Reverse Pull Requests

This article explains how we used GitHub PRs in a trunk-based, continuous deployment development team.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeIn a fast-paced world, more teams have microservices architectures and are making the shift to Continuous Deployment and Trunk-Based Development. For one of our client’s teams, that meant no feature branches, pairs always committing to main, pushing frequently (multiple times per hour, as often as every 1–4 commits) and those changes landing in production 20–30 minutes later.

With pair programming, no feature branches, and such continuous change, code reviews would seem redundant or extremely difficult with little in the way of tooling support. How on earth would you use GitHub’s Pull Request review features in this setting when there’s no feature branch to diff?

We found that not only were code reviews valuable, GitHub’s Pull Request review features played a key part in the process using an approach we called ‘Reverse Pull Requests.’

The Context

The product was a set of APIs used by other apps in the business, most significantly their e-commerce platform, supporting millions of dollars in revenue each month. The team was made up of developers with a wide range of experience. Antony had been a Player-Coach on the team, setting direction on architecture and coaching the team since its inception. Lukasz was brought in to help realize Antony’s envisioned event-driven element of our microservices architecture on the client’s specific tech stack.

The team had made a conscious decision to maximize flexibility by having a single Git repository per microservice, working around the challenges with repository automation. Each microservice was 10s lines of code, excluding any boilerplate, configuration, and test code. The team applied pair/mob programming on a daily basis.

The number of source code repositories had already outgrown the number of pairs, or even the number of developers, in the team. This meant that there was very little chance of any pairs working on the same repository at any one time.

To apply continuous delivery, it was necessary to achieve high code coverage with high-quality tests across the entire testing spectrum (e.g., unit, component, CDC, end-to-end).

Something Was Missing

It all was working very smoothly, delivering business value faster than any other team in the company with a level of agility so high that the team was able to change the course of development on request almost immediately.

However, what was missing was wider visibility of changes being applied to the code. Due to the number of microservices (around 40) and the fact that new functionality was generally achieved by creating a new microservice, some developers didn’t get to see many of the codebases for some time. This resulted in projects becoming inconsistent in terms of design patterns, code conventions, and even code quality.

The question was, how could we improve the code quality and its consistency? How could we improve knowledge sharing by increasing exposure of solutions used elsewhere in the code to more team members?

Could Code-Reviews Be The Answer?

We already had a daily forum called ‘Tech Chat’ for discussing design, technical challenges, or sharing novel solutions. However, this lacked the serendipitous learning that can arise from routinely reviewing code.

Most of the more experienced team members were familiar with code reviews — especially using GitHub Pull Requests, and this seemed like the perfect solution to our problem. Except, a GitHub pull request assumes you have a feature branch that you’re merging into the main branch. This is something we clearly didn’t have!

Some may argue that there’s no need for code review when pairing. We always believe in testing out ideas, so we decided to give it a try and see what we learned. We tried it on one of the user stories being worked on to see what we could learn.

However, the challenge was how to ship code to production and do code reviews continuously. Well, we know we can’t work off of a feature branch since that would destroy the pace we were able to work at. So, we needed another solution!

Reverse Pull Requests

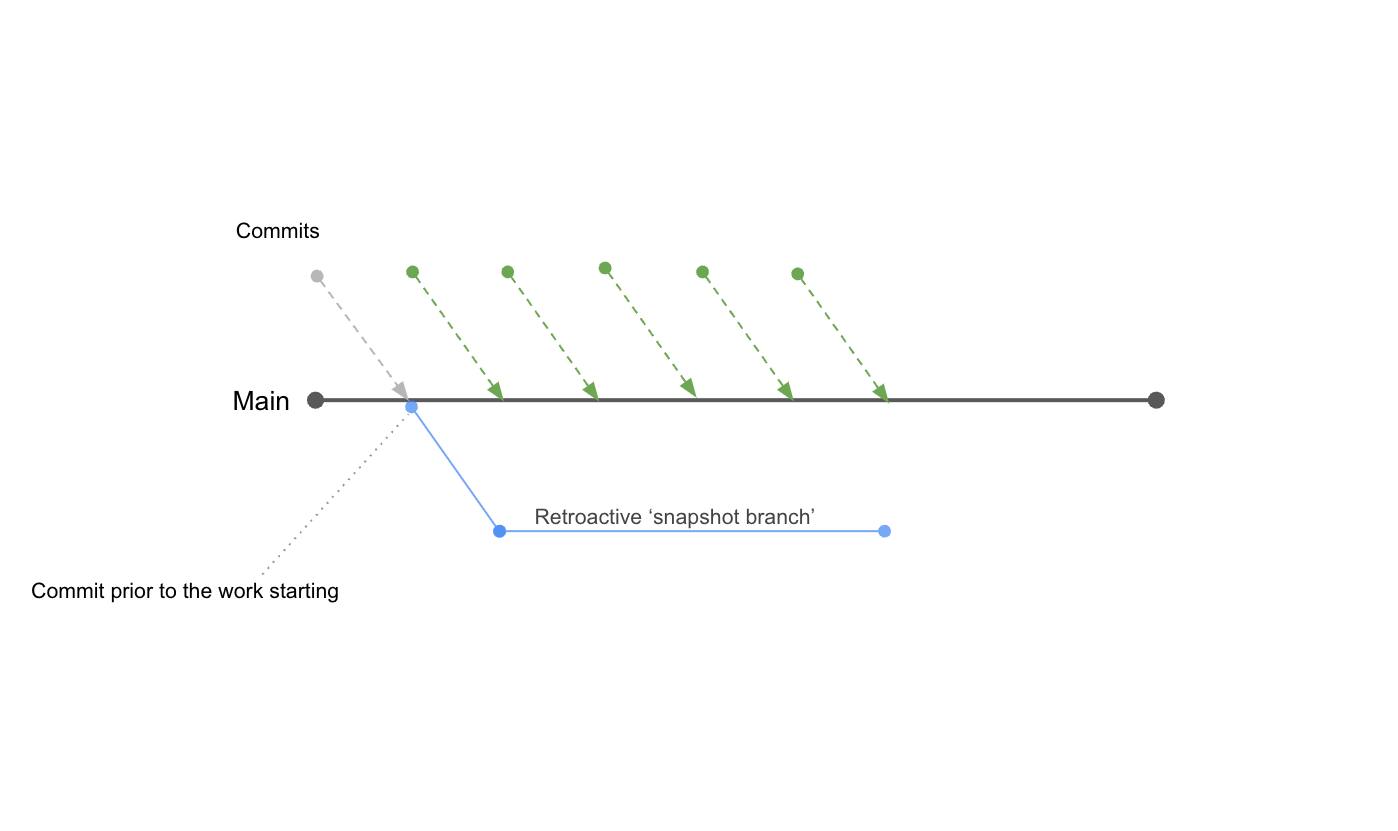

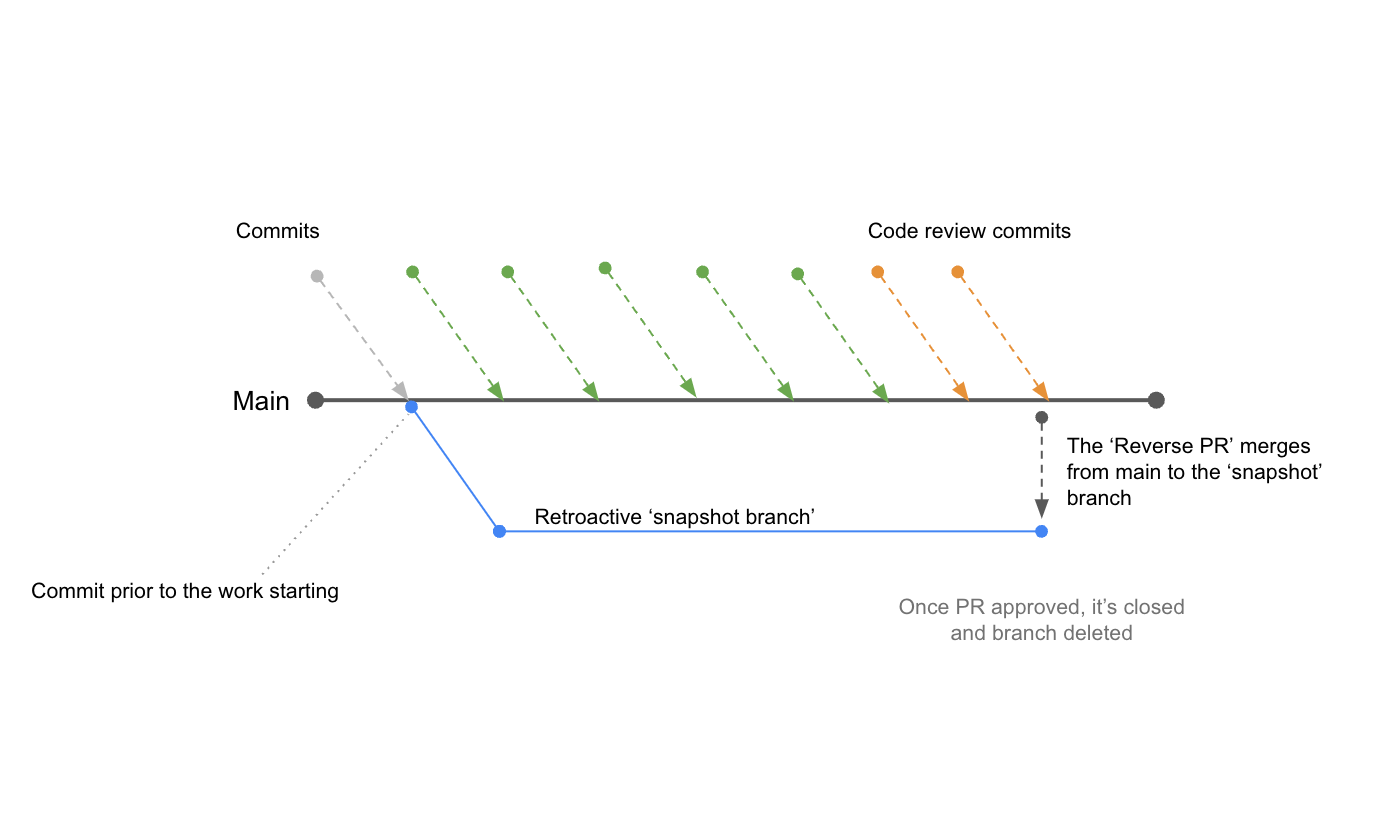

If, by design, we don’t work on branches – what we can do instead? This was the question Antony asked. Lukasz had the answer: Instead of a branch that merges to main/master, we can create a branch from just before the work was started. The pull request merges from master/main into the newly created branch. This gives us the same difference as in a traditional pull request and the tooling to capture our thoughts and feedback on the chosen solution. We named this a Reverse Pull Request.

Here’s how this works.

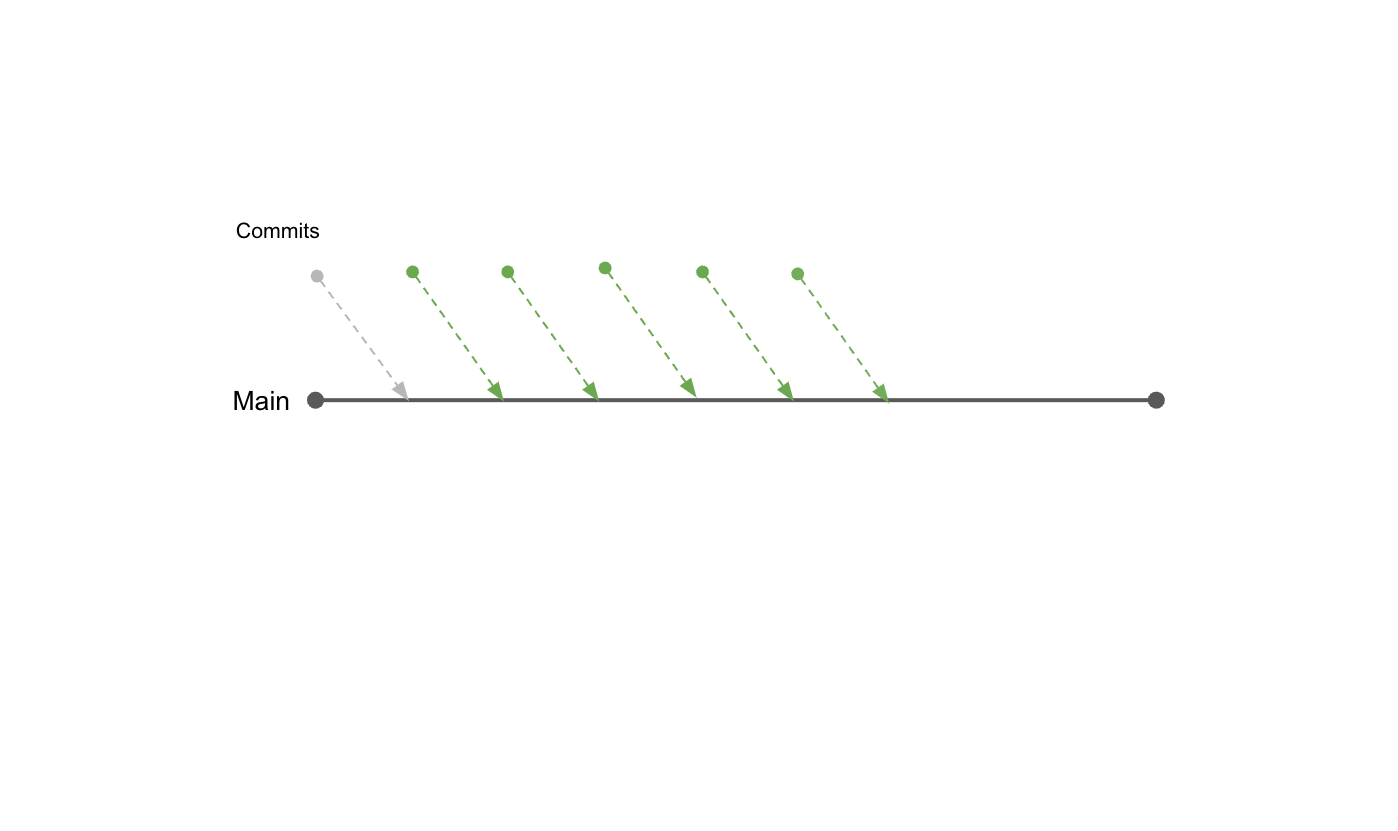

A pair, a mob, or a single developer continuously commits to master/main and pushes the commits so that the changes can make their way through a pipeline to production. Once the story is functionally complete, and the pair are happy with the code, that piece of work is ready to be reviewed.

A branch is then created from the commit right before the work starts. This is essentially a snapshot of master/main just before the work starts.

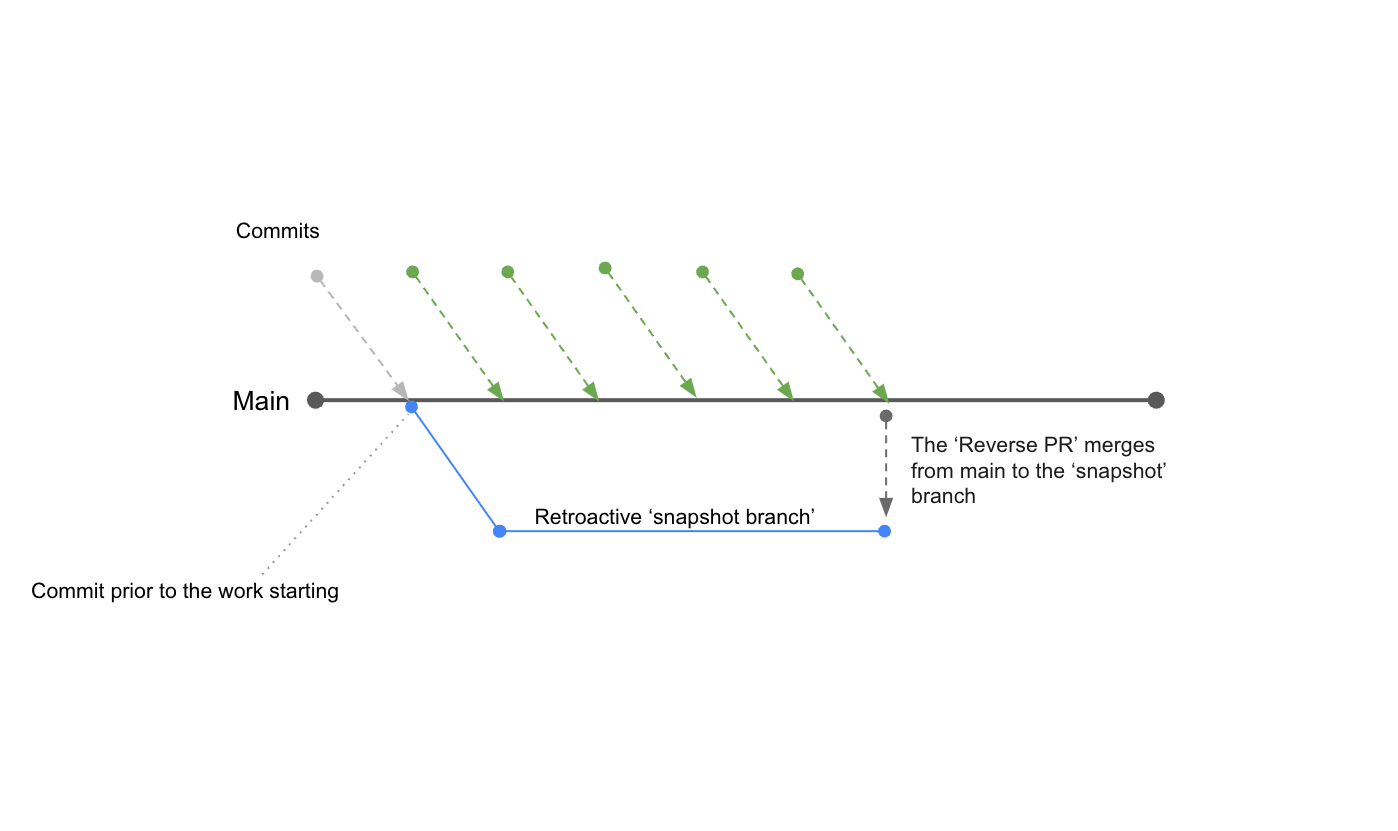

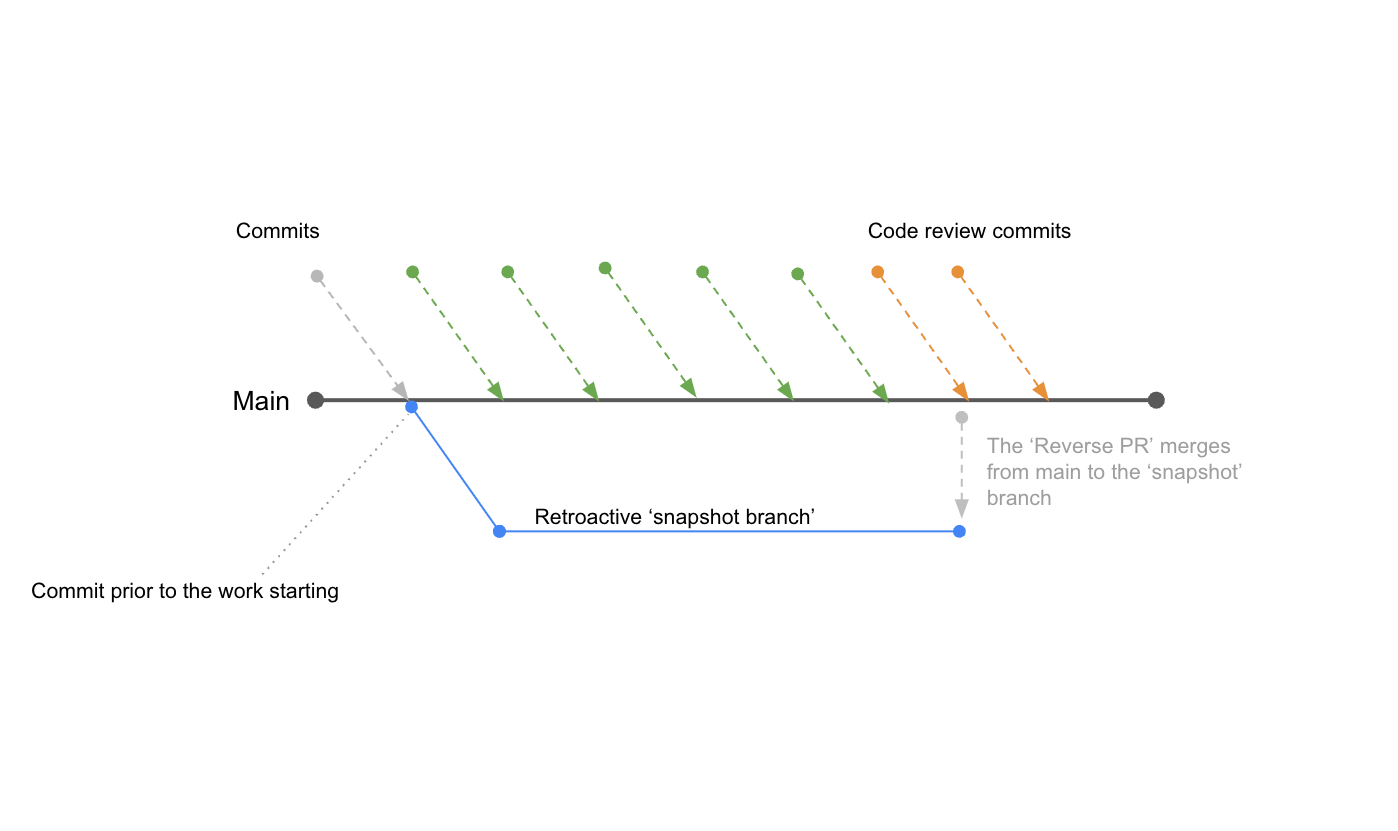

When that branch is pushed, a pull request is raised for merging the master branch to that new branch (rather than the other way round, as would normally be the case).

Then all the usual PR-related activities take place, e.g., commenting, discussions, code changes, etc.

One practice that was explored but never took hold was to create the snapshot branch when starting the work so that it was there and ready for the PR. This may be something you could try.

The Reverse Pull Request is essentially an alternative way to allow you to leverage GitHub’s code-review features while retaining the flow achieved by committing and pushing only to the main/master. However, there may be some circumstances where this may not work for you.

Limitations

As much as we find reverse PRs useful, we understand that they are not practical or applicable to many teams, especially those working with a mono-repo or when the developer-repository ratio is high enough that working on the same codebase is so frequent that it’s hard to separate the changes made by one pair from another.

Therefore, it’s reasonable to ask, what if multiple changes are being worked on in the same repo simultaneously? How are the combined changes reviewed? What if non-story commits are made partway through the story, such as cross-cutting refactoring or library updates? The intermingling of too many unrelated changes can make the diff incoherent.

These are all good questions. We didn’t have to deal with those scenarios too often due to the ways of working described above. It’s actually not much of a problem if an unrelated change or two make it into a PR. The person raising the PR can always refer to the author of the change in the PR comments. Yet, there are possible ways of handling the scenarios above (albeit not yet tried by us).

To avoid later changes confusing the diff, you can use a PR that merges two non-master branches. Imagine creating a new branch from a commit right before the relevant changes (as described above) and another branch from the last relevant commit. Then a PR can be raised to merge the latter branch into the former achieving the required diff.

This approach may cater to the scenario from a reviewing perspective but would not keep any subsequent improvements from the feedback. This could be captured in a new PR. We’d love to hear your ideas on how you would handle this case.

Cherry picking is another potential solution to limiting the PR to relevant changes only. We will leave this for the reader to explore the feasibility of this approach in their environment. Another method may be to filter out commits in the IDE, as is possible in IntelliJ IDEA.

Conclusions

Firstly, after trying this approach, we found that code reviews were helpful, even when working in pairs! Yes! Pair Programming fulfilled much of what you’d get from code reviews but not always, and not all the benefits.

We found that there’s something different about a code review. It’s like there’s a different perspective, with less bias than when pairing. You have a fresh pair of eyes since you’re unlikely to have worked on the change. Or, you bring a fresher pair of eyes if you were among the first team members who paired on it, and it’s been a couple of days since you rotated off that story. Or, you spot that things went a little off track.

It also gives team members serendipitous opportunities to learn from each other, to see how a problem was solved, the spot that there’s a similar problem to the one they’re solving, and consolidate a shared solution into a library or apply a similar pattern or language feature they didn’t know of before.

For us, reverse pull requests boosted code quality, knowledge transfer, and consistency. It raised topics for our daily tech chats that resulted in new conventions being agreed upon and improved overall design in a way that was non-blocking.

The code was shipped continuously, so the value was being realized — it was more a question of ensuring the code was left in a state that was easy to understand and change in the future.

For these reasons, after experimenting with the Reverse PR approach, the team decided to retain the practice. It’s become an integral part of the way the team works, and having two approvals on the Reverse PR is the last item on this team’s definition of done.

While the solution described here may seem to have limited applicability, in the right environment, it may help you achieve similar results. Treat it like an experiment, as with any change, if you think this may work for you. Apply it on a small scale, to begin with, and see what you learn.

Published at DZone with permission of Lukasz Gryzbon. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments