Saga Pattern | How to Implement Business Transactions Using Microservices - Part I

In this article, you'll learn about the Saga Pattern for distributed transactions and how it can help businesses working with microservices.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeOne of the most powerful types of transactions is called a Two-Phase Commit, which is in summary when the commit of a first transaction depends on the completion of a second. It is useful especially when you have to update multiple entities at the same time, like confirming an order and updating the stock at once.

However, when you are working with microservices, for example, things get more complicated. Each service is a system apart with its own database, and you no longer can leverage the simplicity of local two-phase-commits to maintain the consistency of your whole system.

When you lose this ability, RDBMS becomes quite a bad choice for storage, as you could accomplish the same "single entity atomic transaction" but dozens of times faster by just using a NoSQL database like Couchbase. That is why the majority of companies working with microservices are also using NoSQL.

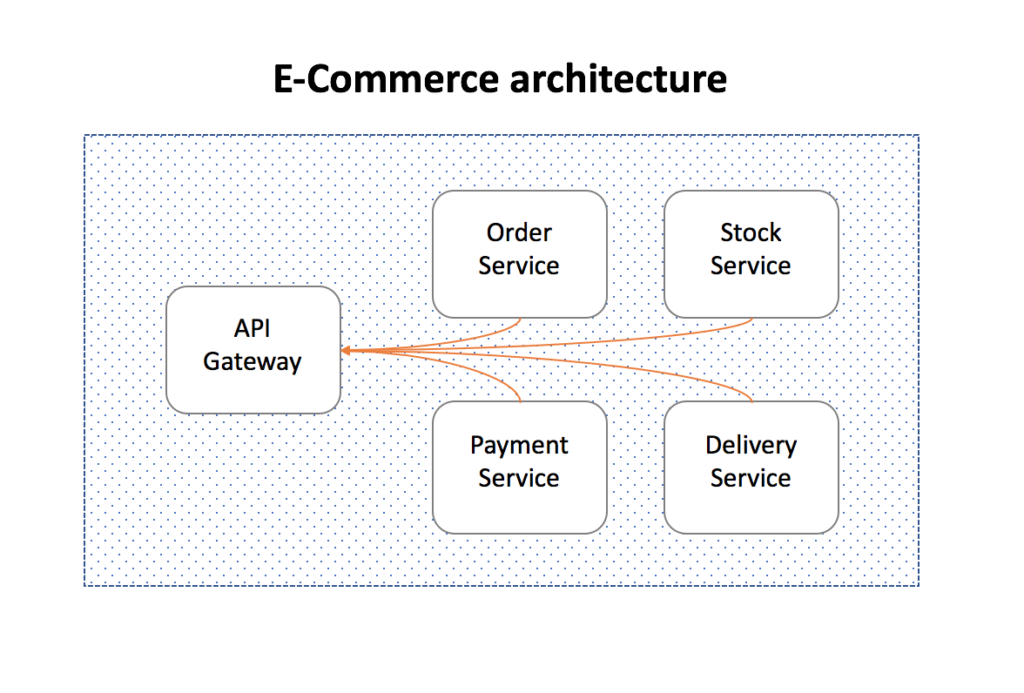

To exemplify this problem, consider the following high-level microservices architecture of an e-commerce system:

In the example above, one can't just place an order, charge the customer, update the stock, and send it to delivery all in a single ACID transaction. To execute this entire flow consistently, you would be required to create a distributed transaction.

We all know how difficult it is to implement anything distributed, and transactions, unfortunately, are no exception. Dealing with transient states, eventual consistency between services, isolations, and rollbacks are scenarios that should be considered during the design phase.

Fortunately, we have already come up with some good patterns for it, as we have been implementing distributed transactions for over twenty years now. The one that I would like to talk about today is called the Saga pattern.

The Saga Pattern

One of the most well-known patterns for distributed transactions is called Saga. The first paper about it was published back in 1987, and it has been a popular solution since then.

A Saga is a sequence of local transactions where each transaction updates data within a single service. The first transaction is initiated by an external request corresponding to the system operation, and then each subsequent step is triggered by the completion of the previous one.

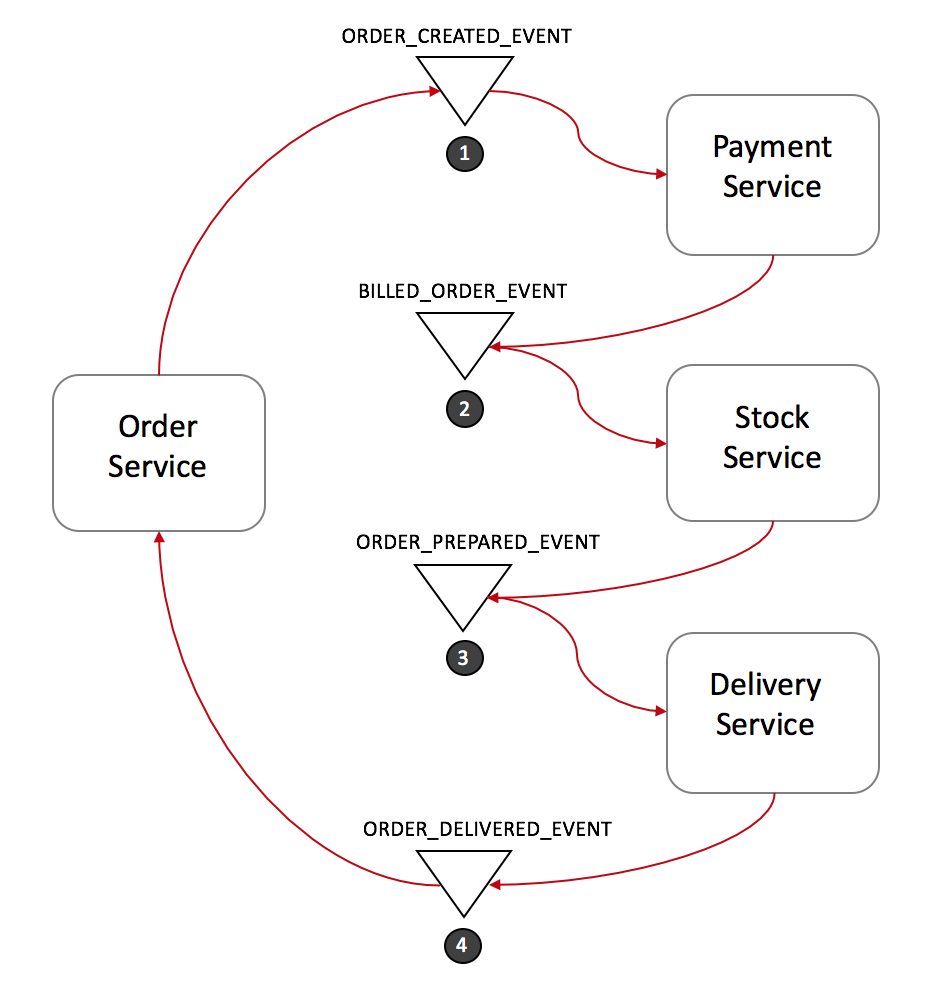

Using our previous e-commerce example, in a very high-level design, a Saga implementation would look like the following:

There are a couple of different ways to implement a saga transaction, but the two most popular are:

- Events/Choreography: When there is no central coordination, each service produces and listens to the other service's events and decides if an action should be taken or not.

- Command/Orchestration: When a coordinator service is responsible for centralizing the saga's decision making and sequencing business logic.

Let's go a little bit deeper into each implementation to understand how they work.

Events/Choreography

In the Events/Choreography approach, the first service executes a transaction and then publishes an event. This event is listened to by one or more services, which execute local transactions and publish (or don't publish) new events.

The distributed transaction ends when the last service executes its local transaction and does not publish any events, or the event published is not heard by any of the saga's participants.

Let's see how it would look in our e-commerce example:

- Order Service saves a new order, set the state as pending and publish an event called ORDER_CREATED_EVENT.

- The Payment Service listens to ORDER_CREATED_EVENT, charge the client and publish the event BILLED_ORDER_EVENT.

- The Stock Service listens to BILLED_ORDER_EVENT, update the stock, prepare the products bought in the order and publish ORDER_PREPARED_EVENT.

- Delivery Service listens to ORDER_PREPARED_EVENT and then pick up and deliver the product. At the end, it publishes an ORDER_DELIVERED_EVENT

- Finally, Order Service listens to ORDER_DELIVERED_EVENT and set the state of the order as concluded.

In the case above, if the state of the order needs to be tracked, Order Service could simply listen to all events and update its state.

Rollbacks in distributed transactions

Rolling back a distributed transaction does not come for free. Normally you have to implement another operation/transaction to compensate for what has been done before.

Suppose that Stock Service has failed during a transaction. Let's see what the rollback would look like:

- Stock Service produces PRODUCT_OUT_OF_STOCK_EVENT;

- Both Order Service and Payment Service listen to the previous message:

- Payment Service refund the client.

- Order Service set the order state as failed.

Note that it is crucial to define a common shared ID for each transaction, so whenever you throw an event, all listeners can know right away which transaction it refers to.

Benefits and Drawbacks of Saga's Event/Choreography Design

Events/Choreography is a natural way to implement Saga's pattern; it is simple, easy to understand, does not require much effort to build, and all participants are loosely coupled as they don't have direct knowledge of each other. If your transaction involves 2 to 4 steps, it might be a very good fit.

However, this approach can rapidly become confusing if you keep adding extra steps in your transaction, as it is difficult to track which services listen to which events. Moreover, it also might add a cyclic dependency between services, as they have to subscribe to one another's events.

Finally, testing would be tricky to implement using this design. In order to simulate the transaction behavior, you should have all services running.

In the next post, I will explain how to address most of the problems with Saga's Events/Choreography approach using another Saga implementation called Command/Orchestration.

In the meantime, if you have any questions, feel free to ask me at @deniswsrosa.

Published at DZone with permission of Denis W S Rosa, DZone MVB. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments