Custom Code Inspections in IntelliJ

Learn more about custom code inspections with IntelliJ.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeThere are many code analyzer tools on the market for Java, some of them are even used as de-facto standards like Checkstyle, PMD, and SpotBugs, and they have immense value in preventing developers, making many common mistakes and coding errors, thus speeding up development process, lessening bug fixing efforts, and many many more.

Context and Motivation

A few years ago, I was on a huge project that, of course, used these libraries to improve software quality and help developers' lives.

I was part of a small team that was developing a Java-based test automation framework for internal usage, but it was used widely and extensively in our teams — not just by test automation engineers but also by back-end and front-end developers, so it was almost unavoidable and evident that we would run into some common mistakes and misusage.

For a while, it worked fine and we identified them during the code review process, but after some time, I wanted to make sure that those coding mistakes don't even reach pull requests, thus lowering the code review efforts and they would even be displayed during the coding process in the IDE.

Then, I bumped into IntelliJ's inspections.

It was obvious that IntelliJ has built-in inspections (even for specific Java libraries and frameworks), but you can also make custom ones via its tool called Structural Search and Replace Templates. That was the feature that came in handy because I had the ability to create custom code checks specifically for our framework. Now, I could have used PMD, for instance, to create them, but I'm not sure if such checks would need to be reimplemented to work with an IntelliJ inspection plugin (but they definitely need a plugin as an adapter between PMD and IntelliJ), and since this Structural Search and Replace tool is not a well-documented feature, I felt the challenge and I had a calling to experiment with it.

This tool has a GUI-based editor that produces XML configs. That is what I'm going to go into the details of in this article.

Let's use an example from the Mockito library.

Mockito Example

Until a certain version of Mockito, it was not possible to mock/spy final classes, and even after that version, the inline mocking feature is disabled by default for now. So, I guess there are still many projects that use a Mockito version or use Mockito in a way that they are unable to mock final classes.

Now, when I was writing unit tests where there were occasions when I wrote a whole unit test, it took let's say 10-15 minutes to figure out how to mock the dependencies of the class under test. Then, when I ran the test, it turned out that one of the classes could not be mocked because it is final, and maybe even was meant to be final, so I basically based my test on a false assumption.

Having an inspection for that, highlighting the problematic code snippet even before running the test, and showing me a message saying something like "Final classes cannot be mocked, you idiot!," would have been pretty useful, and I could have saved that time and spent it on other tasks. Multiply this wasted time by the number times you have made this mistake or similar ones, and you can calculate how much time would have been saved with a simple check like this.

I did some investigating and found that there are many libraries that don't have their own inspections either in the XML form and especially not in the form of an IntelliJ plugin.

A great exception to this is Lombok's IntelliJ plugin (if we are talking only about specific libraries) but I could mention some Checkstyle and PMD plugins as well. But I couldn't find one for Mockito.

Assemble a Custom Inspection

Let's create an inspection for @Mock and @Spyannotated fields marking them as problematic if the field type (and not the field itself) is final.

You can find custom inspections under Settings > Editor > Inspections > General > Structural Search Inspection. First, you need to enable it; after that, at the right side, you can add either a Search Template or a Replace Template. The difference between them is that while the former one only highlights code snippets; the latter one also provides a quick fix for that particular code part.

I'm not going to provide a step-by-step tutorial for assembling a template, but I'm going to give a brief explanation on how it works.

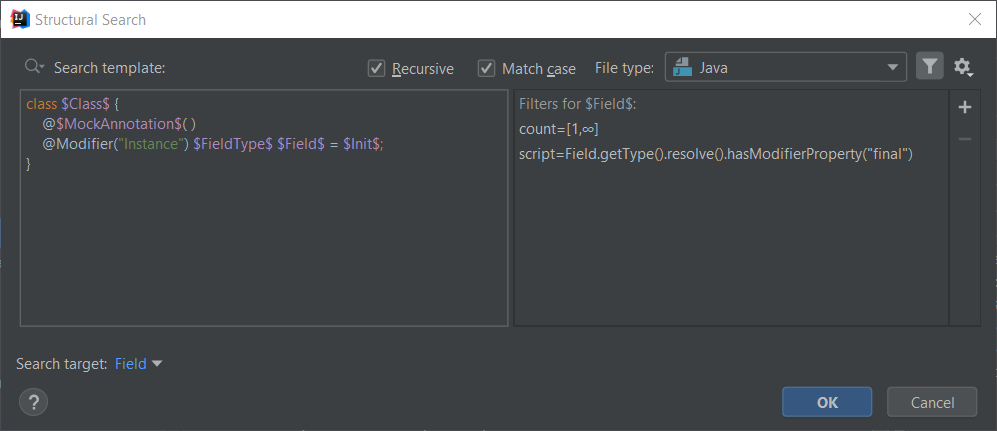

The following is the template text of the whole inspection (with customizable template variables enclosed by the $character):

class $Class$ {

@$MockAnnotation$( )

@Modifier("Instance") $FieldType$ $Field$ = $Init$;

}

I think its quite understandable and has a nice visual representation of what is going on here, at least partially: The inspection should search for instance fields of classes that are annotated as at least @Mock. The only missing part is that the field type should be final.

Let's take a look at the configuration of the template variables.

One can define different filters on them with which the search can be restricted to certain values and data or enriched with custom validation logic.

The $MockAnnotation$variable has a Text Filter defined in which the annotation is referenced as a regexp: org\.mockito\.(Mock|Spy)to search for these two annotations.

The $Field$variable has two filters:

- A Count Filter defined as a [1,Infinite] range telling the tool that there may be at least one, or an infinite number of occurrences of such fields so that you make sure that all are found and highlighted.

- A Script Filter in which you can write any kind of Groovy script you want, having the ability to write any custom validation logic with the extra ability to access IntelliJ's internal API:

Field.getType().resolve().hasModifierProperty("final")In the Script Filter, what happens is that you can reference the template variables (in this case, Field), which is handled as an AST node (actually as IntelliJ's own AST implementation); the field's type is converted to a class AST node type on which the modifiers can be queried. The returned value from a Script Filter should be a boolean; in this case, whether the field type is final or not.

The $Init$variable has a Count filter defined as the [0,1] range, making the initialization part optional in the search.

Here, you can see the inspection in action:

Pros and Cons

Of course, this tool and solution has its own limitations and pros and cons as well, so I would like to mention some of them from both sides.

Pros

Whether in this form or as an IntelliJ plugin, library-specific inspections, signaling misused or bad constructs, or even providing replacements/quick fixes for them, this tool:

- Can help to find coding issues even before a test or an application would be built or even started,

- Can help to reduce development and code review efforts

This makes the whole development process and code quality faster and better.

Cons

While I find these inspections generally useful, in this form, they may not be the best fit for projects that develop and maintain a high number of applications because the maintenance of these inspections may increase significantly with that. An IntelliJ plugin would be a better fit; the project would just need to make sure that everyone installs and uses it.

Final Thoughts

Though on the project we didn't measure how much value those inspections (for our internal automation framework) gave, I personally find them very useful, and after creating more and more of them, they make my coding life easier and easier.

If you are interested in using such inspections, you can head over to this IntelliJ-inspections GitHub project where you can find a collection of inspections for different Java libraries.

If you are also interested in learning how to create such inspections and learn how they work, you can find more details in the official documentation and on the website called IJnspector that is dedicated to providing detailed tutorials about specific inspections and how certain aspects/parts of the tool work.

The tutorial for the inspection mentioned in this article can be found at Mockito cannot mock/spy final classes.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments