Two Ways to Dockerize Spring Boot Applications

This article looks at two common options for Dockerizing Spring Boot applications. We will use a simple REST application as a running example.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeMicroservices are often built with the Spring Boot framework and deployed with Docker. This paper looks at two common options for Dockerizing Spring Boot applications. Throughout we will use a simple REST application as a running example.

We will use Spring Tool Suite to build the application, though neither the IDE nor the application matter all that much, as long as we have the pom file. We will assume that the reader has minimal knowledge of Docker, though as we shall see one of the options we will discuss, requires no knowledge of Docker. Here then is the REST controller:

package hello;

import org.springframework.boot.SpringApplication;

import org.springframework.boot.autoconfigure.SpringBootApplication;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.RequestMapping;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.RestController;

public class Application {

("/")

public String home() {

return "Hello from Spring Boot in Docker";

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

SpringApplication.run(Application.class, args);

}

}

We build this into a fat jar in the target directory. The simplest way to Dockerize it is to stuff the fat jar into a container:

Dockerfile

xxxxxxxxxx

FROM adoptopenjdk:11-jre-hotspot

ARG JAR_FILE=target/*.jar

COPY ${JAR_FILE} app.jar

ENTRYPOINT ["java","-jar","/app.jar"

This turns out to be a very bad idea. To see why recall that every instruction of the Docker file creates a layer in the image. In this case, our application and all its dependencies are put in one layer. If we keep changing the application then the image is rebuilt from scratch every time even though the dependency jars rarely change. This leads to slow builds.

A better option is to observe the old software design principle and separate what changes from what stays the same. We can do this by putting the dependencies in the bottom layer and the application layer on top. Docker will then cache the dependency layer and every time we change the application and rebuild the image, the dependency layer will be retrieved from cache leading to faster builds.

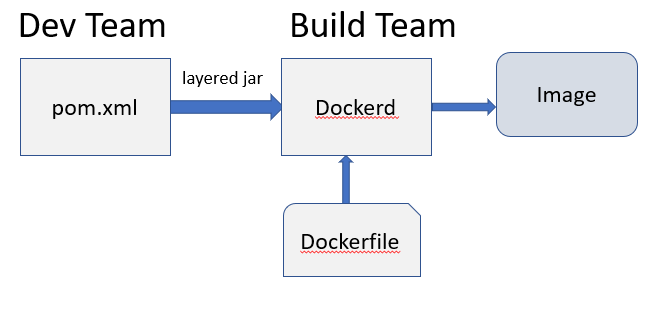

So much for the throat clearing. For our first option, we consider a very traditional organization where the development team and the build team are separate; the developers don’t know anything about Docker and don’t want to know. The development team builds applications and give it to the build team to manage the builds and deployment.

The fat jar is organized into three parts:

- Classes used to bootstrap jar loading

- Your application classes in BOOT-INF/classes

- Dependencies in BOOT-INF/lib

You can see this by inspecting the jar file (jar tvf app.jar). We can take advantage of this to separate the layers. We can of course extract the jar file and then, in a Dockerfile move and copy the layers. But Spring makes it even easier with layered jars. So, the developers tweak the pom file to enable layers

xxxxxxxxxx

<plugins>

<plugin>….

<configuration>

<layers>

<enabled>true</enabled>

</layers>

</configuration>

</plugin>

</plugins>

The dev team hands over the fat jar they have built to the build team.

We can list the layers

xxxxxxxxxx

java -Djarmode=layertools -jar app.jar list

dependencies

spring-boot-loader

snapshot-dependencies

application

Now the build team can extract and copy the layers of the jar file to layers of the image in a multi-stage docker file (a multi-stage docker file is one with many named build stages)

Dockerfile

xxxxxxxxxx

FROM adoptopenjdk:11-jre-hotspot as builder

WORKDIR application

ARG JAR_FILE=target/*.jar

COPY ${JAR_FILE} application.jar

RUN java -Djarmode=layertools -jar application.jar extract

FROM adoptopenjdk:11-jre-hotspot

WORKDIR application

COPY application/dependencies/ ./

COPY application/spring-boot-loader/ ./

COPY application/snapshot-dependencies/ ./

#COPY application/resources/ ./

COPY application/application/ ./

ENTRYPOINT ["java", "org.springframework.boot.loader.JarLauncher"]

Note that there is nothing in the Dockerfile that is specific to the application, which is why we used the jarlauncher. It will start the image a little slower but no big deal. Also, we assume that there is a local instance of Docker

We can build the image as usual (calling the image “example”)

docker build. -tag example

xxxxxxxxxx

docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

example latest de7a3bb4889e 7 days ago 243MB

Now run it:

docker run -it -p80:8080 example:latest

And go to localhost in a browser and see that you get “Hello from Spring Boot in Docker”.

The second option is for a more modern organization and organized per the microservices principles. Here the development team itself is responsible for building and deploying the docker image. But the dev team still knows nothing about Docker. We use jib. From the Google team’s description:

“Jib is a fast and simple container image builder that handles all the steps of packaging your application into a container image. It does not require you to write a Dockerfile or have Docker installed, and it is directly integrated into Maven and Gradle—just add the plugin to your build and you'll have your Java application containerized in no time”

To use jib we modify the pom to insert:

xxxxxxxxxx

<plugin>

<groupId>com.google.cloud.tools</groupId>

<artifactId>jib-maven-plugin</artifactId>

<version>2.4.0</version>

<configuration>

<to>

<image>jibexample2</image>

</to>

</configuration>

</plugin>

Now we assume, for this example that the team has a local instance of Docker running although that is not necessary

We have named the image as jibexample2. Now build the project

mvn compile jib:dockerBuild

If you list the docker images (docker images), you will see:

"REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE"

jibexample2 latest 7b84d5781eca 50 years ago 142MB

That’s it! No Docker file and no knowledge of Docker. Note the size. You can inspect the image via docker inspect and see that the entry point is hello. Application and you can see the layers listed. The layers are a bit different:

- Classes

- Resources

- Project dependencies

- Snapshot dependencies

- All other dependencies

The base image is distroless java. Distroless images contain only runtime dependencies. They do not contain package managers, shells, or any other programs you would expect to find in a standard Linux distribution. You can change the base image. Jib figures out the ENTRYPOINT. For comparison here is the Dockerfile implicitly used by Jib.

xxxxxxxxxx

# Jib uses distroless java as the default base image

FROM gcr.io/distroless/java:latest

COPY dependencyJars /app/libs

COPY snapshotDependencyJars /app/libs

COPY projectDependencyJars /app/libs

COPY resources /app/resources

COPY classFiles /app/classes

# Jib's default entrypoint when container.entrypoint is not set

ENTRYPOINT ["java", jib.container.jvmFlags, "-cp", "/app/resources:/app/classes:/app/libs/*", jib.container.mainClass]

CMD [jib.container.args]

Also instead of jib:dockerBuild we can use jib:build which will push the image to a remote registry if you provide the credentials. With jib:buildTar you can save the image as a tarball to target/jib-image.tar which you can inspect and import into Docker. There are tons of other configurations for Jib.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments