10 Misconceptions About Passkey Implementation: It’s Harder Than You Think!

Read about the challenges, pitfalls, and misconceptions you will face while implementing passkey-first authentication on your own.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For Free“Ah yes passkeys, pretty cool technology, and great that there’s already wide support, plus an open standard that they are built on. I’ll just grab one of the libraries for my framework and that should do the job. I don’t think I need any help or service. I’m a decent coder and have added auth packages dozens of times in the past.”

This is a typical conversation I have with many developers. And I have to admit, that this was also my initial thought when I encountered passkeys for the first time in May 2022: It shouldn’t be too hard. It shouldn’t be too complicated. Hey, in the end, it’s just another way of doing (passwordless) authentication. And here I am in mid-2024, still discovering new cases you need to take care of in real-life applications. That’s the reality — which fascinates me.

With this blog post, I want to share with you the learnings on my way when working on a passkey-first auth solutions. All the pitfalls, hard truths, unknown unknowns, and misconceptions should be uncovered, so that you know what to consider when implementing your own passkey-based authentication.

Whether you're at the initial stages of adoption, considering enhancing your existing systems with a passkey, or starting a passkey-first authentication project, this guide will help you avoid the 10 most common pitfalls.

1. Creating Passkeys Is Just Triggering navigator.credentials.create()

I’ve seen this WebAuthn JavaScript API where I can simply create a new passkey by calling navigator.credentials.create().

Not really! It’s one of the biggest misconceptions that one API call is enough. Even though the WebAuthn JavaScript API (called with navigator.credentials.create()) is the simplest component and most straightforward part of any passkeys project, the real complexities arise before and after this API call. If you want to adopt a passkeys-first approach, you need to consider many more things, such as:

- Implementing two backend API endpoints for one simple passkey creation: With WebAuthn you need to call two backend API endpoints with the JavaScript API call from above in between and then receive the response. For new starters, this can be quite complex as the information sent along needs to be in the right order and correctly encoded/formatted.

- Providing fallbacks if passkeys don’t work or the flow is canceled: You need alternative authentication options like email OTP, SMS OTP, social logins, or passwords (if you don’t want to fully go passwordless yet). They are needed in case the device is not passkey-ready or the user deliberately cancels the passkey registration flow.

- Verifying the user to avoid account takeovers: Passkeys can also work without usernames. However, in real-life applications, you need to verify the user and their login identifier (e.g. email address or phone number) to avoid account take-over attacks. In the worst case, someone could simply create a passkey and use your email address as a login identifier (so no verification took place). If the system is designed in such a way that you can use this email address (e.g., through a passkey append flow with an email OTP) to create another passkey on a different device, then an attacker could potentially use the first passkey to log into your account.

- Detecting if passkeys are already stored on the device: It's important to know which devices have passkeys stored and which do not (in order to know where passkey creation/logins can be securely offered to users – more on that later). In the passkey creation case, allowing multiple passkeys per account could lead to major user confusion. We call these decision rules “passkey intelligence”, as logic around passkeys, users, and devices needs to be developed.

- Support cross-device registration and hardware security keys: Do you want to allow the creation of a passkey on a different device from the one you are currently using to access the application? Or do you need to support hardware / FIDO2 security keys (e.g. YubiKeys)? If yes, there are some important things to consider for your implementation, that have an impact on the

PublicKeyCredentialCreationOptionsused innavigator.credentials.create():- Do you want to prioritize cross-device registration/hardware security keys over local passkeys?

- Do you want to offer them as an equal option?

- Do you want to offer them only as a fallback? Should this fallback only be available in logins or also in account sign-ups?

- Adapt the backend and database: Choosing the WebAuthn server (basically a library) is pretty straightforward and so is the installation (e.g.

npm install @simplewebauthn/server). But then the real challenge starts:- How are you going to connect the passkey logic to your system? All passkey detection and passkey intelligence operations (see #2, #11, and #23) are influenced by this decision. The most complex aspect is how to integrate things. Adapting existing flows, taking care of session management, and transitioning existing users to passkey requires adaptations. You need to provide intelligence for passkeys, users, and devices, as well as fallbacks in case of non-passkey-readiness.

- Have you already drafted the credential database table with all the columns, flags, and data types, that work with your database system, your WebAuthn server, and your programming language? If yes, please don’t forget to look at the right encodings (WebAuthn challenges are Base64URL encoded, while public keys are encoded in COSE format and

authenticatorDatais serialized in CBOR). Hopefully, you also have an idea of how to store credential-specific attributes and settings (e.g.transportsinformation orauthenticatorAttachments)? The hard thing is that most of the existing WebAuthn server libraries do not come with the actual credential storage. It needs to be designed and implemented all by yourself (also all relevant credential information needs to be extracted from the WebAuthn responses manually).

- Implementing passkey-specific UX: Creating passkeys is great for UX. But that only counts for the creation process itself when the Face ID modal comes up and the user just scans their face as they do countless times during the day. The challenge lies more often before and after this particular ceremony and requires a lot of additional user flows that need to be implemented:

- Consider when to offer the passkey creation: after every successful login with an existing method. Even after a social login with a Google account?

- What about users who have not verified their email address/phone number? How should they be treated, given that, from a technical point of view, they could create a passkey without any problem?

- Where will users manage their passkeys? Do they use a first-party passkey provider (e.g. iCloud Keychain or Google Password Manager) or a third-party passkey provider (e.g. Dashlane, 1Password, or KeePassXC)? All that affects where passkeys can later be used for logins.

- Should users be allowed to add multiple passkeys per device?

2. Passkeys Logins Are Only About When To Trigger navigator.credentials.get()

Okay, there is more to creating a passkey but to log in with a passkey, I simply call the WebAuthn JavaScript API via navigator.credentials.get(), as the passkey already exists.

Eh nope. It’s the other way around. Outstanding passkey experience during authentication means figuring out when not to start a passkey authentication ceremony in the first place to prevent dead-ends and unnecessary loops. Yes, this can even happen on devices that support passkeys in general if there is no passkey available on this device (see also #3)! Don’t believe us? Then, take a look at the following examples:

- Example 1 “Windows 10 or 11 desktops without Bluetooth”: A user signs up and creates a passkey on their iPhone with iOS 17. Then, the users use their desktop that runs on Windows 11. Although Windows 11 supports passkeys, the computer lacks Bluetooth, which is required for WebAuthn Cross-Device Authentication (CDA) via QR codes (it's a security measure to ensure both devices are in proximity).

- Example 2 “Device-bound passkeys”: Often, workplace computers run on Windows 10 or Windows 11. Passkeys created on these systems are not synced to other devices (device-bound passkeys). Attempts to log in with a passkey on another device will fail because the user does not have an alternative passkey on a mobile device for CDA.

However, the scenario can also be reversed:

- Example 3 “Third-party passkey providers”: Some users might use password managers like 1Password, KeePassXC, or Dashlane, which now also store passkeys as third-party passkey providers across operating systems. If the passkey from example 1 or 2 is stored in one of these password managers, the passkey login should be permitted. Therefore, you need to know where the passkey was created, whether the current device has the password manager installed and active, and if the passkey is synced, to provide a convenient login experience without locking the user out.

To ensure a seamless passkey login experience, it’s essential to be highly certain that the login process will succeed before initiating the passkey login ceremony. This helps avoid false positives (thus, it's necessary to track how often and how a user logs in to influence the decision on which login method to offer), minimizes disruptions, and prevents inefficient authentication loops that could frustrate users and lower conversion rates.

3. Available Passkeys Can Be Detected From the Browser

Okay, I understand that I need to check if a passkey is available before triggering a login. This should be fairly easy with some other browser feature or JavaScript API, right?

Absolutely not. This is a big fallacy – if not the biggest – and it actually causes many of the subsequent fallacies or is related to them. Knowing in advance (before any WebAuthn ceremony starts) whether a passkey is available on a device would be a tremendous help in facilitating the login, as you would then know that there can’t be a mismatch or error in the login process. Without this knowledge, you need to use other factors that help improve the UX and avoid any unexpected failures that disrupt the login experience.

Let’s understand why available passkeys on a device cannot be detected from the browser. Passkeys and the FIDO Alliance, as the driving force behind them, have a strong privacy-by-design mindset. All passkey operations are designed to prevent the identification of users and the revealing of any privacy-related data based on their available passkeys. Only after authentication on the device using fingerprint scanning or Face ID, which is treated as explicitly providing user consent, more information is given. That’s why you can test for passkey-readiness of a device and browser with one of the following methods but it is impossible to directly detect whether a passkey already exists on a specific device prior to any WebAuthn operation:

- Is the device and browser WebAuthn-ready:

PublicKeyCredential - Is the device and browser passkey-ready (platforma-authenticator-ready):

PublicKeyCredential.isUserVerifyingPlatformAuthenticatorAvailable() - Is the device and browser Conditional-UI-ready:

PublicKeyCredential.isConditionalMediationAvailable()

4. User Agents Are Great for Device Recognition

I see that there is no feature to directly detect passkey availability from the browser, so I think I’ll just use the good older user agent to manage devices and passkeys.

Good idea – it might just not work as easily, especially not on all browsers! After reading through the first fallacies, you might consider implementing a proper device management system (in this context called passkey intelligence) to detect where passkeys were created and from where the user might try to log in with a passkey. Building such a passkey intelligence to detect devices in 2024 is not as easy as it used to be:

- User agents are phased out: A robust user-agent parsing library is essential to accurately detect the operating system, browser, and device type (mobile or desktop) from the user-agent HTTP header. Unfortunately, this method remains fully effective only for Safari. All other browsers are about to phase out the user agent soon (or have already done so).

- Chromium’s user-agent reduction initiative: Chromium-based browsers (e.g. Chrome, Edge) and Firefox have significantly reduced the level of detail in their user-agent strings as part of their user-agent reduction initiative (primarily to avoid tracking and protect user privacy). To effectively recognize devices using Chrome, Edge, or Firefox, the usage of client hints (e.g. via

navigator.userAgentData.getHighEntropyValues()) is necessary. This JavaScript API is used for the precise distinction between operating systems and browsers (+ corresponding versions). Note that Safari does not support this API, and also that client hints cannot be retrieved via HTTP headers out-of-the-box.

Consequently, to provide passkey intelligence for all browsers, you need to support both methods (user agent & client hint parsing). Implementing these APIs in your passkey intelligence is a lot of work and don’t forget: devices and browsers update continuously. That’s why you need passkey intelligence that supports updates for operating systems and browsers.

5. An Open Standard Like WebAuthn Is Easy-To-Read

The WebAuthn specification should facilitate the use of secure and simple authentication. Therefore, it will probably be easy to read and understandable.

Nope – unless you are an expert authentication or have a PhD in cyber security. Cryptographic protocols and authentication standards are difficult to read and understand. And so is WebAuthn. There are a lot of complexities to be understood when you want to implement passkeys / WebAuthn. You’ll need a lot of know-how that is not part of the WebAuthn standard. How come? To answer this question, you need to understand the different WebAuthn Levels, especially from a chronological perspective, and that the older ones were written in a time when hardware security keys were the primary method for WebAuthn (and not platform authenticators like Face ID or Windows Hello):

- WebAuthn Level 2 (current version; since April 2021): Passkeys were initially not included in this released version, as the term 'passkeys' and the sync feature were introduced in 2022. There is significant industry effort, especially by the FIDO Alliance, to make the WebAuthn standard in general more passkey-like. As a result, many features have been incorporated into the draft of WebAuthn Level 3, which has not yet been released. But passkeys are already available today, so the WebAuthn level 2 is still the official version. This adds complexity (especially as some aspects are no longer in the passkey era or are redundant, e.g.

requireResidentKeyvs.residentKeyor recommendations regarding the usage of attestation). - WebAuthn Level 3 (expected from the end of 2024 onwards): The WebAuthn Level 3 standard is supported by a wide range of industry players. When the Web Authentication Working Group agrees on a new feature and organizations like Google, Apple, Microsoft, and Mozilla implement this feature in their browsers, it immediately becomes the de facto standard. Usually, the market pressure is significant when Apple (with Safari, iOS, and macOS) and Google (with Chrome and Android) implement the feature, as they control the majority of the desktop and mobile browser market, along with their respective operating systems.

To stay up-to-date with the WebAuthn standard and keep pace with the passkey usability of larger platforms (e.g., Android, iOS, macOS, Windows), it is necessary to monitor a variety of input sources besides the existing (and continuously updated) WebAuthn spec:

- Follow the WebAuthn GitHub issues to anticipate new passkey / WebAuthn features early on and understand why they might or might not be introduced.

- Regularly take a look at WebAuthn Level 3: Editor's draft commits to see how the standard changes

- Check Chromium feature requests and releases to test new features and adapt your auth solution accordingly

- Review Mozilla & Webkit issues to test new features and understand browser behavior

As the passkey / WebAuthn ecosystem is highly heterogeneous, the standard is interpreted and implemented differently. Therefore, depending on the WebAuthn server library used, you need to handle various WebAuthn levels in your ceremonies. Since new passkeys are continuously being developed, it’s almost certain that there will be new changes in the future, which will further complicate matters. To feel this heterogeneity and complexity yourself, feel free to research the following topics in the context of WebAuthn and check the corresponding discussions:

- Passkeys themselves (especially the sync feature)

- Conditional UI

supplementalPubKeys- PublicKeyCredentialHints (to deprecate AuthenticatorAttachment)

6. Passkey Management UI Is Easy-To-Build

Building a passkey management UI and the corresponding functionality to create, edit, and delete passkeys should be rather simple.

Yes and no – while building a passkey management UI isn’t too hard there are some things that are rather counter-intuitive. Industry best practice for managing passkeys is to list all available passkeys for a user in the account settings. Thanks to resources like passkeys.dev, having access to a comprehensive list of passkey providers with logos and names is straightforward. It can be used to display passkey-provider-specific information for a passkey. However, managing passkeys involves more:

- Exclude credentials when adding passkeys: When offering an “Add passkey” button in the account settings, the

excludeCredentialsproperty inPublicKeyCredentialRequestOptionmust be used correctly to prevent mismatches between the user's passkeys on the client side on their device and those stored server-side in the backend. - Deleting passkeys server-side could lead to confusion: Deleting a passkey in the account settings (server-side) is more complex. A good UI typically includes a delete button for each listed passkey. When a passkey is deleted server-side, it remains on the client side (on the device). The user might still attempt to log in with it, which is problematic. The passkey should be flagged as deleted on the server-side. Additionally, to prevent future confusion, the

AllowCredentialslist of thePublicKeyCredentialRequestOptionsin the authentication ceremony should not be left blank if a passkey was deleted server-side. Instead,AllowCredentialsshould be filled with all passkeys except the deleted ones. Implementing such a logic requires intelligent passkey management on the server side.

In general, I have often received questions about whether the AllowCredentials list should be left empty or filled with credentials. The answer depends on the specific security and operational needs:

- Empty

AllowCredentials: This approach avoids credential enumeration, reducing the risk of exposing user information to attackers. It also maximizes the available options for the user, as it allows any stored credential to be used for authentication. - Filled

AllowCredentials: Filling theAllowCredentialslist with credentials enables the backend to filter out deleted passkeys. This is especially useful in scenarios where the user identifier is known when the WebAuthn login ceremony starts (thus not possible in usernameless login scenarios). This allows the system to list only those passkeys that match this identifier and are not deleted. This targeted approach enhances security by restricting the authentication process to specific credentials.

As you see, there is no clear answer to this question and you need to decide based on your specific requirements.

7. Passkeys Are New but Common Use Cases Are Well Supported

Even though passkeys are new, they are backed by some of the most UX-oriented companies, so the most common use cases for supporting passkey authentication should be well-supported.

Yes, passkeys are a relatively new technology, and while they effectively support the most important use cases, particularly the plain sign-up and login process, and rise in adoption, they fall short on other common real-life cases:

Use Case 1: Deleting a Passkey on the Device (Client-Side)

If the user decides to locally delete the passkey on their device, the server never receives the information that this passkey cannot be used anymore. This could lead to serious friction:

- Passkey login fails completely: Let’s assume the following scenario: a user has deleted their passkey on a Windows 11 computer using Chrome. Passkey intelligence might recognize the device as a known Windows 11 system and incorrectly assume the passkey is still present and accessible. However, the authentication process will inevitably fail because the passkey (private key) no longer exists on the device. The user will then need to rely on a fallback method. To address this issue, passkey intelligence should be capable of detecting when a passkey is repeatedly used for authentication attempts but never successfully, suggesting it is likely inactive or has been deleted.

- Confusing QR codes in CDA scenarios: In this scenario, if a user, for example, deletes their mobile phone passkey from their iPhone (CDA authenticator), passkey intelligence may continue to try Cross-Device Authentication via QR code, operating under the assumption that the passkey locally still exists. This leads to the generation of erroneous QR codes, further complicating the situation.

This issue is becoming increasingly prevalent due to the passkey management UIs for deleting passkeys introduced by Apple, Android, and Microsoft. As such, the case, where the local passkey is missing, can arise unexpectedly and significantly disrupt the user experience. To mitigate this, the passkey intelligence should automatically detect such situations through analysis of user behavior.

Use Case 2: Automatic Transition From Password-Based To Passkey-Based Accounts

Currently, there is no fully standardized method for signaling that a website supports passkeys, which would enable password managers to automatically transition password-based accounts into passkey-based accounts. However, Google Password Manager supports an initial implementation, which should be closely monitored and integrated into the passkey authentication solution as soon as it gets broader support.

Use Case 3: Change Passkey-Associated Metadata

When a passkey is created, the following metadata is associated with the passkey and stored on the client:

- user.name: Serves as a visible login identifier, typically an email address, phone number, or username.

- user.displayName: Represents the readable name of the user, used to personalize the Conditional UI and the passkey modal experience for users.

This metadata is very helpful for users to distinguish different accounts and passkeys on a device. However, there is a crucial aspect missing: When a user changes any of this information today, it cannot be reliably updated across all associated passkeys.

While user.name and user.displayName play an important role in providing a good UX, there’s one other, less documented WebAuthn field that causes more issues in the login process, when there is a change: user.id. This field stores the actual primary account identifier (i.e., the ID that identifies the user account in your user database). Consequently, the following situation could occur: a user changes their email address (user.id) from old.mail@gmail.com to new.mail@gmail.com in the account settings. Then, the user provides the new email address in the email input field new.mail@gmail.com, triggering a passkey login ceremony linked to the old email old.mail@gmail.com, as the passkey still has the old email stored (also in a usernameless scenario, the user would still see the old email address in the passkey autofill dropdown). Yet, access is granted (even though from a UX perspective it’s not obvious why the old email address still works for WebAuthn logins). Therefore, it's important to carefully manage how database lookups are performed.

user.name, user.displayName, user.id, response.userHandle, and CredentialID can be major sources of confusion and errors if not thoroughly understood at the beginning of your passkey implementation.

While these three use cases may be less relevant for smaller user bases, they become increasingly common as the user base grows, particularly where unused passkeys pose challenges for passkey intelligence operations (see #2).

8. Passkey UX/UI Is Great and Predefined

Okay, I get it: developing passkey authentication is technically complex, but once it's implemented, the process becomes quite straightforward, right?

- Passkey icon: The good news is the FIDO alliance has created an icon for you.

- Product management decisions: As in any other project, where UX plays an important role (and authentication is probably one the most crucial ones in regard to UX), the product management team wants to provide significant input. The most common questions from a product management perspective are:

- Which devices to support?: What kind of devices can we expect among our users? How high will the coverage of passkey-ready devices be? To answer these questions, we recommend any organization to start analyzing the passkey-readiness of their user base’s devices prior to any passkey launch.

- When and how should users be verified?: If you are considering a passkey-first approach, do you plan to verify the email or phone number associated with the passkeys at sign-up, on first login, or never?

- Which mockups do we need to provide?: Expect that you will need specific mockups for passkey-related flows:

- Sign up via passkeys or via the fallback method (e.g. email OTP)

- Login via passkeys or via a fallback method (e.g. email OTP)

- Offer to add passkeys after fallback-login on new devices

- Create understandable error messages

- Design a user-friendly passkey management UI

- UX/UI best practices: To provide a really appealing passkey UX/UI, a few more things need to be considered before the rollout:

- Define a passkey introduction strategy: Considering your user base, how do you plan to announce and introduce passkeys? Options include an explanatory page, email communications, pop-up notifications, or push notifications. We’ve seen a great variety of approaches here.

- Facilitate transition to passkeys: There’s a lack of best practices on how you can nudge your users, especially non-technical ones, to transition to passkeys, so you need to come up with your own strategies and flows.

- Look for UI recommendations: Choose your best practices from a wide list of partially contradicting guidelines:

- FIDO alliance

- web.dev

- Real-world examples (e.g. Kayak, Amazon, GitHub)

- Define fallback strategy: How are you handling passkey errors? Are you going to immediately trigger fallback authentication or do you allow re-tries?

- Handle errors and provide troubleshooting guidance: Have you ever considered what happens when a user is on a modern iPhone with the latest browser but hasn't activated the iCloud Keychain? From the JavaScript API calls in the browser, the passkey intelligence would detect that the device is passkey-ready, but once the user starts the passkey registration ceremony, an error message will pop up instructing the user to activate the Keychain. This could be an error screen that they have never seen before, potentially causing confusion. Developing proper error handling and providing fallbacks for these scenarios is crucial.

In conclusion, while passkeys are technically complex to implement, do not underestimate the effort required to address various product management aspects.

9. Conditional UI Always Ensures a Smooth Login Experience

I love Conditional UI as it’s the most seamless login I’ve ever seen. I don’t even need to provide a username anymore and it works so smoothly on supported devices.

Indeed, Conditional UI provides one of the smoothest login experiences. There are however some things to consider or even improve on top. In general, one of the best things about passkeys is that the user does not need to explicitly come up and memorize passwords anymore. Passkeys are automatically saved by the operating system (or by a third-party passkey provider like 1Password, KeePassXC, or Dashlane) from where they can be used in any future login attempt. Generally, with passkeys, there are three modes to log in:

-

Regular passkey login with WebAuthn modal (after asking for login identifier first): Calling the WebAuthn

startLogin()backend API to initiate a regular passkey login is the way to go if the user enters their identifier first and clicks on a submit button. This allows for preliminary checks to determine if the user exists and to assess if passkeys exist and are accessible via passkey intelligence. If the user exists but cannot use passkeys, a fallback method is immediately triggered. Passkey intelligence should then stop the WebAuthn login process before the authenticator modal appears. Otherwise, the regular WebAuthn login process is executed.

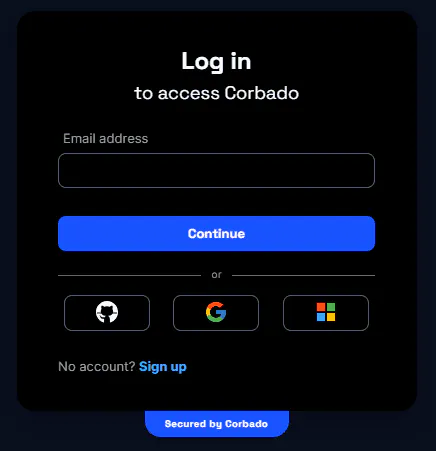

Regular passkey login

Regular passkey login

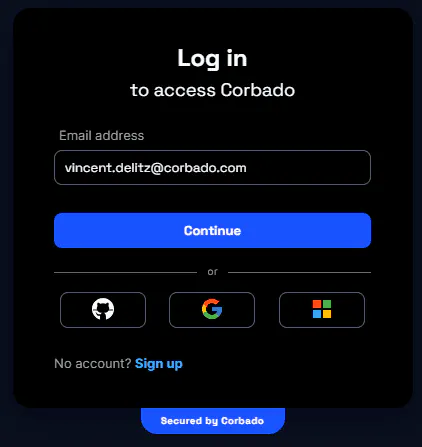

Regular passkey login with filled email address

Regular passkey login with filled email address

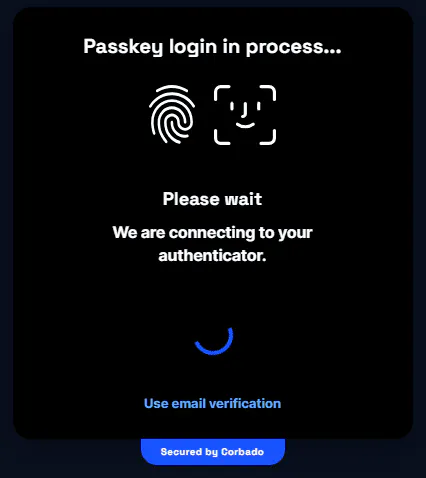

Connect to the authenticator for login

Connect to the authenticator for login

-

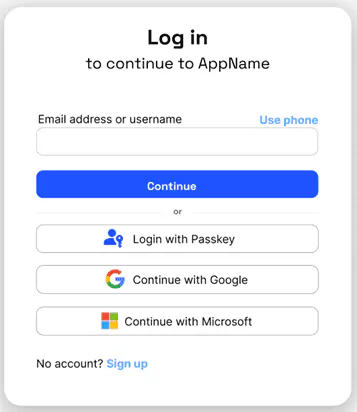

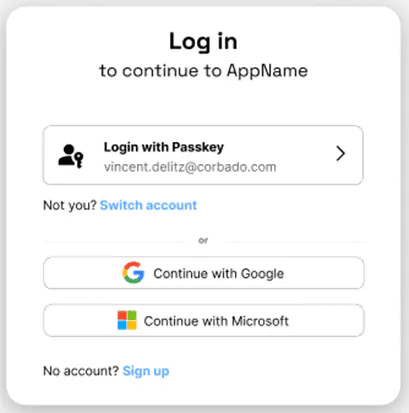

Passkey login button (on top level): Sometimes, we see implementations that are not passkey-first (because passwords are presented as an equally viable option). This often involves a layout where users must actively click on a 'Login with Passkey' button. We recommend this approach only when a large existing user base is gradually transitioning to passkeys and the current authentication flow should not be disrupted. However, the downside is clear: users who have not set up passkeys may be confused.

- Conditional UI Login: Conditional UI, also known as usernameless login, behaves differently depending on the operating system. For example, Safari on iOS might display a modal suggesting the last used passkey, while Chrome on Windows shows a dropdown of all available passkeys for immediate login. These dropdowns are initiated with the

navigator.credentials.get()call, using the ‘mediation: “conditional”’ flag:

// Availability of `window.PublicKeyCredential` means WebAuthn is usable.

if (

window.PublicKeyCredential &&

PublicKeyCredential.isConditionalMediationAvailable

) {

// Check if conditional mediation is available.

const isCMA = await PublicKeyCredential.isConditionalMediationAvailable();

if (isCMA) {

// Call WebAuthn authentication

const publicKeyCredentialRequestOptions = {

// Server generated challenge

challenge: ****,

// The same RP ID as used during registration

rpId: "example.com",

};

const credential = await navigator.credentials.get({

publicKey: publicKeyCredentialRequestOptions,

signal: abortController.signal,

// Specify 'conditional' to activate conditional UI

mediation: "conditional",

});

}

}In the source code sample above, no username is transmitted initially. The WebAuthn server simply creates a challenge. If the user selects an account from the Conditional UI list, the browser signs the challenge. The assertion includes the user.id (as response.userHandle) and the private key is used to sign the challenge. The backend then verifies the challenge and logs in to the correct account.

Well, seeing these different login options sounds very promising so far, but there are some caveats. From our user testing and funnel analysis of passkeys, we've observed that passkey modals/popups sometimes interfere with user interactions. Users might abort the automatically initiated modals/popups, and moreover, Conditional UI is not supported on all platforms. Therefore, we recommend leveraging LocalStorage information to optimize the passkey login experience:

- Store recently used passkey hints in

LocalStorage: Storing information about recently used passkeys (e.g. credential IDs and login identifiers) can help to optimize user experience. This information can also be leveraged as input to the passkey intelligence (further improving: #2). Users can log in to a 'recently accessed' account with a single click, bypassing dropdowns or modals. If the user wishes to access a different account, the UI then switches to Conditional UI.

The information displayed can be increasingly precise: For example, if a mobile device was used for Cross-Device Authentication, this detail could be included in the message to guide the user to the correct device.

By the way, I read an extensive article here on DZone about ConditionalUI.

Feel free to check it out here.

10. Passkeys Work in All Browsers as Expected

As passkeys are supported by all major browsers, the behavior and UX should be the same everywhere.

Well no. In general, for passkeys to work, there are two different things to consider:

- Available passkeys on the login device: The operating system and the browser must support passkeys (moreover the different versions of the operating system and browser play an important role). This can be detected using

PublicKeyCredential.isUserVerifyingPlatformAuthenticatorAvailable(). - Passkeys in cross-device authentication or registration: Support from the operating system or browser for Cross-Device Authentication is required. Unfortunately, this cannot be detected with

PublicKeyCredential.isUserVerifyingPlatformAuthenticatorAvailable(). It may erroneously return false for devices that are capable of proceeding with Cross-Device Authentication (CDA). You also need to check for Bluetooth availability (e.g.Bluetooth.getAvailability()- note that even if this function returns true, it does not imply that Bluetooth is activated currently) and provide the rightPublicKeyCredentialRequestOptionsfor the WebAuthn server (both of which can hold their own problems) – see #4 for more details.

While the UI for biometric authentication modals in the operating system cannot be altered, browsers have implemented dialogs that appear before these operating system UIs. These dialogs vary based on your WebAuthn server settings (especially for authenticatorAttachment). Consider the following cross-device (and simultaneously cross-platform) example where you want to use an Android to log into a MacBook. Besides, hardware security keys (e.g. YubiKeys) could be used. Therefore, we define the following WebAuthn server settings:

"authenticatorSelection": {

"residentKey": "required",

"requireResidentKey": true,

"userVerification": "required",

"authenticatorAttachment": "platform"

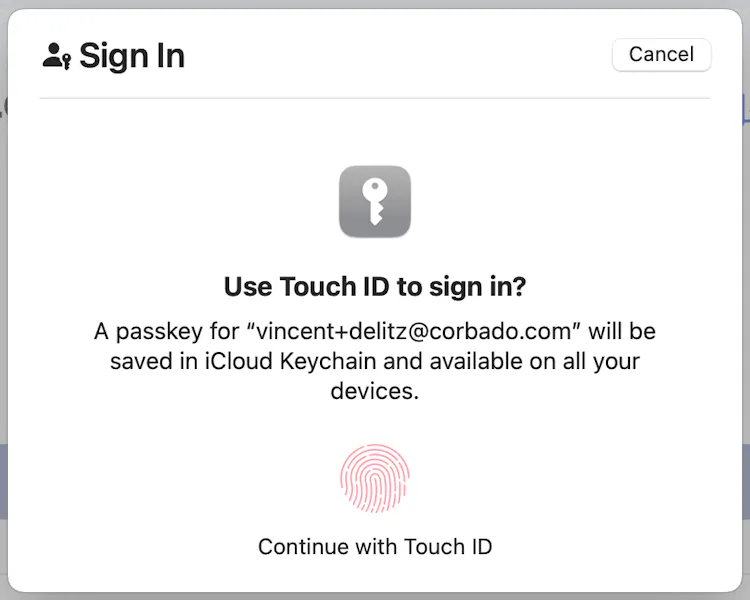

}The user interfaces vary significantly for these WebAuthn server settings, as illustrated in the following screenshots. For example, Safari (first screenshot) streamlines the process of creating passkeys by presenting a clear path, with a subtle hint for additional options at the bottom. Consequently, most users are likely to use Touch ID right away to proceed.

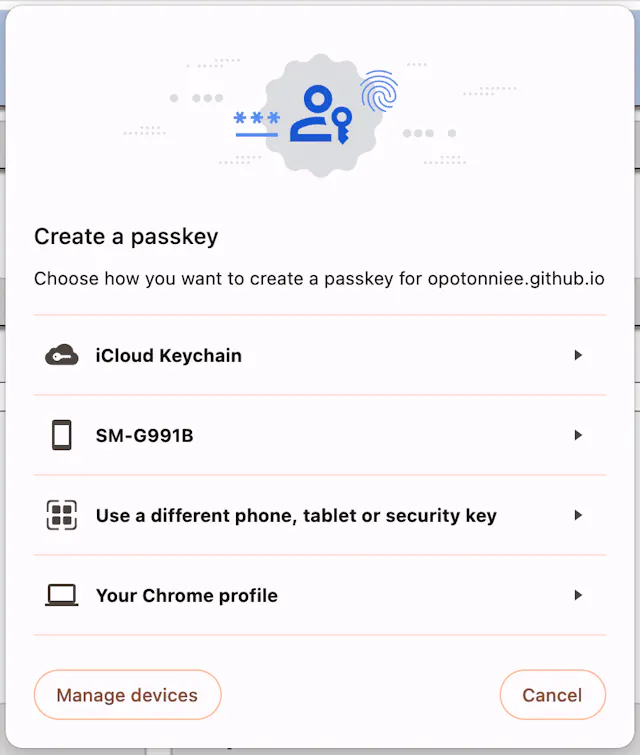

In contrast, Chrome (second screenshot) displays a dialog that might be complex to understand for inexperienced users, as you can decide between “iCloud Keychain” (the first-party passkey provider), “S21 von Vincent” (a stored device), “Other smartphone, other table or another security key” (CDA or hardware security key) or “My Chrome Profile”. On top of that, there’s a button on the bottom left to “Manage Devices” which even increases the number of clickable options for the user. Where should a non-technical user click to log in the most seamless way?

When building your passkey experience, all different browsers as well as all operating systems and platforms have to be kept in mind. Most importantly, you need to also take operating systems and browsers into consideration that do not (fully) support passkeys (e.g. Linux, ChromeOS, and older versions of Firefox).

Moreover, one might expect that browser support for passkeys will increase over time, leading many current problems to resolve naturally. However, what we have witnessed is somewhat different. While most users (depending on their devices and technical savviness) will see improvements, support must also continue for those using older browsers on outdated devices. This situation only complicates things, as newer versions introduce advanced passkey features. Still, the most crucial aspect is ensuring that every user enjoys a superior login experience with passkeys compared to traditional password-based methods.

After Hearing All That: Why Should You Implement Passkeys Anyway?

Okay, after reading the article, I think I’ll stick with my current password-based auth solution and not implement passkeys, as it seems like too much implementation work.

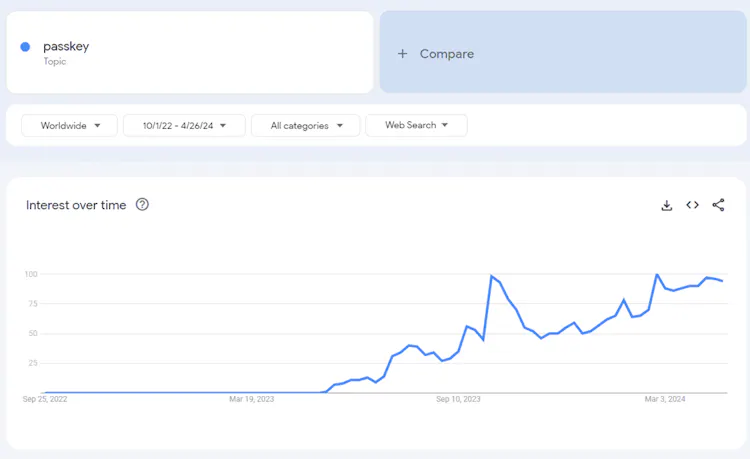

I understand the challenges that come with rapidly evolving technology and the introduction of new features. However, rest assured, you'll get this. Passkeys are set to become the most popular login method shortly. Once consumers experience the speed and simplicity of using passkeys, there’s no turning back. The demand for passkeys and biometric authentication is only expected to grow as more people realize their immediate benefits (refer to the Google Trends screenshot below—the significant spike occurred when Google made passkeys the default login method for all their accounts in May 2023). I often joke that passkeys are like a drug – once you've experienced them, you don't want to go back to using passwords.

Moreover, most consumers cannot tell the difference between websites/apps secured with local biometric authentication (e.g., Face ID) and those protected with passkeys (when explaining passkeys to friends, no matter how technical their background, they often mention that this isn’t a new feature because their iCloud Keychain has had such a biometric feature to log them in automatically on websites and apps for several years). I have to admit: both methods – passkeys and local biometric authentication – seem similar and instinctively natural to users. That’s also why I strongly believe that it's only a matter of time before companies without passkey capabilities will seem outdated. Just think of:

- Stationery shops that don't support Apple / Google Pay

- People using SMS instead of messenger apps like WhatsApp or Telegram

- People unlocking their smartphones with a password instead of a biometrics / PIN pattern

Ultimately, consumers drive market changes, and they are clearly signaling that passkeys are the future.

I hope that I helped you already with my article, otherwise, you can check out my blog for more articles and insights about the world of passkeys. You can also read my other article here on DZone about implementing ConditionalUI.

Let's implement passkeys and make the internet a safer place!

Published at DZone with permission of Vincent Delitz. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments