Styles of Software Architecture

This article summarizes the different styles of software architecture categorized as monolithic or distributed.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeI recently started studying styles of software architecture in different ways: by reading books by renowned architects and by trying to go a step further in my professional career. I have seen how different it is to be an architect from a developer; although these two roles have many points in common, the approach is different.

I don't want to describe what it means to be a software architect in this article. I will summarize what I have been reading and learning about the different styles of software architecture categorized as monolithic or distributed.

Monolithic vs. Distributed Definitions

When we talk about a monolithic or distributed architecture, we are referring to the type of deployment that the application has, that is, should the application be deployed as a whole, in a unitary way (monolithic), or do we deploy several isolated artifacts independently (distributed)? As a developer, I have always thought that a distributed architecture is a solution that comes after having a monolithic architecture. With the passage of time and the increase of application users, you need to isolate certain parts of your code because they make the rest collapse. I was not wrong, but it is not the only way to get there; moreover, it may be the case that you must start with some distributed architecture for different requirements such as security, elasticity, and legal issues (pe PCI), although it is not usual.

Styles of Software Architecture

Monolithic Architecture

This software architecture style has important benefits, especially when starting an application where the domain is at a very early stage and the boundaries between contexts are very blurred. Something important to keep in mind is that regardless of how long the application has been in production, changes in the domain must be carried out. It’s not something you can leave out; we must update our implementation as often as possible to faithfully represent the domain, and no architecture will save you from this.

The benefit that a monolithic software architecture style can give you is to make change faster. This does not mean that with a distributed architecture, it cannot be done; we are talking about the time it takes and the security when doing it (this implies development cost). At the development level, it also simplifies a lot in the initial stage by only talking about a single repository in a single language.

At the deployment level, it is a bit more complex. At an early stage of the application, simplifying the deployment could help you a lot to focus on the domain. If you introduce microservices at this stage, you are going to have to deal not only with the domain but also with all the infrastructure that goes with it. However, as your application grows, deployments tend to be slower and spaced out over time due to security issues. For example: in e-commerce, wanting to change a small part of the product list implies a deployment not only of that part but of the rest, including the checkout system or other more vital parts, to avoid something that provides benefit being broken by a minuscule change, grouping several small changes in the same one during low-traffic hours.

At the scalability level, I think the same as with the deployment; at an early stage, scale the whole project equally while you collect metrics so that later you can see which part of your project needs to scale more or less (scaling a monolith has its risks but Stack Overflow has already demonstrated that it is very viable). As time goes by, you see that it is not necessary to scale the whole project; it is likely that the product list is something that is visited much more than the checkout or the user profile page, so we could consider some changes when deploying this application (or maybe just adding an elastic, who knows).

Distributed Architecture

When we talk about a distributed architecture, we refer to that type of application where the modules are deployed independently, isolated from the rest, and with communication between them with remote access protocols (e.g., HTTP, grpc, queues, etc.).

They are widely known due to their scalability and availability, among other factors. Performance is usually one of their strong points, especially depending on the granularity of the services. In addition, this type of architecture usually relies heavily on eventual consistency, so events are a widely used means of communication between services. This means that by not waiting for a response from the service to which we send a message, we process the requests we receive faster.

Sending events opens up a wide range of possibilities for communication between services, but we still need transactions between services. This is where one of the weaknesses of distributed architectures comes in: distributed transactions.

The alternative to the distributed transaction is ACID transactions, something impossible to achieve according to the way we dimension our services. In a service-based architecture or microservices where it is more domain-driven (DDD), where services are more coarse-grained, transactions will be ACID (and if they are not, it is very likely that you have a design problem). While in other architectures, for example, EDA, the transactions will be distributed, and there we will need extra pieces (e.g., SAGA, 2PC) to complete, either satisfactorily or not, the transaction. In the event that any part fails, the rest will have to be compensated.

When to Use a Monolithic or a Distributed Architecture

Although it is something that is asked a lot, the answer will always be “it depends," since each project will have different requirements, and depending on these requirements, a decision will be made, but it is not a decision that should be made quickly, it requires certain criteria, experience, and consideration.

It is here where a developer makes the difference, and it is having the ability to see the project from another point of view, a much more global view. Developers will always tend to think more in our day-to-day and not so much in the long term; we will make decisions based on our experience and knowledge, or by mere learning, following the currents of hype. Developers who have the ability to shift their focus to look at the project will make that decision. They will define the characteristics of the application based on the business requirements, whether explicit (they are going to appear in a TV commercial) or implicit (it is an e-commerce, and you know about sales, black Friday, and so on); they will evaluate the different architectures and their tradeoffs and decide which one is more convenient.

That said, as we have already mentioned, monolithic architectures are usually good, among other factors, because of the ease of change, and that is why it is a recommended architecture when you are starting a development. This is not to say that you should not consider the possibility of isolating specific components of your monolith in the future.

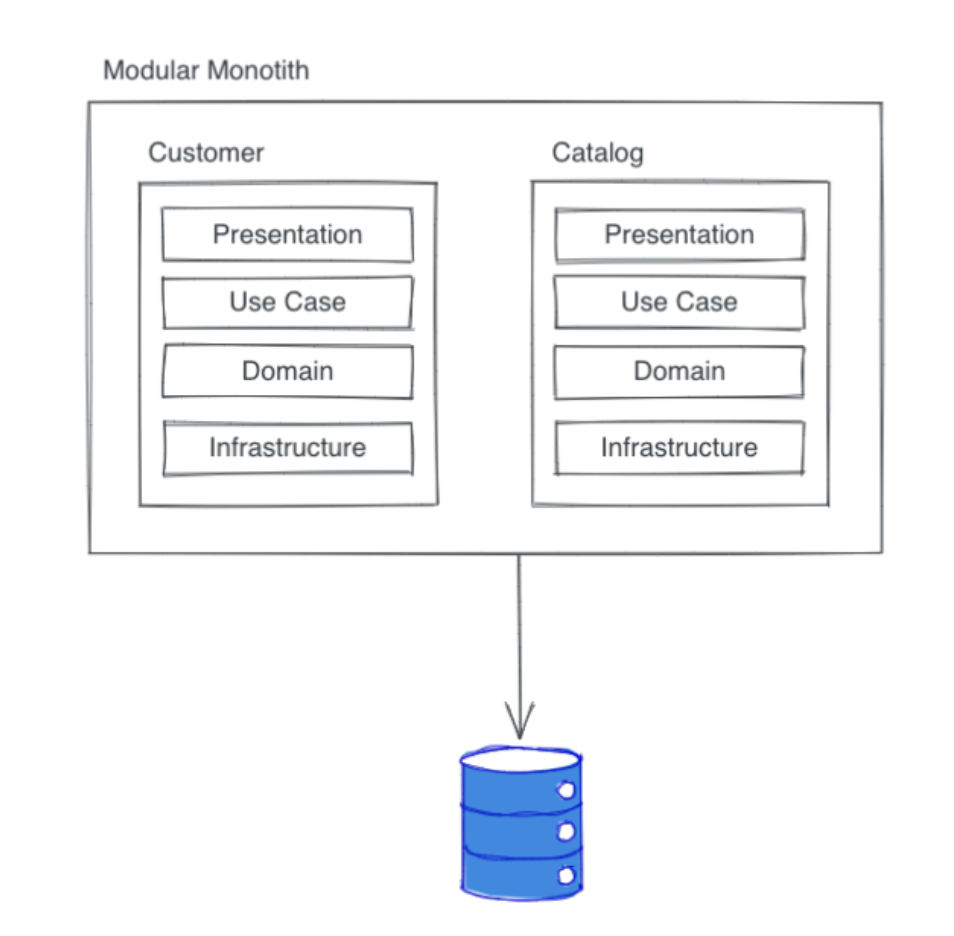

When we usually talk about styles of software architecture, we are referring to top-level styles, that is, the architectures that define the first level. A clear example would be Modular Monolith Architecture, where at the top level, we see a monolithic component divided into modules separated by domain. Still, if we zoom into each domain, we see the layered architecture clearly identified, which would separate the layers by technical components (presentation, domain, or infrastructure, among others).

Monolith or “Big Ball of Mud”?

It is common to come across projects where a “monolith” is harshly criticized. When you dig a little deeper into the project, you realize that the criticism is not directed at the type of architecture but at what is known precisely as the “lack of” architecture, known as the “Big Ball Of Mud.”

This leads to demonizing architecture, something that should not fall into subjectivity. The decision as to whether a monolithic architecture is good or not for the project should be made with weighty arguments, weighing all the trade-offs of both the discarded architecture and the one to be introduced.

The fact that subjectively speaking, monolithic architectures have lost a lot of weight leads to complete project restructurings to move from the big ball of mud to the chosen architecture, microservices, leading us to a new architecture known as the “Distributed Big Ball Of Mud”. Needless to say, there will be teams dedicated exclusively to this, stopping business (or trying to) while such restructuring is being done.

Far from fixing anything, we’ve made our system even more complicated, making it not only difficult to modify, but we’ve added many more points of failure and latency along the way. Oh, and a slightly larger DevOps team.

A much better approach would be to attack the “big ball of mud” in a more direct way while delivering business value by following certain patterns that will help us move to another architecture in a healthier way.

Conclusion

Lack of attention to architecture leads many companies to make decisions that are not the best ones. Even though they will work, they will not work as they should. Mark Richards once said: “There are no wrong answers in architecture, only expensive ones.” And he is absolutely right: when decisions are made based on a single problem and not from a global point of view, the results are not as expected; you solve one problem by adding ten more to the list.

The project will progress, but the delivery to the business will slow down little by little, causing friction between “teams” until reaching a point of no return where the delivery of value to the project will not be affordable, and a possible rewrite will have to be considered, with all that this entails.

Here are some of my conclusions:

- Make decisions as objectively as possible, based on metrics, such as response latency or throughput, if performance is a feature to take into account or the level of coupling based on the instability of our code.

- Read or listen to others’ experiences through books, articles, or a simple conversation with a colleague.

- And for me, the most important thing is to be self-critical and leave the ego aside; most likely, the error is not in how we deploy our code but in a bad design.

Published at DZone with permission of Oscar Galindo. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments