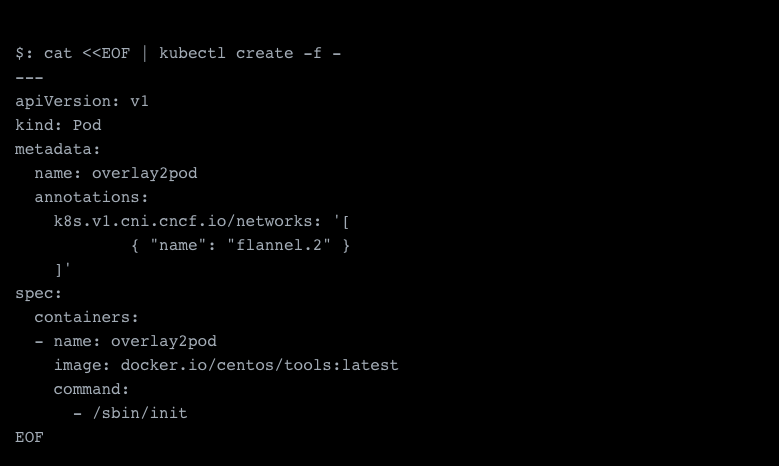

Now we're finally ready to spawn our first pod with our secondary network.

This should create your new pod with your secondary network, and we should see those attached as additional network interfaces now.

Success, we see the secondary network which was assigned 10.5.22.4 as its ip address.

Troubleshooting

Should this example not work for you, you will need to look at the logs of your kubelet.

One common issue is missing CNIs. In my first tests, I was missing the bridge CNI since this was not deployed by RKE. But fixing this is as easy as downloading them from the container networking repo.

External Connectivity and Load Balancing

Now that we have a network up and running, the next thing we want is to make our app reachable and configure them to be highly available and scalable. While HA and scalability are not solely achieved by load balancing it is the key component we need to have in place.

Kubernetes basically has four concepts to make an app externally available.

Using Load Balancers

Ingress

An Ingress is basically a load balancer with Layer 7 capabilities, specifically HTTP(s). The most commonly used implementation of an ingress controller is the NGINX ingress. But this highly depends on your needs and your use case and when in doubt you can default to whichever solution you want to use. For example, traefik or HA Proxy for which ingress controllers already exists. See the traefik guide for an example on how to set up a different ingress controller.

Configuring an ingress is quite easy. In the following example, you see an example of a linked service. In blue, you will find the basic configuration which in this example points to a service. In green, you find the configuration needed to link your SSL certificate unless you do not employ SSL (you will need this certificate installed before though). And last but not least, in brown, you will find an example to adjust some of the detailed settings of the NGINX ingress. The latter ones you can look up over here.

Layer 4 Load Balancer

The Layer 4 load balancer, which is defined in Kubernetes with type: LoadBalancer , is a service provider dependent load balancing solution. For an on premise machine this will be most probably HA Proxy or a routing solution. Cloud providers may use either their own solution, have special hardware in place or resort to an HA Proxy or a routing solution as well. Should you manage a bare metal installation of a K8s cluster, you might want to give this a look.

The big difference is that the layer 4 load balancer does not understand high-level application protocols (layer 7) and is only capable of forwarding traffic. Most of the load balancers on this level also support SSL termination. This typically needs to be configured through annotations and is not standardized. So look this up in the docs of your cloud provider accordingly.

Using {host,node} Ports

A {host,node}Port is basically the equivalent to docker -p port:port , especially the hostPort. The nodePort, unlike the hostPort, is available on all nodes instead of only on the nodes running the pod. For nodePort kubernetes creates a clusterIP first and then load balances traffic over this port. The nodePort itself is just an iptable rule to forward traffic on the port to the clusterIP.

A nodePort is rarely used except in quick testing and only really needed in production if you want every node to expose the port, i.e. for monitoring. Most of the time you will want to use a Layer 4 load balancer instead. And hostPort is only really used for testing purposes or very rarely to stick a pod to a specific node and publish under a specific ip address pointing to this node.

To give you an example, a hostPort is defined in the container spec, like the following:

What is a ClusterIp?

A clusterIP is an internally reachable IP for the kubernetes cluster and all services within it. This IP itself load balances traffic to all pods that matches its selector rules. A clusterIP also automatically gets generated in a lot of cases, for example when specifying a type: LoadBalancer service or setting up nodePort. The reason behind this is that all the load balancing happens through the clusterIP.

The clusterIP itself as a concept was created to solve the problem of multiple addressable hosts and the effective renewal of those. It is much easier to have single IP that does not change than to refetch data all the time via service discoveries all the time for all natures of services. Although there are times when it is appropriate to use service discovery instead if you want explicit control, for example in some microservice environments.

Common Troubleshooting

If you use a public cloud environment and set up the hosts manually, your cluster might be missing firewall rules. For example, in AWS you will want to adjust your security groups to allow inter-cluster communication as well as ingress and egress. If you don't, this will lead to an inoperable cluster. Make sure you always open the required ports between master and worker nodes. The same goes for ports that you open on the hosts directly, i.e. hostPort or nodePort.

Network Security

Now that we have set up all of our Kubernetes networking, we also need to make sure that we have some security in place. A simple rule in security is to give applications the least amount of access they need to function. This ensures, to a certain degree, that even in the case of a security breach attackers will have a hard time digging deeper into your network. While it does not completely secure you, it certainly makes it a heck of a lot harder and more time-consuming. This is important because it gives you more time to react and prevent further damage, and can often prevent the damage itself. A prominent example is the combination of different exploits/vulnerabilities of different applications, which the attacker is only able to pursue if there is actually any attack surface reachable from multiple vectors (e.g. network, container, host).

The options here are either to utilize network policies, or to look toward 3rd party security solutions for container network security. With network policy, we have a solid base to ensure that traffic only flows where it should flow, but this only works for a few CNIs. They work, for example, with Calico and Kube-router. Flannel does not support it but luckily as of recently, you can move to Canal, which makes the network policy feature from Calico usable by Flannel. For most other CNIs there is no support and also no support planned.

But this is not the only issue. The problem is that a network policy rule is only a very simple firewall rule targeting a certain port. This means you can’t apply any advanced settings. For example, you can’t block just a single container on demand should you detect something is suspicious with this container. Further network rules do not understand the traffic, so you don’t have any visibility of the traffic flowing, and you’re purely limited to creating rules on the Layer 3 and 4 levels. And, lastly, there is no detection of network-based threats or attacks such as DDoS, DNS, SQL injection and other damaging network attacks that can occur even over trusted ip addresses and ports.

This is where specialized container network security solutions provide the security needed for critical applications such as financial or compliance driven ones. I personally like NeuVector for this; it has a container firewall solution that I had experience with deploying at Arvato/Bertelsmann, and it provided the Layer 7 visibility and protection we needed.

It should be noted that any network security solution must be cloud-native and auto-scaling and adapting. You can’t be checking on iptable rules or having to update anything when you deploy new applications or scale your pods. Perhaps for a simple application stack on a couple nodes you could manage this all manually, but for any enterprise, deployment security can’t be slowing down the CI/CD pipeline.

In addition to the security and visibility, I also found that having connection and packet-level container network tools helped debug applications during test and staging. With a Kubernetes network you’re never really certain where all the packets are going and which pods are being routed to unless you can see the traffic.

Some Advice on Choosing the Network CNI

Now that Kubernetes networking and CNIs have been covered, one big question always comes up. Which CNI solution should choose? I will try to provide some advice about how to go about making this decision.

First, Define the Problem

The first thing for every project is to define the problem you want to solve first in as much detail as possible. You will want to know what kind of applications you want to deploy and what kind of load they generate. Some of the questions you could ask yourself are:

Is my application:

Heavy on the network?

Sensitive to latency?

A monolith?

A microservice architected service?

On multiple networks?

Can I Withstand Major Downtime? Or Even Minor?

This is an important question because that you should decide up front — because if you choose one solution now and later on you want to switch, you will need to re-setup the network and redeploy all your containers. Unless you already have something in place like Multus and work with multiple networks, this will mean a downtime for your service. Most of the time it will be fine if you have a planned maintenance window, but as you grow, zero downtime becomes more important!

My Application Is on Multiple Networks

This scenario is quite common in on-premise installations. In fact, if you only want to separate the traffic going over the private network and the public network, this will require you to either set up multiple networks or have clever routing.

Is There a Certain Feature I Need from The CNIs?

Another thing influencing your decision can be that you want some features of the CNIs not available to other CNIs. For example, you want to utilize Weave or you want more mature load balancing through ipvs.

What Network Performance Is Required?

If you answered that your application is sensitive to latency or heavy on the network, you might want to avoid any overlay network. Overlays can be expensive on performance and even more so at scale. If this is the case the only way to improve performance on the network is to avoid overlays and utilize networking utilities like routing instead. When you look for network performance you have a few choices, for example:

Ipvlan: Ipvlan could be an option for you, it has a good performance. But it also caveats, i.e. you can’t use macv{tap,lan} at the same time on the same host.

Calico: Calico is not the most user-friendly CNI, but it provides you with much better performance compared to vxlan and can be scaled without issues.

Kube-Router: Kube-router will give you better performance (like Calico), since they both use BGP and routing, plus support for LVS/IPVS. But it might not be as battle-tested as Calico.

Cloud Provider Solutions: Last but not least, some of the cloud providers do provide their own Kubernetes networking solutions that may or may not perform better. Amazon, for example, has their aws-vpc which is supported on flannel. Aws-vpc performs in most scenarios about as good as ipvlan.

But I Just Want Something That Works!

Yes, that is understandable, and this is the case for most users. In this case probably canal or Flannel with vxlan will be the way to go because it is a no-brainer and just works. However, as I said before, vxlan is slow and it will cost you significantly more resources as you grow. But this is definitely the easiest way to start.

Just Make a Decision

It really is a matter of making a decision rather than making none at all. If you don’t have specific features requirements it is fine to start with Flannel and vxlan. It will involve some work to migrate later if you’ve deployed to production but it is better to make decision that is wrong in the long term than making no decision at all.

With all this information, I hope that you will have some relevant background and a better understanding of how Kubernetes networking works.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments