Using HTTPS to Secure Your Websites: An Intro to Web Security

It's the post that every developer has been waiting for. All the questions you were too afraid to ask but are pivotally important to know the answers to regarding web security.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeMore and more sites are switching to HTTPS. And with good reason! Security is essential in today's complex web ecosystem: logins, online payment systems, and personal user information are all waiting to be poached by criminals. In this short article we will go over what HTTPS is, how it is implemented, what it is useful for (and for what it is not) and how you can enable it in your own sites. Read on!

Introduction: the Importance of Online Encryption

Have you ever watched an old spy film and felt shocked at how easy it was to learn a VIP's itinerary by wiretapping a landline? Now take that to a global level with the Internet. Scared yet? Although the example may seem simplistic, in a very real sense it is not: it is totally possible to wiretap an Ethernet, WiFi or cellular connection. And, as was in the case of old landlines, this is even possible with consumer grade equipment. Spies do not need "spy stuff" to do their job.

As the web was conceived, security was not the most important concern. People cared about sharing. Other matters took second place as the web was developed.

(...) physicists from around the world needed to share data, yet they lacked common machines and any shared presentation software. - History of the World Wide Web, Wikipedia

But things are not how they used to be. What started as a simple login screen to access protected content has now turned into financial operations, personal information and even a matter of national security.

So how does HTTPS enter the picture? It is important to understand what HTTP does and what it does not. HTTP was conceived as a means to transfer information on the Internet. Protecting such information is not its job. The HTTP authentication spec (RFC 7235) hints at this:

The HTTP authentication framework does not define a single mechanism for maintaining the confidentiality of credentials (...) - RFC 7235

Authentication is one of those tasks that requires strict security considerations. Even though the HTTP authentication spec defines a series of mechanisms to identify users and parties (via credentials), it does not specify how to securely share that information.

Personal Information and Online Tracking

If unencrypted HTTP connections expose data as wiretapped landlines do, it is of no surprise that such data can be used to build profiles of the users who use and create that data. This is known as online tracking. Have you ever looked at flight prices for a potential future trip only to find, a few minutes later, ads in other pages talking about flights to that destination? This might seem convenient. After all, this could actually point you in the direction of a discount. However this should also make you wonder: what other data am I unknowingly giving others?

Ad companies have built whole enterprises from harvesting and then selling this information. The unencrypted web has expanded a market that used to operate in the shadows: buying and selling personal information.

Encrypting communications does not specifically fix this in any way. After all, even if data is encrypted between a third party and yourself, what's there to stop that third party from using the information you are sharing with them? This is actually Facebook's and Google's biggest business. And they do use HTTPS. However, encrypting data helps in a critical way: it gives the power back to the user. It should be him or her who chooses with whom to share data. This is the basis of encrypted communications: establishing a notion of identity between two parties and then allowing those parties to securely share information between them. This is, in a way, what HTTPS adds to HTTP.

HTTPS helps greatly in reducing the information leaked to third parties. However, it does not prevent tracking. Modern browser fingerprinting techniques work even behind HTTPS. Security researchers have developed a browser extension called HTTPS Everywhere that attempts to use HTTPS whenever possible and at the same time mitigate the use of fingerprinting techniques. The recently released Brave browser, a fork of Chromium, is designed with privacy as one of its top concerns.

EFF's Panopticlick tool can give you a sense of how modern fingerprinting techniques can track you. This is in spite of the use of HTTPS.

HTTPS and Logins

Encrypted communications are essential to logins. If a third-party can sniff your credentials, then they can pose as you. You might be thinking this is a rather unusual occurrence. After all, someone needs to tap into your Internet connection to do this. And, if you are still picturing a spy doing this by physically cutting a few wires, you are wrong. Unlike telephone lines, the Internet is not built in a star shaped topology. All data must go through a series of third-party servers to reach its destination. Any man-in-the-middle could then easily capture your credentials if data weren't encrypted. Unsurprisingly, this is known as a man in the middle (MitM) attack, and HTTPS actually makes it very hard to accomplish (though not impossible).

Want to take a look at how your data travels through the net? Run this from the terminal:

# On Linux or OS X

$ traceroute www.google.com

# On Windows

$ tracert www.google.com

Pick different destinations. You will note that more hops are usually needed to reach servers farther away. Any of these servers could sniff on unencrypted data sent through them. In fact, shadow hops may be present and not shown in the results. The only real way of being sure is by establishing a notion of identity between communicating parties and then encrypting the data sent between them.

Post-Login Data and API Calls

If you are familiar with web systems architecture, you know once a user is authenticated (identity is established), any future transfers may need to be encrypted as well. If HTTPS is needed to make sure credentials are not leaked, it should be of no surprise that any other data transferred through the same medium may need to be encrypted as well. Ultimately it is up to you, the developer, to choose what data must never be exposed. One thing is sure: 99% percent of the time, the less data is available in the clear, the better. Using HTTPS for all transfers is a correct and viable solution. This includes API calls between a client and your service gateway.

Proper security in the modern web is not limited to just encrypting communications. Once data has reached its destination, proper steps must be taken to safely handle it. A sadly common example is how many web sites store passwords: how many times have you read of a major player being hacked and plain-text passwords being exposed? Surely more than one would hope. (Note: passwords must never be stored as plain-text, for this very same reason). Security and encryption are hard. Proper and tried practices are available for each level in a secure architecture. Be sure to follow them, and, as a general rule, do not role your own, internally developed encryption; use an existing, tried and tested solution.

The Magic Behind HTTPS: Public-Key Cryptography and TLS/SSL

HTTP is simple: a header with only a few mandatory fields and (usually, but not required) a body of content. Communications using HTTP as basis rely on an underlying protocol handling lower level details. In the case of the World Wide Web, this other protocol is TCP/IP. Although the WWW's architecture can be rather complex to sum up, what you need to keep in mind is that TCP/IP handles routing, data integrity and provides delivery guarantees, while HTTP defines a way for two clients to interpret what to do with the data that is sent (How long is it? Are we requesting data or pushing data? Etc.). As you can see, no part of this stack handles data protection.

In the mid 90s, HTTPS was developed to overcome this shortcoming. In contrast to its name, HTTPS does not actually change anything from the HTTP spec. Rather, it adds a new layer between TCP/IP and HTTP: TLS (or SSL as it was called back then). TLS stands for Transport Layer Security, while SSL stands for Secure Sockets Layer.

Conceptually, HTTP/TLS is very simple. Simply use HTTP over TLS precisely as you would use HTTP over TCP. - RFC 2818, section 2

This new layer performs two important tasks:

- Establishes mutual or partial identity between the client and the server.

- Encrypts all data passed between the client and the server.

Partial identity refers to the case where the client can be sure it is communicating with the expected server and no one else. Mutual identity extends this to the case where the server can also be sure it is communicating with a specific client. For the most part, current web communications only require partial identity (client identification is usually left to other layers of the architecture).

All of this magic is possible through the use of public-key cryptography. If you are not familiar with this concept, public-key cryptography allows for a very particular way of encrypting information: there are two keys, a public key and a private one. The public one can be used to encrypt information but not decrypt it. The private one can be used for both encryption and decryption. With this in place, it is possible for a party (or several parties) to encrypt data that can only be decrypted by the party holding the private key. So, if you were to create a site to which you wanted to let users access safely (preventing MitM attacks or any sniffing), a potential way of doing this would be by providing each client with your public-key, so that when they wanted to request data from you, they could encrypt this request using your public key. Furthermore, in their initial request, they could send their public keys, so that you could safely reply back. Bam! You now have a secure channel.

Note: this is not the actual key exchange process used in TLS or SSL, but rather a simple example of how these concepts are applied.

One important consideration about public-key cryptography (a.k.a. asymmetric cryptography) is that it is computationally expensive. Certain important numbers that are part of the encryption algorithm must be very big to provide the necessary security (2048-bit numbers are the norm). In practice, to overcome this difficulty, once an encrypted two-way communication is established, a random secret key is generated and then shared between the server and the client. This enables symmetric encryption algorithms to be used instead (typically AES). These are much easier on the hardware.

Newer hardware supports accelerated AES encryption. This results in high throughput and very low power requirements for AES.

Certificates, Certificate Authorities and Intermediate Certificates

You may have already figured this out by yourself, but there is one big problem with both symmetric and asymmetric encryption algorithms: they both rely on sharing something. Think for a moment: if you want to make sure you are communicating with a very specific individual (let's say Gmail's web server), you need to have some prior knowledge about it: its public key. In the case of symmetric encryption things are similar: both client and server need to know the shared secret. Without this knowledge it is impossible to establish a secure connection: if a malicious user were to sit in the middle of two parties using any of these schemes, he or she would be able to impersonate any of them by simply replacing both public keys with his or her own (or just taking note of the shared key in the case of symmetric encryption). In other words, to establish a secure connection, either a preexisting secure channel must exist, or some data must have been shared securely in the past. There are two ways of dealing with this problem for asymmetric encryption systems: public-key infrastructure and the web of trust.

Off Topic: Web of Trust

Although not relevant for HTTPS, we will briefly mention what a web of trust is. Public-key cryptography can be used in any context, not just the web. In the case of users or organizations wanting to share data securely, one way of achieving this is by letting others know their (the users'/organizations') public key. Of course, without some grade of certainty in the authenticity of a public key, its use is fruitless. A web of trust attempts to give public keys a certain level of authenticity by having groups of trusted users sign each other's keys in what is known as signing parties. In other words, if you trust a certain user A's public key, and that user has signed user B's public key, then you, by trusting user A, can be sure (up to a certain point) that B's public key is authentic. In other words, webs of trust delegate key validation to users that are trusted beforehand. The way this prior trust is established is an implementation detail and is, in essence, what determines how trustworthy keys are.

The more a certain key is signed by trusted parties, the more one can be sure of its authenticity. So, how are keys initially trusted in practice? Most of the time, by physically performing the signing process in person. It is up to an individual, group or organization to define the scheme that can be used to establish initial validity of a key. Although flexible, this scheme requires caution and intelligent use.

Public-Key Infrastructure

On the other hand, public-key infrastructure is much more rigid. Instead of signing parties and different levels of trust, in public-key infrastructure there are a group of certificate authorities that have the ultimate vetting and verification power. These authorities are trusted to perform some sort of validation of others' keys. This trust is implicit and ultimate: if a certificate authority trusts something, then so do you. This is the model implemented and used in the web: a handful of certificate authorities' certificates are preinstalled in your system (either by the OS or your browser). These authorities' certificates are then used to validate other certificates that embed a certain website's public key. Some important certificate authorities are Comodo, Symantec, GoDaddy, GlobalSign, DigiCert and StartCom.

Have you noticed there is an implicit step of trust being performed in this case? It is you, the end user, who is performing this step when installing a new web browser or a new OS. YOU are trusting that whatever certificates are installed by it are valid. If they were tampered in any way before you downloaded them, you could be giving a malicious party the keys to your kingdom. This is why downloading browsers and OS install media from reputable sources is essential.

We are using the word "certificate" here rather than "public-key" because public-key infrastructure defines a series of data formats which can be used to encode public-keys along with metadata. This combination of keys and additional data is known as a certificate.

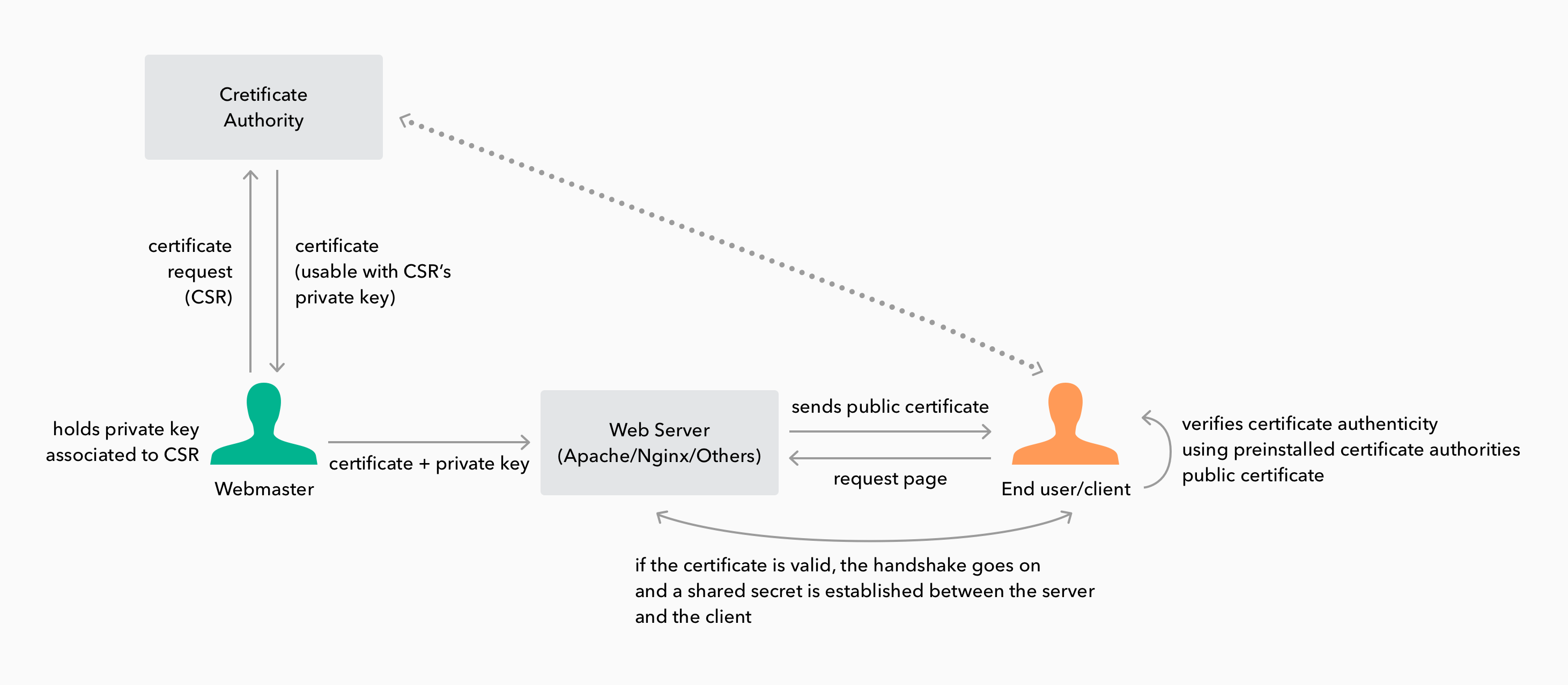

So how is it that web pages get their own certificate? The process usually entails contacting a certificate authority. In the case of the web, most sites require some sort of domain validation. Each certificate authority defines their own process to perform this validation. Once the authority has validated the domain, they issue a certificate to you, the owner of the domain. This certificate is digitally signed by the certificate authorities' private key. The certificate given to you comes in the form of a public certificate and a private key. It is this combination of certificate + private key that a web administrator sets up server side. In turn, the public certificate is given to anyone who wants to connect securely to the site (for instance, when you connect to https://www.google.com for the first time, Google's public certificate is sent to your browser for validation). As the public certificate is signed by a known authority, even when the certificate travels through an insecure medium, any client can confirm its authenticity by checking the certificate authority's signature (this requires having the certificate authority's public certificate preinstalled in the client's system). If a public certificate is signed by an unknown authority, then the validation fails. It is for this reason that becoming a certificate authority is a complex matter. To be an useful authority you need to be recognized by OS vendors and browser developers, so that they bundle your public certificates with their products.

In practice, certificate authorities do not sign user certificates with their root certificate. Instead, intermediate certificate are the norm. These certificates are also generated by the certificate authority and are used exclusively for signing other certificates. In turn, these intermediate certificates are directly signed by the root certificate. This gives public key infrastructure more resilience to certificate leaks: if an intermediate certificate's private key is exposed, only certificates signed by it need to be revoked, not every certificate signed by the certificate authority. This group of certificates, the user certificate, the intermediate certificate, and the root certificate are known as the certificate chain.

Example: setting up Nginx, Apache and Node.js servers with TLS

Once you have your own TLS certificate and private key, it is time to use them in your public servers. Here is how:

Nginx

Download your domain certificate and private key from your certificate authority's site. If your certificate authority uses intermediate certificates (most do), you will also need them. These are usually provided as a download by them. Certificates should be in PEM format (which is the norm). If they are not, OpenSSL can convert between many different formats. Be aware that online converters are not a good idea (you don't want to give your private key to anyone!).

If you have your certificate and an intermediate certificate as separate files, first you need to combine them. Fortunately, the PEM format supports combination by concatenation:

cat your_domain_certificate.pem intermediate_certificate.pem >> bundle.pem

Note that we are only combining the certificates. The private key MUST NOT be combined with them.

Nginx can manage multiple domains from a single server. Each domain can have their own server block. Server blocks look like this:

server {

listen 443;

ssl on;

ssl_certificate /etc/ssl/bundle.pem;

ssl_certificate_key /etc/ssl/private_key.key;

ssl_protocols TLSv1 TLSv1.1 TLSv1.2;

server_name your.domain.com;

access_log /var/log/nginx/nginx.vhost.access.log;

error_log /var/log/nginx/nginx.vhost.error.log;

location / {

root /srv/www/public_html/your.domain.com/;

index index.html;

}

}

As you can see, just pointing the server block to right certificate bundle plus private key is enough. Don't forget to set the server on port 443, the norm for TLS.

Apache

Just as happens for Nginx, Apache also requires certificates in PEM format. So combine them as shown for Nginx and then open your Apache configuration file:

LoadModule ssl_module modules/mod_ssl.so

Listen 443

<VirtualHost *:443>

ServerName www.example.com

SSLEngine on

SSLCertificateFile "/etc/ssl/bundle.pem"

SSLCertificateKeyFile "/etc/ssl/private_key.key"

SSLProtocol All -SSLv2 -SSLv3

</VirtualHost>

You are encouraged to read the Apache docs to learn additional options that may be useful (such as disabling weak ciphers).

Node.js

There are many servers for Node.js. Most of them piggyback on Node's own HTTP server implementation. Fortunately, Node's HTTP server supports TLS:

const https = require('https');

const fs = require('fs');

const options = {

cert: fs.readFileSync('/etc/ssl/bundle.pem'),

key: fs.readFileSync('/etc/ssl/private_key.key')

};

https.createServer(options, (req, res) => {

res.writeHead(200);

res.end('hello world\n');

}).listen(443);

Express.js, a popular Node.js server library, supports setting TLS certificates through this same call:

var fs = require('fs'),

https = require('https'),

express = require('express'),

app = express();

https.createServer({

cert: fs.readFileSync('/etc/ssl/bundle.pem'),

key: fs.readFileSync('/etc/ssl/private_key.key')

}, app).listen(443);

app.get('/', function (req, res) {

res.writeHead(200);

res.end('hello world\n');

});

You may have noticed we disabled SSL version 3 in both Apache and Nginx config examples. This is because of the POODLE attack, a vulnerability in SSL. Fortunately this vulnerability does not work in TLS, so all that is needed to prevent it is disabling SSL. Node.js has disabled SSL by default since version 0.10.33. So, unless you are running a really old version of Node, you are already protected against POODLE.

Aside: TLS at Auth0

As a security conscious company, we use TLS everywhere at Auth0. Not only secure transports are essential for logins, single-sign-on and other features we provide (those JWTs need to be safely passed to your users!), but it is also essential for privacy. You will find even our public docs are TLS-enabled. You can be sure no man-in-the-middle is showing you bad info on how to set up our product. And this is important: what if you gave a malicious user access to your login system? TLS is easy to set up. There is no excuse for not having it available everywhere.

Interested in our product? Sign up for free and start using it today!

Conclusion

If I had to sum this article up in two words they would be: HTTPS Everywhere. Cryptography might be hard, but setting up a TLS enabled server is not. The services are out there, free certificates are available, paid ones are not that expensive, and every single relevant software stack out there supports TLS. There is just no excuse for leaving your users exposed to privacy and security issues by using an insecure transport. Obviously, HTTPS is just the tip of the iceberg. Security is hard, and so is designing secure systems. HTTPS helps, so enable it today. Your users will thank you for it.

Published at DZone with permission of Sebasti%|-1584275889_1|%n Peyrott, DZone MVB. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments