Patterns for Microservices — Sync vs. Async

Learn about the different types of microservices patterns, synchronous and asynchronous, and the strengths and trade-offs of each.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeMicroservices is an architecture paradigm. In this architectural style, small and independent components work together as a system. Despite its higher operational complexity, the paradigm has seen a rapid adoption. It is because it helps break down a complex system into manageable services. The services embrace micro-level concerns like single responsibility, separation of concerns, modularity, etc.

Patterns for Microservices is a series of blogs. Each blog will focus on an architectural pattern of microservices. It will reason about the possibilities and outline situations where they are applicable. All that while keeping in mind various system design constraints that tug at each other.

Inter-service communication and execution flow is a foundational decision for a distributed system. It can be synchronous or asynchronous in nature. Both the approaches have their trade-offs and strengths. This blog attempts to dissect various choices in detail and understand their implications.

Dimensions

Each implementation style has trade-offs. At the same time, there can be various dimensions to a system under consideration. Evaluating trade-offs against these constraints can help us reason about approaches and applicability. There are various dimensions of a system that impact the execution flow and the communication style of a system. Let’s look at some of them.

Consumers

Consumers of a system can be external programs, web/mobile interfaces, IoT devices etc. Consumer applications often deal with the server synchronously and expect the interface to support that. It is also desirable to mask the complexity of a distributed system with a unified interface for consumers. So it is imperative that our communication style allows us to facilitate it.

Workflow Management

With many participating services, the management of a business-workflow is crucial. It can be implicit and can happen at each service and therefore remain distributed across services. Alternatively, it can be explicit. An orchestrator service can own up the responsibility for orchestrating the business-flows.

The orchestration is a combination of two things. A workflow specification, that lays out the sequence of execution and the actual calls to the services. The latter is tightly bound to the communication paradigm that the participating services follow. Communication style and execution flow drive the implementation of an orchestrator.

A third option is an event-choreography based design. This substitutes an orchestrator via an event bus that each service binds to.

All these are mechanisms to manage a workflow in a system. We will cover workflow management in detail, later in this series. However, we will consider constraints associated with them in the current context as we evaluate and select a communication paradigm.

Read/Write Frequency Bias

Read/Write frequency of the system can be a crucial factor in its architecture. A read-heavy system expects a majority of operations to complete synchronously. A good example would be a public API for a weather forecast service that operates at scale. Alternatively, a write-heavy system benefits from asynchronous execution. An example would be a platform where numerous IoT devices are constantly reporting data. And of course, there are systems in between. Sometimes it is useful to favor a style because of the read-write skew. At other times, it may make sense to split reads and writes into separate components.

As we look through various approaches we need to keep these constraints in perspective. These dimensions will help us distill the applicability of each style of implementation.

Synchronous

Synchronous communication is a style of communication where the caller waits until a response is available. It is a prominent and widely used approach. Its conceptual simplicity allows for a straightforward implementation making it a good fit for most of the situations.

Synchronous communication is closely associated with HTTP protocol. However, other protocols remain an equally reasonable way to implement synchronous communication. A good example of an alternative is RPC calls. Each component exposes a synchronous interface that other services call.

An interceptor near the entry point intercepts the business flow request. It then pushes the request to downstream services. All the subsequent calls are synchronous in nature. These calls can be parallel or sequential until processing is complete. Handling of the calls within the system can vary in style. An orchestrator can explicitly orchestrate all the calls. Or calls can percolate organically across components. Let’s look at few possible mechanisms.

Variations

Within synchronous systems, there are several approaches that an architecture can take. Here is a quick rundown of the possibilities.

De-Centralized and Synchronous

A de-centralized and synchronous communication style intercepts a flow at the entry point. The interceptor forwards the request to the next step and awaits a response. This cycle continues downstream until all services have completed their execution. Each service can execute one or more downstream service sequentially or in parallel.

While the implementation is straightforward, the flow details remain distributed in the system. This results in coupling between components to execute a flow.

The calls remain synchronous throughout the system. Thus, the communication style can fulfill the expectations of a synchronous consumer. Because of distributed workflow nature, the approach doesn’t allow room for flexibility. It is not well suited for a complex workflow that is susceptible to change. Since each request to the system can block services simultaneously, it is not ideal for a system with high read/write frequency.

Orchestrated, Synchronous, and Sequential

A variation of synchronous communication is with a central orchestrator. The orchestrator remains the intercepting service. It processes the incoming request with workflow definition and forwards it to downstream services. Each service, in turn, responds back to the orchestrator. Until the processing of a request, orchestrator keeps making calls to services.

Among the constraints listed at the beginning, the workflow management is more flexible in this approach. The workflow changes remain local to orchestrator and allow for flexibility. Since the communication is synchronous, synchronous consumers can communicate without a mediating component. However, orchestrator continues to hold all active requests. This burdens orchestrator more than other services. It is also susceptible to being a single point of failure. This style of architecture is still suitable for a read-heavy system.

Orchestrated, Synchronous, and Parallel

A small improvement on the previous approach is to make independent requests parallel. This leads to higher efficiency and performance. Since this responsibility falls within the realms of orchestration, it is easy to do. Workflow management is already centralized. It only requires changes in the declaration to distinguish between parallel and sequential calls.

This can allow for faster execution of a flow. With shorter response times, orchestrator can have a higher throughput.

Workflow management is more complex than the previous approach. It still might be a reasonable tradeoff since it improves both throughput and performance. All that, while keeping the communication synchronous for consumers. Due to its synchronous nature, the system is still better for a read-heavy architecture.

Trade-Offs

Although synchronous calls are simpler to grasp, debug and implement, there are certain trade-offs which are worth acknowledging in a distributed setup.

Balanced Capacity

It requires a deliberate balancing of the capacity for all the services. A temporary burst at one component can flood other services with requests. In asynchronous style, queues can mitigate temporary bursts. Synchronous communication lacks this mediation and requires service capacity to match up during bursts. Failing this, a cascading failure is possible. Alternatively, resilience paradigms like circuit breakers can help mitigate a traffic burst in a synchronous system.

Risk of Cascading Failures

Synchronous communication leaves upstream services susceptible to cascading failure in a microservices architecture. If downstream services fail or worst yet, take too long to respond back, the resources can deplete quickly. This can cause a domino effect for the system. A possible mitigation strategy can involve consistent error handling, sensible timeouts for connections and enforcing SLAs. In a synchronous environment, the impact of a deteriorating service ripple through other services immediately. As mentioned previously, prevention of cascading errors can happen by implementing a bulkhead architecture or with circuit breakers.

Increased Load Balancing & Service Discovery Overhead

The redundancy and availability needs for a participating service can be addressed by setting them up behind a load balancer. This adds a level of indirection per service. Additionally, each service needs to participate in a central service discovery setup. This allows it to push its own address and resolve the address of the downstream services.

Coupling

A synchronous system can exhibit much tighter coupling over a period of time. Without abstractions in between, services bind directly to the contracts of the other services. This develops a strong coupling over a period of time. For simple changes in the contract, the owning service is forced to adopt versioning early on. Thereby increasing the system complexity. Or it trickles down a change to all consumer services which are coupled to the contract.

With emerging architectural paradigms like service mesh, it is possible to address some of the stated issues. Tools like Istio, Linkerd, Envoy, etc. allow for service mesh creation. This space is maturing and remains promising. It can help build systems that are synchronous, more decoupled and fault tolerant.

Asynchronous

Asynchronous communication is well suited for a distributed architecture. It removes the need to wait for a response thereby decoupling the execution of two or more services. Implementation of asynchronous communication is possible with several variations. Direct calls to a remote service over RPC (for instance, grpc) or via a mediating message bus are few examples. Both orchestrated message passing and event choreography use message bus as a channel.

One of the advantages of a central message bus is consistent communication and message delivery semantics. This can be a huge benefit over direct asynchronous communication between services. It is common to use a medium like a message bus that facilitates communication consistently across services. The variations of asynchronous communications discussed below will assume a central message pipeline.

Variations

The asynchronous communication deals better with sporadic bursts of traffic. Each service in the architecture either produces messages, consumes messages or does both. Let’s look at different structural styles of this paradigm.

Choreographed Asynchronous Events

In this approach, each component listens to a central message bus and awaits an event. The arrival of an event is a signal for execution. Any context needed by execution is part of the event payload. Triggering of downstream events is a responsibility that each service owns. One of the goals in event-based architecture is to decouple the components. Unfortunately, the design needs to be responsible to cater to this need.

A notification component may expect an event to trigger an email or SMS. It may seem pretty decoupled since all that the other services need to do is produce the event. However, someone does need to own the responsibility of deciding type of notification and content. Either notification can make that decision based on an incoming event info. If that happens then we have established a coupling between notifications and upstream services. If upstream services include this as part of the payload, then they remain aware of flows downstream.

Even so, event choreography is a good fit for implicit actions that need to happen. Error handling, notifications, search-indexing etc.

It follows a decentralized workflow management. The architecture scales well for a write-heavy system. The downside is that synchronous reads need mediation and workflow is spread through the system.

Orchestrated, Asynchronous, and Sequential

We can borrow a little from our approach in orchestrated synchronous communication. We can build an asynchronous communication with orchestrator at the center.

Each service is a producer and consumer to the central message bus. Responsibilities of orchestrator involve routing messages to their corresponding services. Each component consumes an incoming event or message and produces the response back on the message queue. Orchestrator consumes this response and does transformation before routing ahead to next step. This cycle continues until the specified workflow has reached its last state in the system.

In this style, the workflow management is local to the orchestrator. The system fares well with write-heavy traffic. And mediation is necessary for synchronous consumers. This is something that is prevalent in all asynchronous variations.

The solution to choreography coupling problem is more elegant in the orchestrated system. The workflow is with orchestrator in this case. A rich workflow specification can capture information like notification type and content template. Any changes to workflow remain with orchestrator service.

Hybrid With Orchestration and Event Choreography

Another successful variation is hybrid systems with orchestration and event choreography both. The orchestration is excellent for explicit flow execution, while choreography can handle implicit execution. Execution of leaf nodes in a workflow can be implicit. Workflow specification can facilitate emanation of events at specific steps. This can result in the execution of tasks like notifications, indexing, et-cetera. The orchestration can continue to drive explicit execution.

This amalgamation of two approaches provides best of both worlds. Although, there is a need for precaution to ensure they don’t overlap responsibilities and clear boundaries dictate their functioning.

Overview

Asynchronous style of architecture addresses some of the pitfalls that synchronous systems have. An asynchronous set-up fares better with temporary bursts of requests. Central queues allow services to catch up with a reasonable backlog of requests. This is useful both when a lot of requests come in a short span of time or when a service goes down momentarily.

Each service connects to a message queue as a consumer or producer. Only the message queue requires service discovery. So the need for a central service discovery solution is less pressing. Additionally, since multiple instances of a service are connected to a queue, external load balancing is not required. This prevents another level of indirection that otherwise, load balancer introduces. It also allows services to linear scale seamlessly.

Trade-Offs

Service flows that are asynchronous in nature can be hard to follow through the system. There are some trade-offs that a system adopting asynchronous communication will make. Let’s look at some of them.

Higher System Complexity

Asynchronous systems tend to be significantly more complex than synchronous ones. However, the complexity of system and demands of performance and scale are justified for the overhead. Once adopted both orchestrator and individual components need to embrace the asynchronous execution.

Reads/Queries Require Mediation

Unless handled specifically synchronous consumers are most affected by an asynchronous architecture. Either the consumers need to adapt to work with an asynchronous system, or the system should present a synchronous interface for the consumers.

Asynchronous architecture is a natural fit for the write-heavy system. However, it needs mediation for synchronous reads/queries. There are several ways to manage this need. Each one has certain complexity associated with it.

Sync Wrapper

Simplest of all approaches is building a sync wrapper over an async system. This is an entry point that can invoke asynchronous flows downstream. At the same time, it holds the request awaiting until the response returns or a timeout occurs. A synchronous wrapper is a stateful component. An incoming request ties itself to the server it lands on. The response from downstream services needs to arrive at the server where original request is waiting. This isn’t ideal for a distributed system, especially one that operates at scale. However, it is simple to write and easy to manage. For a system with reasonable scaling and performance needs it can fit the bill. A sync wrapper should be a consideration before a more drastic restructuring.

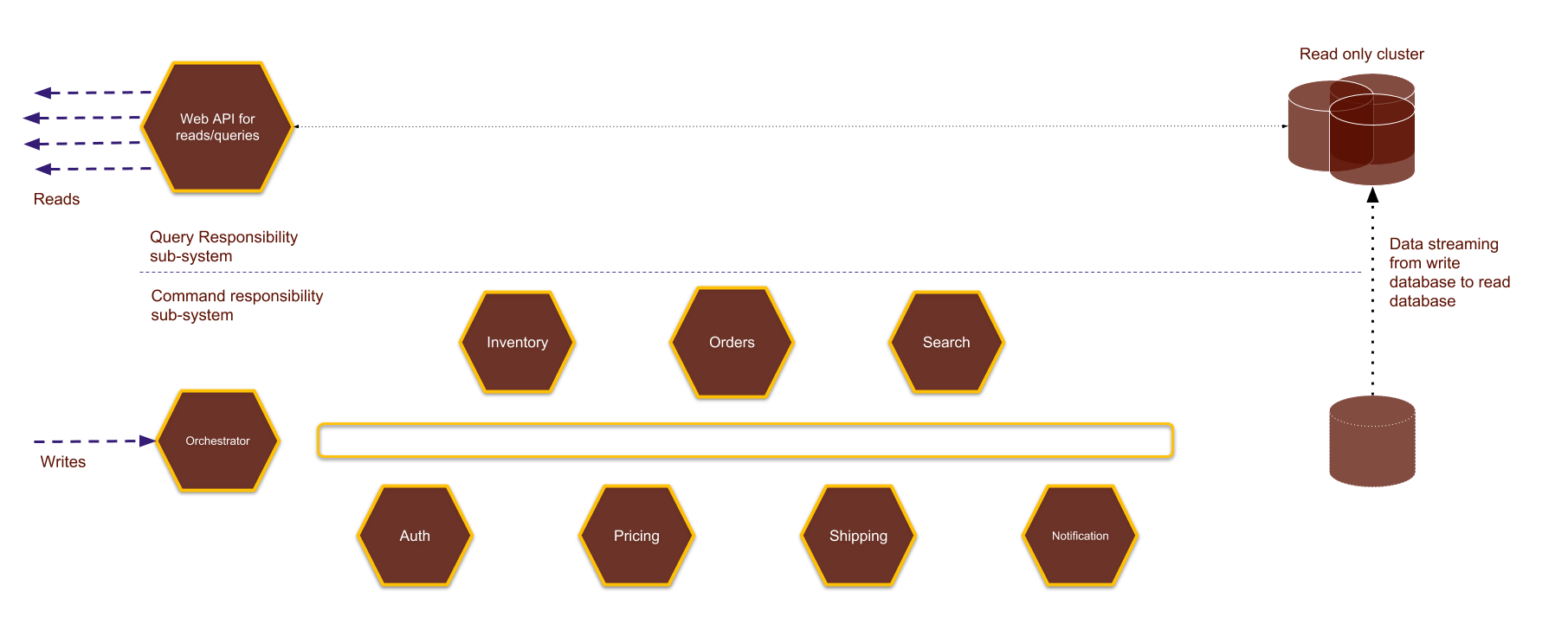

CQRS

CQRS is an architectural style that separates reads from writes. CQRS brings a significant amount of risk and complexity to a system. It is a good fit for systems that operate at scale and requite heavy reads and writes. In CQRS architecture, data from write database streams to a read database. Queries run on a read-optimized database. Read/Write layers are separate and the system remains eventually consistent. Optimization of both the layers is independent. A system like this is far more complex in structure but it scales better. Moreover, the components can remain stateless (unlike sync wrappers).

Dual Support

There is a middle ground here between a sync wrapper and a CQRS implementation. Each service/component can support synchronous queries and asynchronous writes. This works well for a system which is operating at a medium scale. So read queries can hop between components to finish reads synchronously. Writes to the system, on the other hand, will flow down asynchronous channels. There is a trade-off here though. The optimization of a system for both reads and writes independently is not possible. Something, that is beneficial for a system operating at high traffic.

Message Buses Are a Central Point of Failure

This is not a trade-off, but a precaution. In the asynchronous communication style, message bus is the backbone of the system. All services constantly produce-to and consume-from the message bus. This makes the message bus the Achilles heel of the system as it remains a central point of failure. It is important for a message bus to support horizontal scaling otherwise it can work against the goals of a distributed system.

Eventual Consistency

An asynchronous system can be eventually consistent. It means that results in queries may not be latest, even though the system has issued the writes. While this trade-off allows the system to scale better, it is something to factor-in into system’s design and user experience both.

Hybrid

It is possible to use both asynchronous and synchronous communication together. When done the trade-offs of both approaches overpower their advantages. The system has to deal with two communication styles interchangeably. The synchronous calls can cascade degradation and failures. On the other hand, the asynchronous communication will add complexity to the design. In my experience, choosing one approach in isolation is more fruitful for a system design.

Verdict

Martin Fowler has a great blog on approaching the decision to build microservices. Once decided, a microservice architecture requires careful deliberation around its execution flow style. For a write, heavy system asynchronous is the best bet with a sync-over-async wrapper. Whereas, for a read-heavy system, synchronous communication works well.

For a system that is both read and write heavy, but has moderate scale requirements, a synchronous design will go a long way in keeping the design simple. If a system has significant scale and performance needs, asynchronous design with CQRS pattern might be the way to go.

Published at DZone with permission of Priyank Gupta. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments