Single-Responsibility Principle Done Right

When adhering to the SOLID programming principles, Single Responsibility can be a bit tricky. Find out why and how to better understand this oft-misunderstood concept.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For Freei am a big fan of the solid programming principles by robert c. martin. in my opinion, uncle bob did a great job when he first defined them in his books. in particular, i thought that the single-responsibility principle was one of the most powerful among these principles, yet one of the most misleading. its definition does not give any rigorous detail on how to apply it. every developer is left to their own experiences and knowledge to define what a responsibility is. well, maybe i found a way to standardize the application of this principle during the development process. let me explain how.

the single-responsibility principle

as is normal for all the big stories, i think it is better to start from the beginning. in 2006, robert c. marting, a.k.a. uncle bob, collected in the book agile principles, patterns, and practices in c# a series of articles that represent the basis of clean programming — the principles are also known as solid. each letter of the word solid refers to a programming principle:

- s stands for single-responsibility principle

- o stands for open-closed principle

- l stands for liskov substitution principle

- i stands for interface segregation principle

- d stands for dependency inversion principle

despite the resonant names and the clearly marketing intent behind them, in the above principles are described some interesting best practices of object-oriented programming.

the single-responsibility principle is one of the most famous of the five. robert uses a very attractive sentence to define it:

a class should have only one reason to change.

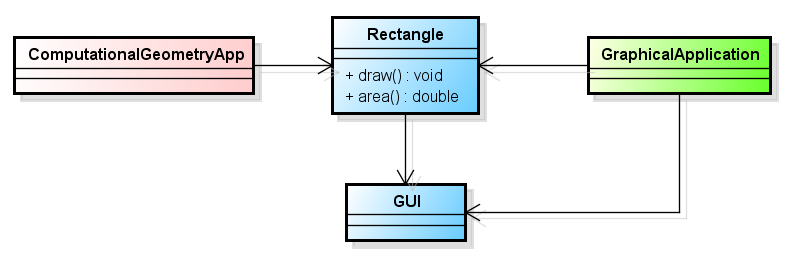

boom. concise, attractive, but so ambiguous. to explain the principle, the author uses an example that is summarized in the following class diagram.

in the above example, the class

rectangle

is said to have at least

two responsibilities

: drawing a rectangle on a gui and calculating the area of that rectangle. is that really bad? well, yes. for example, this design forces the

computationalgeometryapp

class to have a dependency on the class

gui

.

moreover, having more than one responsibility means that every time a change to a requirement linked to the user interface comes, there is a non-zero probability that the class

computationalgeometryapp

could be changed, too. this is also the link between

responsibilities

and

reasons to change

.

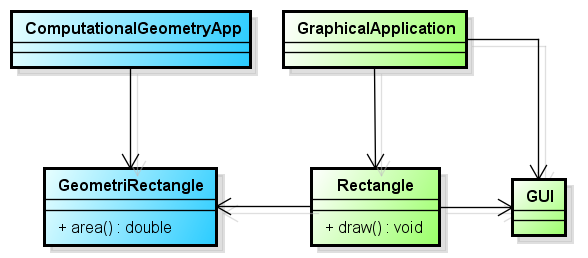

the design that completely adheres to the single-responsibility principle is the following.

arranging the dependencies among classes as depicted in the above class diagram, the geometrical application does not depend on user interface stuff anymore.

the dark side of the single-responsibility principle

well, this is probably a problem with me, but i never thought that a principle should be defined in such a way that two different people can understand it the same way. there should be no space left for interpretation. a principle should be defined using a quantitative approach , rather than a qualitative approach . again, probably my fault — it comes from my mathematical extraction.

but given the above definition of the single-responsibility principle, it is clear that there is no mathematical rigor to it.

every developer, using their own experience can give a different meaning to the word responsibility . the most common misunderstanding regarding responsibilities is finding the right grain to achieve.

recently, a “famous” blogger in the field of programming, yegor bugayenko, published a post on his blog in which he discusses how the single-responsibility principle is a hoax: srp is a hoax . in the post, he gave an incorrect interpretation of the conception of responsibility, in my opinion.

he started from a simple type that aims to manage objects stored in aws s3.

class awsocket {

boolean exists() { /* ... */ }

void read(final outputstream output) { /* ... */ }

void write(final inputstream input) { /* ... */ }

}

in his opinion, the above class has more than one responsibility:

- checking the existence of an object in aws s3

- reading its content

- modifying its content

hmm.

so, he proposes to split the class into three different new types,

existencechecker

,

contentreader

, and

contentwriter

. with this new type, in order to read the content and print it to the console, the following code is needed.

if (new existencechecker(ocket.aws()).exists()) {

new contentreader(ocket.aws()).read(system.out);

}

as you can see, yegor's experience drives him to define too finely grained responsibilities, leading to three types that clearly are not properly cohesive .

where is the problem with yegor's interpretation? what is the keystone to comprehending the single-responsibility principle? cohesion .

it’s all about cohesion

uncle bob opens the chapter dedicated to the single-responsibility principle with the following two sentences.

this principle was described in the work of tom demarco and meilir page-jones. they called it cohesion. they defined cohesion as the functional relatedness of the elements of a module.

wikipedia defines cohesion as:

the degree to which the elements inside a module belong together. in one sense, it is a measure of the strength of relationship between the methods and data of a class and some unifying purpose or concept served by that class.

so, what is the relationship between the single-responsibility principle and cohesion? cohesion gives us a formal rule to apply when we are in doubt if a type owns more than one responsibility. if a client of a type tends to always use all the functions of that type, then the type is probably highly cohesive. this means that it owns only one responsibility, and hence has only one reason for changing.

it turns out that, like the open-closed principle, you cannot say whether a class fulfills the single-responsibility principle in isolation. you need to look at its incoming dependencies . in other words, the clients of a class define whether it fulfills the principle .

shocking.

looking back at yegor's example, it is clear that the three classes he created, thinking of adhering to the single-responsibility principle in this way, are loosely cohesive and hence tightly coupled. the classes

existencechecker

,

contentreader

, and

contentwriter

will probably always be used together.

pushing to the limit: effects on the degree of dependency

in the post dependency , i defined a mathematical framework to derive a degree of dependency between types. the natural question that arises is that, upon applying the above reasoning, does the degree of dependency of the overall architecture decrease or increase?

well, first of all, let’s recall how we can obtain the total degree of dependency of a type

a

.

in our case, type

a

is the client of the class

awsocket

. recalling that the value of

δ

a

→

c

j

ranges between 0 and 1, dividing without any motivation the class

awsocket

into three different types will not increase the overall degree of dependency of client

a

. in fact, the normalizing factor

1

n

assure us that refactoring processes will not increase the local degree of dependency.

the overall degree of the entire architecture will instead increase since we have three new types that still depend on

awsocket

.

does this mean that the view of the single-responsibility principle i gave during the post is wrong? no, it does not. however, it shows us that the mathematical framework is incomplete. probably, the formula for the degree of dependency should be recursive, in order to take into consideration the addition of new tightly coupled types.

conclusions

starting from the definition given by robert c. martin of the single-responsibility principle, we showed how simple is to misunderstand it. in order to give some more formal definition, we showed how the principle can be viewed in terms of the concept of cohesion. finally, we try to give a mathematical proof of what we have done, but we went onto the conclusion that the framework that we were using is incomplete.

happy new year!

references

Published at DZone with permission of Riccardo Cardin, DZone MVB. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments