Starting Communities of Practice in Your Organization

Everything you need to know about the concept of Community of Practices and how to engage collaborations in multiple Agile teams across the organization.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeGraphics made by Max Degtyarev

What Is a Community of Practice?

A community of practice (CoP) is a group of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly. Unlike a regular team, which is held together by a shared task, a community of practice is held together by the “learning value” members find in their interactions, and usually contains members of multiple existing teams.

As an example, Automation Quality Assurance engineers spread across multiple scrum teams should define their community of practice to regularly interact with each other with a goal of maintaining and improving automation best practices across teams in your organization. As counter-examples, a scrum team itself, the whole Agile Release Train, or the whole department are not communities of practice.

There are three key pillars of a community of practice:

The domain is the shared domain of interest. It is a concern, a set of problems, or a passion for a topic. Members of communities of practice are all committed to their designated domain to improve their craft, collaborate with other employees, and strategize in solving relevant hurdles within a company.

Community is where members interact and learn from each other about how they can improve their work and tackle discoveries in their chosen domains. Members engage in joint activities and discussions, help each other, and share information.

Practice is where the members share knowledge, discover methods, learn cases, and exchange tools that can help the members solve common problems. This is a shared repertoire of resources: experience, stories, tools, ways of addressing recurring problems, etc.

Communities of practice can be organized around any one of three aspects of work:

- Role

- Business problem

- Process

Why Use Communities of Practice?

Communities of practice (CoPs) connect people with common goals and interests for the purpose of sharing resources, strategies, innovations, and support. CoPs support the transmission and expansion of knowledge and expertise for leaders, learners, and professionals in any field or discipline. CoPs contribute to a more connected and collaborative global community in your field of expertise.

Members of the community can brainstorm new tools and processes, and try or explore new ways of communication/organization/development that still incorporates the company’s objectives. Communities of practice are not only limited to solving problems and meeting the company’s objectives. CoPs can also help you:

- Reuse assets that can lower expenses,

- Discuss and disseminate developments in the field, and

- Identify and resolve gaps within the company.

Three characteristics or qualities define a practice:

- Joint Enterprise: The members of a CoP are there to accomplish something on an ongoing basis. They have some kind of work in common and they clearly see the larger purpose of that work. They have a mission.

- Mutual Engagement: The members of a CoP interact with one another not just in the course of doing their work but to clarify that work, to define how it is done, and even to change how it is done.

- Shared Repertoire: The members of a CoP not only have work in common, but also methods, tools, techniques, and even language, stories, and behavior patterns unique to their domain.

Two indicators stand out from all the rest:

- People have a strong sense of identity tied to the community (e.g., as technicians, salespeople, researchers, and so on).

- The practice itself is not fully captured in formal procedures. People learn how to do what they do and come to be seen as competent (or not) by doing it in concert with others.

Thus, the main responsibility of communities of practice is to build a community of highly engaged and collaborative colleagues to effectively grow, train, and coach each other in the domain or field, find ways to solve identical problems, and unify approaches, tools, and methods used across the organization.

Key concepts for successful implementation of CoPs

The Facilitator’s Role Is Essential

Our practical experience shows that most thriving CoPs have several attributes in common:

- Someone becomes a Facilitator and dedicates some time to organizing meetings and notes, engaging in conversations, driving learning and brainstorming activities, and keeping up communication inside and outside the group.

- Each community of practice decides whether they are private or public, allowing anyone to join as a listener or contributor at any time. Still, all CoPs maintain transparent and regular external communication with executive leadership (CTO, VP, CEO, etc.) and/or engineering management (Engineering Managers, Scrum Masters, Architects) about the results (even partial) of the work they have done, lessons they learned, problems they have solved. This communication might be informal (chat, email, a voice call, etc.), and it’s up to members to decide who is responsible for it. But if no one is assigned, it’s the Facilitator’s responsibility.

- When only one person takes on the Facilitator role, it usually takes up to 20% of that person’s time to fulfill all the needs of the CoP.

The Facilitator’s role is essential for CoPs to be productive, as it helps to maintain a healthy communication, synchronize across teams, drive engagement and motivation, and ultimately helps get important things done. It is also beneficial for the person acting as a Facilitator. The work can help grow or pivot your career by gaining leadership experience, improving soft skills, and learning more about the company, teams, people, tools, and other accompanying staff.

Facilitating Patterns To Use

- You should provide the infrastructure needed by the community to meet their objectives and be productive. This infrastructure may be information, supplies, or allotted time for discussion/interaction and so forth. A web page with links to relevant resources might be useful, but the real action in a CoP is in the interactions among members. Start small and evolve.

- Keeping things simple and informal, since all members of a community of practice have their professional obligations to the company, and providing them minimal responsibilities is highly recommended. Do not force them to overwork; let their creativity and ideas flow naturally. Give them the privilege of expressing their thoughts.

Requiring CoP members to attend several meetings in just one day makes them feel exhausted and unproductive. Levying demands and imposing strong expectations can quickly convert a CoP into a project team focused on tasks and deliverables. The team will drive toward satisfying the boss — instead of producing and sharing new knowledge. - The success of a CoP hinges on trust between and among its members.

- Do stay focused on the primary purposes of a CoP: to learn from each other through sharing and collaborating.

- Appreciating and identifying the efforts of the members of the communities of practice will motivate them. Remember the reason you gathered them into a CoP in the first place. A simple gift certificate from a related event in their domain or allowing them to have at least one free day to discuss and execute their ideas makes them feel more valued in the company.

Best Practices for Organizing Communities of Practice

Use a “light hand”. Mandates to “launch” CoPs may create resistance to what could be viewed as the next corporate program to wait out.

- Send a continuing message reinforcing the business value of CoPs.

- Provide information to others about what CoPs are, how they operate, how to support and encourage them — and how to avoid undercutting them.

- Encourage appropriate professionals to form CoPs that focus on key business issues at the unit, sector, process, function, or company level.

- Seek out and subtly promote a few exemplar CoPs. Point to solid results and value added — but don’t overdo it.

- Spend time with a few existing CoPs to learn first-hand how they operate.

- Leverage outside events (e.g., bring attendees together afterward and de-brief the sessions attended).

Work Items

It’s not a surprise that members of a CoP may generate some amount of work to do. But members of a CoP usually have their daily jobs in the Scrum teams. And it might be hard to prioritize one another. It’s helpful to go through the following steps to execute an additional amount of work desired by members of a CoP:

- Decide whether some members should do this work as part of their main daily job in the Scrum team, or as an additional activity outside the group.

- All the work finished as part of the team’s backlogs should be demoed in the usual cadence (i.e., at the end of iteration) and should not be treated as something different. It should also be welcoming to demo anything CoP did as an additional activity inside a CoP.

Work Inside vs Outside the CoP

The rule of thumb is to decide based on work estimate: if this work item is Epic-sized, then it is a candidate for the Scrum team backlog. Otherwise (Story-sized), it can be an additional activity.

Usually, Epic-sized work items should be transparently discussed with Scrum team members (including QA, PO, SM, and devs). A member of CoP should convince the team to take the item into a team backlog, plan, execute and deliver this work.

Story-sized work items can be completed relatively quickly and should not require the allocation of many resources or affect any Scrum team commitments. Thus, this work might be considered lightweight.

The Ways to Demo the Work Done by the CoP

How to demo results of CoP’s work:

- Present results during a regular demo ceremony

- Write and publish brief articles or results descriptions in company or unit communication vehicles

- Create special communications: your CoP might periodically produce and distribute its own newsletter or blog

- Invite others to special briefings where your CoP members share their learning and results

- Publish articles in external journals or magazines and then distribute them internally (after clearing through proper company channels)

Why Exert the Effort to Market Your Cop’s Results?

Several reasons:

- To generate enthusiasm among current members

- To ensure continued resources and support from your sponsor(s)

- To stimulate interest in joining from high-potential prospective members

- To promote interest on the part of your colleagues in finding out what the members of your CoP have learned and, as a result, to share what they have learned with your CoP

- To better leverage the knowledge created and the learnings generated by your CoP

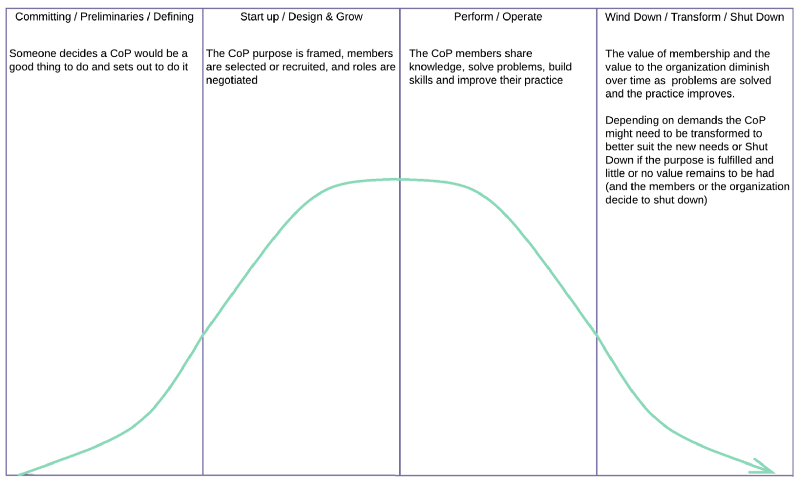

Lifecycle

Last but not least, to understand is that like any other group of people, a community of practice has phases or lifecycle stages. First, we define a new CoP. Then we have to find the best way to collaborate (including communication, learning, and working together) and run it. Later, at some point, the group may feel the need to transform to another kind of CoP or to shut down forever. Those phases are meant to be flexible, so any phase can be skipped or repeated based on your community of practice’s needs.

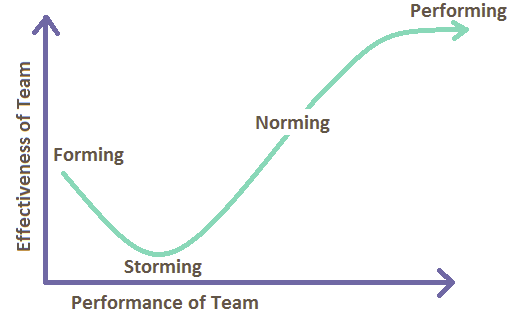

Usually, groups of people need some time to pass each stage, whether fast or slow. It’s not expected that every community of practice will immediately move quickly. The four-stage Bruce Tuckman model of team development — Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing — can be applied to CoPs. It’s normal that things change going forward and a shutdown decision may be made by the CoP members themselves. It might be helpful to consider transforming instead of shutting down, to ensure that your CoP is adaptive to changes in funding or goals.

Checklists

I want to start a new community of practice. What should I do?

Start by creating a Community of Practice wiki-like page in the organization's web portal. The page should cover the following attributes:

- The facilitator is identified (i.e. who drives creation, leads this CoP, facilitates necessary changes)

- The sponsor is identified (i.e. who can approve the creation of this CoP based on the proposal)

- An aspect of work selected (a role, business problem, or process to focus on)

- Roles identified

- Value/benefits

- Sponsorship/support (where resources or support will be needed)

- Interactions

- Outcomes

- List members

The proposal presented to the sponsor and approvals are received

- First meetings scheduled:

- Initial agreements with members received

- The agenda is set for the initial interaction

- Issues/interests listed

- Problems listed

- Goals/outcomes listed

- Interaction modes selected and agreed

- Email distribution groups

- 1-1 meetings

- Scheduled/unscheduled

- Conference calls/group meetings

- Videoconferencing

Run the following recurring practices/events using the Best Practices covered above:

- Meetings

- Processes

- Interactions

Success is measured periodically and adjusted,

How Can I Measure the Success of My Community of Practice?

CoPs don’t just happen; it takes hard work to form and sustain them. Regardless of your role—Sponsor, Champion, Facilitator, Practice Leader, Information Integrator, or Member—all members of your CoP should take some responsibility for marketing and promoting their CoP. Each member individually, and your CoP collectively, will want to market the value of your CoP. This means generating interest in your CoP and demonstrating its value. Both members and non-members need to know the value of their CoP: what real benefits accrue to the members and the company from the investment of time, energy, and resources in the CoP?

Check if your CoP is successful with this checklist of indicators below. Complete alignment with the checklist is not expected, but the more boxes you check, the closer to ideal your CoP is:

Members of the CoP share a fairly broad consensus about who is "in" and who is "out"

- A shared, evolving language (e.g., special terms, jargon, "shortcuts" such as acronyms, etc.)

- Perspectives reflected in the language that suggest a common way of viewing the world (e.g., shared analogies, examples, explanations, etc.)

- Shared ways of doing things together (i.e., common practices and beliefs about best practices)

- A widespread and shared awareness of each others’ competencies, strengths, shortcomings and contributions

- Members of the CoP share experiences and know-how

- Continuing mutual relationships—regular, work-related interactions

- Common tools, methods, techniques, and artifacts such as forms, job aids, etc.

- Capture/codify new know-how

- Members of the CoP experiment with new ideas and novel approaches

- A rapid flow of information between and among members

- Quick diffusion of innovation among members (e.g., rapid transfer of best practices)

- Members of the CoP discuss common issues and interests, collaborate in solving problems

- Conversations come quickly to the point (i.e., no lengthy lead-ins)

- Problems are quickly framed (i.e., a common understanding of the milieu in which they all operate)

- Group analyze causes and contributing factors

- Members of the CoP evaluate actions and effects

- Learning

- Resolving issues

- Solving business problems

Where To Learn More

- https://www.scaledagileframework.com/communities-of-practice/

- https://teachingcommons.lakeheadu.ca/communities-practice-quick-start-guide

- https://www.organisationalmastery.com/communities-of-practice/

- https://www.nickols.us/CoPStartUpKit.pdf

- https://ktdrr.org/resources/rush/copmanual/CoP_Manual.pdf

- https://www.talent.wisc.edu/home/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=B6rgxakCMtI%3D&portalid=0

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments