Overview of C# Async Programming

This article reviews the various threads and thread pools solutions in the .NET framework. Read on to find out more!

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For Free

I recently found myself explaining the concept of thread and thread pools to my team. We encountered a complicated threads-problem in our production environment that led us to review and analyze some legacy code. Although it threw me back to the basics, it was beneficial to review .NET capabilities and features in managing threads, which mainly reflected how .NET evolved significantly throughout the years. With the new options available today, tackling the production problem is much easier to cope with.

TL;DR

So, this circumstance led me to write this blog-post to go through the underlying foundations and features of threads and thread pools:

- Thread pool concept

- Examples for thread pools executions in .NET

- Task Parallel Library features (some uncommon ones)

- Task-based Asynchronous Pattern (TAP)

The Threads .NET libraries are a vast topic, with many nuances; so, to keep this article as readable and concise as possible. However, I placed some links to external resources to delve more into some of the topics.

A Short Review of .NET Thread Pools

Let’s start with a high-level review of threads; what is the incentive to use threads? Well, ultimately, it is freeing local resources and eliminate bottlenecks. The class System.Threading.Thread is the most basic way to run a thread, but it comes with a cost. The creation and destruction of threads incur high resource utilization, mainly CPU overhead. To avoid this penalty, which can be expensive in terms of performance when threads are being created and destroyed extensively, .NET has presented the ThreadPool class. This class allocates a certain number of threads and manages them for you.

Although ThreadPool has advantagest is better to stick to the good old Thread creation practice in some scenarios in some scenarios. It is especially relevant when you need finer control on the thread execution. For example, setting the thread to be a foreground thread, the ThreadPool instantiates only background threads, so you should use the Thread object when a foreground thread is required (read here about the meaning of background and foreground threads). Other scenarios are setting the thread’s priority or aborting a specific thread. This low-level control cannot be done if you use a ThreadPool object.

The Task library is based on the thread pool concept, but let’s review shortly other implementations of thread pools before diving into it before diving into it.

Creating Thread Pools

By definition, a thread is an expensive operating system object. Using a thread pool reduces the performance penalty by sharing and recycling threads; it exists primarily to reuse threads and to ensure the number of active threads is optimal. The number of threads can be set to lower and upper bounds. The minimum applies to the minimum number of threads the ThreadPool maintains, even on idle. When an upper limit is hit, all new threads are queuing until another thread is evicted and allows a new thread to start.

C# allows the creation of thread pools by calling on of the following:

- ThreadPool.QueueUserWorkItem

- Asynchronous delegate

- Background worker

- Task Parallel Library (TPL)

A trivia comment: to identify whether a single thread is part of a thread pool or not, run the boolean property Thread.CurrentThread.IsThreadPool.

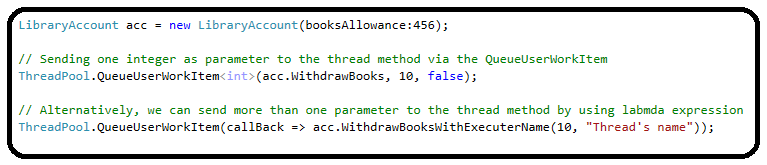

The ThreadPool Class

Using the ThreadPool class is the classic clean approach to create a thread in a thread, calling ThreadPool.QueueUserWorkItem method will create a new thread and add it to a queue. After queuing the work-item, the method will run when the thread pool is available; if the thread pool is occupied or reach its upper limit, the thread will wait.

The ThreadPool object can be limit the number of threads running under it; it can be configured by the calling ThreadPool.SetMaxThreadmethod. This method's executionmethod's execution is ignored(return False) if the parameters are lesser than the number of CPUs on the machine. To obtain the number of CPUs of the machine, call Environment.ProcessorCount.

//threadPoolMax= Environment.ProcessorCount;

result = ThreadPool.SetMaxThreads(threadPoolMax, threadPoolMax);

In essence, creating threads using the ThreadPool class is quite easy, but it has some limitations. Passing parameters to the thread method are quite a rigid way since the WaitCallback delegate receives only one argument (an object); however, the QueueUserWorkItem has an overload that can receive the generic value, but it is still only one parameter. We can use a lambda expression to bypass this limitation and send the parameters directly to the method of the thread:

Another missing feature in ThreadPool class is signaling when all threads in the thread pool have finished. The ThreadPool class does not expose an equivalent method to Task.WaitAll(), so it must be done manually. The method below shows how to pause the main thread until all threads are done; it uses a CountdownEvent object to count the number of active threads.

Using the CountdownEvent object to identify when the execution of the threads has ended:

x

[Theory]

[InlineData(1500, 300)]

[InlineData(1200, 160)]

public void ThreadPoolWithCounter(int booksAllowance, int threadsToRun)

{

// Initialize counter with 1, otherwise, the AddCount method will throw an error (the counter is signaled and cannot be incremented).

using (CountdownEvent cde = new CountdownEvent(1))

{

ManualResetEvent manualResetEvent = new ManualResetEvent(false);

LibraryAccount account = new LibraryAccount(booksAllowance: booksAllowance);

for (int i = 0; i < threadsToRun; i++)

{

bool enqueued = ThreadPool.QueueUserWorkItem(delegate

{

// Increase the counter

cde.AddCount();

Trace.WriteLine(message: $"Increase CountDown, current count: {cde.CurrentCount}");

// Execute the business logic: a thread-safe withdraw books (implements lock internally)

account.WithdrawBooksWithExecuterName(10, "Thread_" + DateTime.Now.Ticks);

// Decrease the counter

cde.Signal();

Trace.WriteLine(message: $"Decrease CountDown, current count: {cde.CurrentCount}");

// Signal that at least one thread is executed.

manualResetEvent.Set();

});

}

// ensure that at least one thread was created

manualResetEvent.WaitOne();

// Decrease the counter (as it was initialized with the value 1).

cde.Signal();

// Wait until the counter is zero.

cde.Wait();

Trace.WriteLine(message: $"All threads are finished, current count: {cde.CurrentCount}");

}

}

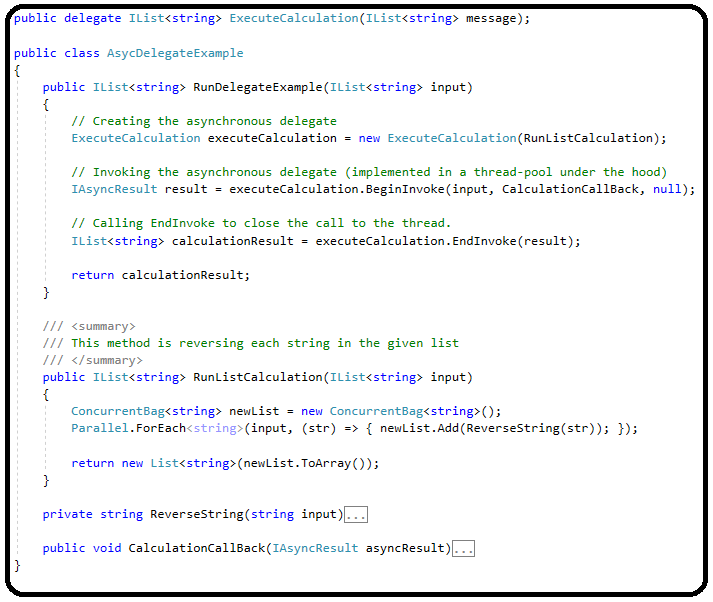

Asynchronous Delegates

This is the second mechanism that uses a thread pool; the .NET asynchronous delegates run on a thread pool under the hood. Invoking a delegate asynchronously allows sending parameters (input and output) and receiving results more flexibly than using the Thread class, which receives a ParameterizedThreadStart delegate that is more rigid than a user-defined delegate. The sample code below exemplifies how to initiate and run delegate in an asynchronous way:

Another trivia fact: the asynchronous delegate feature is not supported in .NET Core; the system will throw a System.PlatformNotSupportedExceptionexception when running on this platform. This is not a real limitation; there are other new ways to generate threads today.

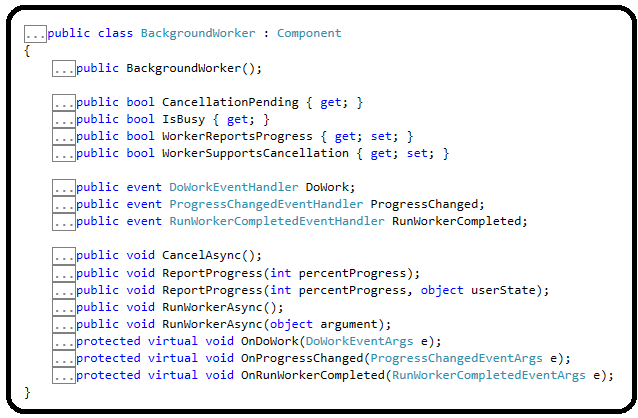

The Background Worker

The BackgroundWorker class (under System.ComponentModel namespace) uses thread pool too. It abstracts the thread creation and monitoring process when exposing events that report the thread’s process, making this class suitable for GUI responses, for example, reflecting a long-running process that executes in the background. By wrapping the System.Threading.Thread class, it is much easier to interact with the thread.

The BackgroundWorker class exposes two main events: ProgressChanged and RunWorkerCompleted; the first is triggered by calling the ReportProgress method.

After reviewing three ways to run threads based on thread pools, let’s dive into the Task Parallel Library.

Task Parallel Library Features

The Task Parallel Library (TPL) was introduced in .NET 4.0 as a significant improvement in running and managing threads compared to the existing System.Threading the library earlier; this was the big news in its debut.

In short, the Task Parallel Library (TPL) provides more efficient ways to generate and run threads than the traditional Thread class. Behind the scenes, Tasks objects are queued to a thread pool. This thread pool is enhanced with algorithms that determine and adjust the number of threads to run and provide load balancing to maximize throughput. These features make the Tasks relatively lightweight and handle effectively threads than before.

The TPL syntax is more friendly and richer than the Thread library; for example, defining fine-grained parallelism is much easier than before. Among its new features, you can find partitioning of the work, taking care of state management, scheduling threads on the thread pool, using callback methods, and enabling continuation or cancellation of tasks.

The main class in the TPL library is Task; it is a higher-level abstraction of the traditional Thread class. The Task class provides more efficient and more straightforward ways to write and interact with threads. The Task implementation offers fertile ground for handling threads.

The basic constructor of a Task object instantiation is the delegate Action, which returns void and accepts no parameters. We can create a thread that takes parameters and bypass this limitation with a constructor that accepts one generic parameter, but it is still too rigid (Task(Action<object> action, object parameter). Therefore, an easier instantiation would be an empty delegate with the explicit implementation of the thread.

LibraryAccount libraryAccount = new LibraryAccount(booksAllowance);

Task task = new Task(()=>

libraryAccount.WithdrawBooks(booksToWithdraw)

);

Let’s review some features the Task library presents:

- Tasks continuation

- Parallelling tasks

- Canceling tasks

- Synchronizing tasks

- Converging tasks back to the calling thread

Feature #1: Tasks Continuation

The Task implementation synchronizes the execution of threads easily, by setting execution order or canceling tasks.

Before using the Task library, we had to use callback methods, but with TPL, it is much more comfortable. A simple way to chain threads and create a sequence of execution can be achieved by using Task.ContinueWith method. The ContinueWith method can be chained to the newly created Task or defined on a new Task object.

Another benefit of using the the the ContinueWith method is passing the previous task as a parameter, which enables fetching the result and processingprocessing it.

The ContinueWith method accepts a parameter that facilitates the execution of the subsequent thread, TaskContinuationOptions, that some of its continuation options I find very useful:

- OnlyOnFaulted/NotOnFaulted (the continuing Task is executed if the previous thread has thrown an unhandled exception failed or not);

- OnlyOnCanceled/NotOnCanceled (the continuing Task is executed if the previous thread was canceled or not).

You can set more than one option by defining an OR bitwise operation on the TaskContinuationOptions items.

xxxxxxxxxx

[Theory]

[InlineData(155, 34)]

public void TasksContinueWith(int booksAllowance, int booksToWithdraw)

{

// Initiate a library account object

LibraryAccount libraryAccount = new LibraryAccount(booksAllowance);

Task<int> task = Task.Factory.StartNew<int>(() =>{

// The first task withdraws books

libraryAccount.WithdrawBooks(booksToWithdraw);

return libraryAccount.BorrowedBooksCount;

})

.ContinueWith<int>((prevTask) => {

// Fetching the result from the previous task

int booksInventory = prevTask.Result;

Trace.WriteLine($"Current books inventory count {booksInventory}");

// Return the books back to the library

libraryAccount.ReturnBooks(booksToWithdraw);

return libraryAccount.BorrowedBooksCount;

}, // Set the conditions when to continue the subsequent task

TaskContinuationOptions.NotOnFaulted |

TaskContinuationOptions.NotOnCanceled |

TaskContinuationOptions.OnlyOnRanToCompletion);

// Wait for the task to end before continuing the main thread.

task.Wait();

// The actual number of books should remain the same

Assert.Equal(task.Result, booksAllowance);

}

Besides calling the ContinueWith method, there are other options to run threads sequentially. The TaskFactory class contains other implementations to continue tasks, for example, ContinueWhenAll or ContinueWhenAny methods. The ContinueWhenAll method creates a continuation Task object that starts when a set of specified tasks has been completed. In contrast, the ContinueWhenAny method creates a new task that will begin upon completing any task in the set that was provided as a parameter.

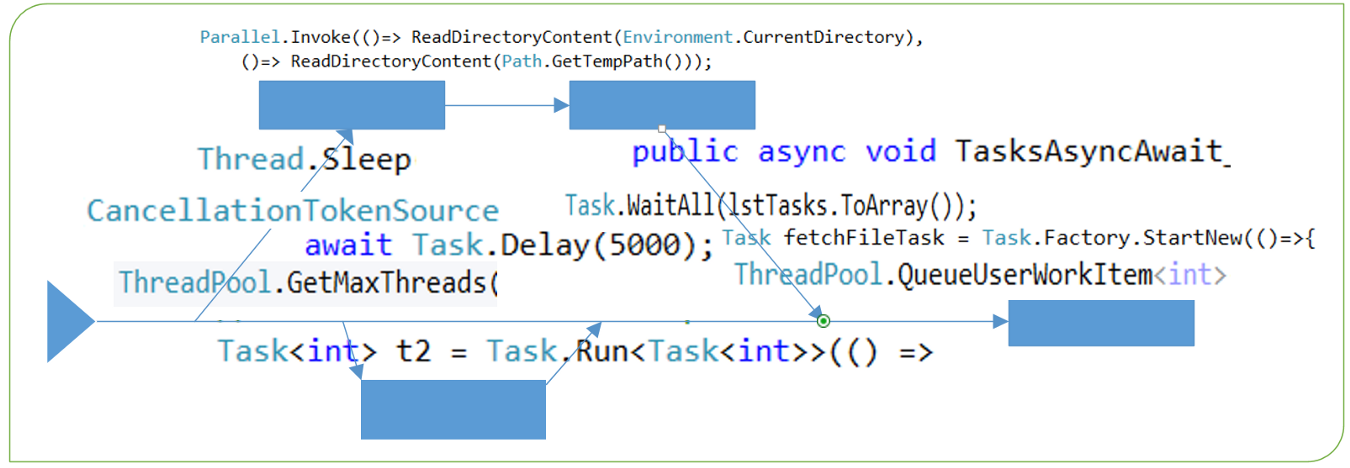

Feature #2: Parallelling Tasks

The Task Library allows running tasks in parallel after defining them together. The method Parallel.Invoke runs tasks given as arguments; the methodsTasParallel.ForEach and TasParallel.For run tasks in a loop.

This is an elegant approach to divide the execution resources; however, it may not be the fastest way to run your business logic (see the caveats section at the end of this article).

xxxxxxxxxx

[Theory]

[MemberData(nameof(TestDataMember))]

public void RunParallel()

{

// Run the two tasks in parallel.

Parallel.Invoke(()=>

ReadDirectoryContent(Environment.CurrentDirectory),

()=> ReadDirectoryContent(Path.GetTempPath()));

// A local function

void ReadDirectoryContent(string path)

{

string[] files = Directory.GetFiles(path);

// Print each file is a separate task

Parallel.ForEach<string>(files, (file) => {

Trace.WriteLine($"Found file: '{file}");

});

}

}

The exceptions during the execution of the methods For, ForEach, or Invoke are collated until the tasks are completed and thrown as an AggregateException exception.

Feature #3: Cancelling Tasks

The framework allows canceling tasks from the outside. It is implemented by injecting a cancellation token object to a task before its execution. This mechanism facilitates shutting down a thread gracefully after signaling a request to cancel was raisedraised, as opposed to Thread.Abort method that kills the thread abruptly.

However, there’s a tricky part; the thread is aware of this cancellation only when checking the property IsCancellationRequested, and thus it will not work without checking this property’s value deliberately. Moreover, the thread will continue its execution regularly and retain its Running status until the thread ends, unless an exception is thrown.

The C# test method below demonstrates this flow while focusing on the thread’s end status and the Wait method. This is quite a long and convoluted example, so I highlight the important pieces:

Firstly, notice the nuances of throwing exceptions inside the thread once the IsCancellationRequested equals True; if the exception is OperationCancelException, the thread’s state becomes Cancelled, but if another exception is thrown, then the thread’s state is Faulted.

Secondly, the method Wait can be overloaded with the cancellation token; when calling Wait(CancellationToken) , it returns when the token is canceled, regardless of throwing an exception, whereas calling the parameterless methodWait() returns only when the thread’s execution has finished (with or without exception). This behavior also affects the exception handling flow.

To grasp this topic completely, you can play with the example below and manipulate its flow and see how the state of the thread changes. This example is a bit long, but it unfolds the different scenarios and results when canceling tasks. I used the xUnit MemebrData attribute to generate the various test scenarios.

xxxxxxxxxx

/* See below the definitions of the test scenarios*/

[Theory]

[MemberData(nameof(CancellationTestScenarios))]

public void TasksCancellation_Test(int booksAllowance, int booksToWithdraw, string scenarioDescription, TestScenario testScenario, TaskStatus expectedStatus)

{

string testParameters = $@"Initial books allowance: { booksAllowance}, withdraw: { booksToWithdraw}

test scenario: { scenarioDescription}, expected result: { expectedStatus}";

Exception caughtException = null;

Logger.Log($@">>> Starting a new test --> {testParameters}");

LibraryAccount libraryAccount = new LibraryAccount(booksAllowance);

using (CancellationTokenSource source = new CancellationTokenSource())

{

CancellationToken cancellationToken = source.Token;

cancellationToken.Register(OnCancellationOccurred, null);

// Start the task after 5 seconds delay

Task taskWithdrawBooks = Task.Delay(5000).ContinueWith(_ =>

{

// if the thread wasn't canceled, the execution will continue normally.

cancellationToken.ThrowIfCancellationRequested();

while (libraryAccount.IsWithdrawAllowed(booksToWithdraw))

{

//Trace.WriteLine($"Working: {DateTime.Now.ToString("dd/MM/yyyy hh:mm:ssss")}");

libraryAccount.WithdrawBooks(booksToWithdraw);

//Trace.WriteLine($"Current books inventory count {libraryAccount.BorrowedBooksCount}");

// check if a cancellation request was made.

if (cancellationToken.IsCancellationRequested)

{

Logger.Log("Received a cancellation request");

// Throws OperationCancelException and stops the thread;

// thus, better to clean here all the thread's resources before the throwing the exception.

if ((testScenario & TestScenario.ThrowErrorAfterCancellation) != 0)

{

cancellationToken.ThrowIfCancellationRequested();

}

// Can throw other exception too, however the thread's state won't be set to Cancel, but Faulted.

if ((testScenario & TestScenario.ThrowGenerarExceptionAfterCancellation) != 0)

{

throw new InvalidDataException("a random exception");

}

}

Thread.Sleep(1000);

}

}, cancellationToken);

// Another task to print the status of the Withdraw books task.

Task printTaskStatus = Task.Factory.StartNew(() =>

{

TaskStatus prev = taskWithdrawBooks.Status;

Logger.Log($"+++ The task status: {taskWithdrawBooks.Status}");

while (taskWithdrawBooks.Status != TaskStatus.RanToCompletion)

{

if (taskWithdrawBooks.Status != prev)

{

prev = taskWithdrawBooks.Status;

Logger.Log($"+++ The task status has changed to: {taskWithdrawBooks.Status}");

}

}

});

// Changing the token's status to Cancel.

//Task.Delay(10000).ContinueWith(_=> { source.Cancel(false); });

source.CancelAfter(15000);

try

{

// This method returns if the task was canceled (calling Cancel method) or the thread has ended (gracefully or not).

if ((testScenario & TestScenario.WaitWithCancellationToken) != 0)

taskWithdrawBooks.Wait(cancellationToken);

// By calling Wait method without the CancellationToken, the Wait method won't return even if the thread was canceled.

// Although the thread was canceled, it will continue to run until completion.

// The method returns if the thread ended gracefully or not.

if ((testScenario & TestScenario.WaitWithoutCancellationToken) != 0)

taskWithdrawBooks.Wait();

}

catch (AggregateException e)

{

caughtException = e;

Logger.Log($"Exception #1: {nameof(e)} was thrown; error message: {e.Message}");

}

catch (OperationCanceledException e)

{

caughtException = e;

Logger.Log($"Exception #2: {nameof(OperationCanceledException)} was thrown; error message: {e.Message}");

}

// Wait for ensuring the thread's state is set.

Thread.Sleep(20000);

Logger.Log($@">>> Ending test --> {testParameters}");

// The status of the task will be set to Cancel only is a OperationCanceledException is thrown.

// Otherwise, the task status will remain Running or Faulted (if an other exception was thrown)

Assert.Equal(expectedStatus, taskWithdrawBooks.Status);

if ((testScenario & TestScenario.WaitWithCancellationToken) != 0)

{

// When calling a Wait method with the cancellation token, the exception will be caught regardless if the exception is thrown in the thread.

Assert.IsType<OperationCanceledException>(caughtException);

}

else if (((testScenario & TestScenario.WaitWithoutCancellationToken) != 0) &&

((testScenario & TestScenario.ThrowGenerarExceptionAfterCancellation) != 0 ||

((testScenario & TestScenario.ThrowErrorAfterCancellation) != 0)))

{

Assert.IsType<AggregateException>(caughtException);

}

else

{

// If no Wait method was called, even if an exception is thrown, it will not be caught; the main thread will continue without waiting for any returned status.

Assert.Null(caughtException);

}

}

// A local method for demonstration purposes.

void OnCancellationOccurred(object state)

{

Logger.Log($"The task was canceled, current books balance: {libraryAccount.BorrowedBooksCount}");

}

}

// Define an Enum to facilitate the various test scenarios

public enum TestScenario

{

ThrowErrorAfterCancellation = 1,

ThrowGenerarExceptionAfterCancellation = 2,

WaitWithCancellationToken = 4,

WaitWithoutCancellationToken = 8

}

// Define test scenarios to be passed into the test class

public static IEnumerable<object[]> CancellationTestScenarios()

{

// The structure of each test scenario is:

// (initial number of items), (number of items to reduce), (Scenario description), (TestScenario code), (Expected result)

yield return new object[] { 1550, 34, "Not calling wait, throw a cancellation exception", TestScenario.ThrowErrorAfterCancellation, TaskStatus.Canceled };

yield return new object[] { 1550, 34, "Not calling wait, throw a general exception", TestScenario.ThrowGenerarExceptionAfterCancellation, TaskStatus.Faulted };

yield return new object[] { 1550, 34, "Wait with cancellation, without any exception", TestScenario.WaitWithCancellationToken, TaskStatus.Running };

yield return new object[] { 1550, 34, "Wait with cancellation, throw a cancellation exception", TestScenario.WaitWithCancellationToken | TestScenario.ThrowErrorAfterCancellation, TaskStatus.Canceled };

yield return new object[] { 1550, 34, "Wait with cancellation, throw a general exception", TestScenario.WaitWithCancellationToken | TestScenario.ThrowGenerarExceptionAfterCancellation, TaskStatus.Faulted };

yield return new object[] { 200, 34, "Wait without cancellation, without any exception", TestScenario.WaitWithoutCancellationToken, TaskStatus.RanToCompletion };

yield return new object[] { 1550, 34, "Wait without cancellation, throw a cancellation exception", TestScenario.WaitWithoutCancellationToken | TestScenario.ThrowErrorAfterCancellation, TaskStatus.Canceled };

yield return new object[] { 1550, 34, "Wait without cancellation, throw a general exception", TestScenario.WaitWithoutCancellationToken | TestScenario.ThrowGenerarExceptionAfterCancellation, TaskStatus.Faulted };

}

Catching exceptions:

You may notice that when the Wait method was called, and an exception was thrown; the caught exception was AggregateException ; theWait collects exceptions into an AggregateException object, which holds the inner exceptions and the stack trace. That can be tricky when trying to unravel the true source of the exception.

Feature #4: Synchronising Tasks with TaskCompletionSource

This is another simple and useful feature for implementing an easy-to-use producer-consumer pattern. Synchronizing between threads has never been easier when using a TaskCompletionSource object; it is an out-of-the-box implementation for triggering a follow-up action after releasing the source object.

The TaskCompletionSource releases the Result task after setting the result (SetResult method) or canceling the task (simple SetCanceled or raising an exception, the SetException). Similar behavior can be achieved with EventWaitHandle, which simplements the abstract class WaitHandle; however, this pattern fits more for sequence operations, such assuch as, reading files, or fetching data from a remote source. Since we want to avoid holding our machine’s resources, triggering response is the more efficient solution.

The test method below exemplifies this pattern; the second task execution continues only after setting the first one.

xxxxxxxxxx

[Fact]

public void RunTaskCompleteSourceTest()

{

TaskCompletionSource<FileInfo> taskCompletionSource = new TaskCompletionSource<FileInfo>();

Task<FileInfo> anotherTask = taskCompletionSource.Task;

Task fetchFileTask = Task.Factory.StartNew(()=>{

FileInfo fileInfo = new FileInfo(Directory.GetFiles(Environment.CurrentDirectory)[0]);

taskCompletionSource.SetResult(fileInfo);

// Releasing the anotherTask.Result also be done by calling SetException or SetCancel

//taskCompletionSource.SetException(new InvalidOperationException("this action is illegal"));

// Will raise a TaskCanceledException since the task was canceled.

//taskCompletionSource.SetCanceled();

});

Task accessFileTask = Task.Factory.StartNew(() =>

{

// Calling the Result property is a blocking call; the thread continues after assigning the Result object,

// receiving an exception, or canceling the task.

FileInfo info = anotherTask.Result;

Trace.WriteLine($"Received file '{info.Name}, last modified {info.LastWriteTime}'");

// TODO: do something with the file

});

// Avoid exiting the test method before both tasks have finished

Task.WaitAll(fetchFileTask, accessFileTask);

}

Feature #5: Converging Back to The Calling Thread

On the same threads synchronization topic, the Task library enables several ways to wait until other tasks have finished their execution. This is a significant expansion of the usage of theThread.Join concept.

The methods Wait , WaitAll , and WhenAny are different options to hold the calling thread until other threads have finished.

The code snippet below demonstrates these methods:

x

[Theory]

[InlineData(456, 10)]

public async void TaskWaitOptions(int initialNumberOfBooks, int numberOfTasks)

{

Random rnd = new Random();

List<Task> lstTasks = new List<Task>();

LibraryAccount acc = new LibraryAccount(initialNumberOfBooks);

for (int i = 0; i < numberOfTasks; i++)

{

Task t = new Task(() =>

{

acc.WithdrawBooksWithExecuterName(rnd.Next(1, 12), "Thread_" + DateTime.Now.Ticks);

});

lstTasks.Add(t);

// Starting the task in various times

Task.Delay(rnd.Next(3000, 10000)).ContinueWith((p)=> { t.Start(); });

}

await Task.Delay(5000);

int index = Task.WaitAny(lstTasks.ToArray());

Trace.WriteLine($">>> The task in index {index} is completed; waiting for the rest to complete");

Task.WaitAll(lstTasks.ToArray());

Trace.WriteLine($">>> All the tasks were completed");

}

The methods WhenAll and WhenAny are a convolution of the WaitAll and WaiAny; these methods create a new Task upon return.

There is a difference between Task.Wait and Thread.Join although both block the calling thread until the other thread has concluded. This difference relates to the fundamental difference between Thread and Task; the latter runs in the background. Since Thread, by default, runs as a foreground thread, it may not be necessary to call Thread.Join to ensure it reaches completion before closing the main application. Nevertheless, there are cases the flow of the logic dictates a thread must be completed before moving on, and this is the place to call Thread.Join .

The Task library has many other capabilities that this article cannot include (I’m trying to keep you engaged). I'll leave you with one last useful feature related to the others mentioned in the article: scheduling tasks; it is explained in-depth on .NET documentation.

The Differences Between Thread.Sleep() and Task.Delay()

In some of the examples above, I used Thread.Sleep or Task.Delaymethods to hold the execution of the main thread or the side thread. Although it seems these two calls are equivalent, they are significantly different.

A call to Thread.Sleep freezes the current thread from all the executions since it runs synchronously, whereas calling to Task.Delay opens a thread without blocking the current thread (it runs asynchronously).

If you want the current thread to wait, you can call await Task.Delay() that opens a thread and returns when it has finished (along with decorating the calling method with the async keyword, see the next chapter). Again, it differs from Thread.Sleep that forces the current thread to halt all its executions.

Task-Based Asynchronous Pattern (TAP)

Async and await are keyword markers to indicate asynchronous operations; the await keyword is a non-blocking call that specifies where the code should resume after a task is completed.

The async/await syntax has been introduced with C# 5.0 and .NET Framework 4.5 . It allows writing asynchronous code that looks like synchronous code.

But how does async-await manage to do it? It’s nothing magical, just a little bit of syntactic sugar that verifies we receive the task's result when needed. The same result can be achieved by using ContinueWith and Result methods; however, it async/await allows using the return value easily in different locations in the code. That is the advantage of this pattern.

xxxxxxxxxx

[Theory]

[InlineData(456)]

public async void TasksAsyncAwait_Tests(int initialNumberOfBooks)

{

Random rnd = new Random();

LibraryAccount acc = new LibraryAccount(initialNumberOfBooks);

// Run t1, received its result (Task<int>)

Task<int> t1 = BorrowBooks(acc, nameof(t1));

// *********** First example ****************

// After completing t1, continue to another Task

int status = t1.ContinueWith<int>((prevTask) =>

{

Logger.Log($"After {nameof(t1)} execution, the books inventory is {prevTask.Result}");

// hold the execution of the thread to exemplify how the return is held

Thread.Sleep(2000);

return prevTask.Result;

}).Result;

// No need to call Wait, since Task.Result waits for the task to complete

//t1.Wait();

Logger.Log($">>> After running {nameof(t1)} and its successor: {status}");

// *********** Second example ****************

Task<int> t2 = Task.Run<Task<int>>(() =>

{

return BorrowBooks(acc, nameof(t2));

})

.Unwrap(); // return Task<int> instead of Task<Task<int>>

Task t3 = t2.ContinueWith((prevTask)=> {

Logger.Log($"After {nameof(t2)} execution, the books inventory is {prevTask.Result}");

// create another thread, without waiting for its return value.

BorrowBooks(acc, nameof(t3));

// To return from this thread only after completing the BorrowBook execution.

//BorrowBooks(acc, nameof(t3)).Wait();

});

// Waiting for t3, but the its inner thread might not be completed.

t3.Wait();

Logger.Log($">>> {nameof(t3)} completed");

// *********** Third example ****************

// Starting the task with delay

Task t4 = Task.Delay(rnd.Next(3000, 10000)).ContinueWith((p) => {

Task<int> innerTask = BorrowBooks(acc, nameof(t4));

innerTask.Wait();

});

Logger.Log($">>> Waiting for {nameof(t4)} to complete");

t4.Wait();

Logger.Log($">>> {nameof(t4)} completed");

Logger.Log($">>> The books inventory is {status}");

// *********** Forth example ****************

// Run the Task, wait until it completes, get its result.

status = await BorrowBooks(acc, "t5");

Logger.Log($">>> The library inventory after t5 is {status}");

// Calling await on t1 to fetch its result (in use-cases when it was still running in the background)

// This exemplifies the usefulness of await.

status = await t1;

Logger.Log($">>> Fetching the library inventory after t1: {status}");

// Local method: it runs a task that withdraws books from the library

Task<int> BorrowBooks(LibraryAccount account, string name)

{

return Task<int>.Run<int>(() =>

{

account.WithdrawBooksWithExecuterName(rnd.Next(1, 12), name + ":time="+DateTime.Now.Ticks);

return acc.BorrowedBooksCount;

});

}

}

These two keywords were designed to go together; if we declare a method is async without having any await then it will run synchronously. Note that a compilation error is raised when declaring await without mentioning the async keyword on the method (The ‘await’ operator can only be used within an async method).

Avoiding Deadlocks When using async/await

In some scenarios, calling await might cause a deadlock since the calling thread is waiting for a response. A detailed explanation can be found in this article (C# async-await: Common Deadlock Scenario).

As described in the article, an optional solution can be calling ConfigureAwait() method on the Task. This instructs the task to avoid capturing the calling thread and simply using the background thread to return the result. With that, the result is set, although the calling thread is blocked.

ValueTask — Avoiding Creation of Tasks

C# 7.0 has brought another evolvement to the Task library, the ValueTask<TResult> struct, that aims to improve performance in cases where there is no need to allocate Task<TResult>. The benefit of using the struct ValueTask is to avoid generating a Task object when the execution can be done synchronously while keeping the Task library API.

You can decide to return a ValueTask<TResult> struct from a method instead of allocating a Task object if it completed its successful execution synchronously; otherwise if your method completed asynchronously, a Task<TResult> object will be allocated wrapped with the ValueTask<TResult>. With that, you can keep the same API and treat ValueTask<TResult> as if it was Task<TResult>.

Keeping the same API is a significant advantage for keeping clean and consistent code. The ValueTask<TResult> can be awaited or converted to a Task object by calling AsTask method. However, there are some limitations and caveats when working with ValueTask. If you do not adhere to the behavior below, the results are undefined (based on .NET documentation):

- Calling

awaitmore than once. - Calling AsTask multiple times.

- Using

.Resultor.GetAwaiter().GetResult()when the operation hasn't been completed yet or using them multiple times. - Using more than one of these techniques to consume the instance.

You can read this article for further details.

To recap, when there is no need to allocate a new Task object, consider saving the cost of allocating it, and use ValueTask instead.

Caveat: Sometimes Threads Are Not The Ultimate Solution

After praising the usage of threads, there are some caveats before using Task objects ubiquitously. Threads are not necessarily more efficient than synchronous calls. Some jobs do not benefit from threads, whilethe same tasks can be executed faster if done synchronously.

Firstly, the thread mechanism has an overhead, and thus it might not be an efficient solution. This overhead can eliminate the threading advantage for some short-running tasks. Not only the length of the execution matters but also its algorithm. If the algorithm is sequential, then it is not optimal to distribute its execution across multiple threads.

Secondly, machine limitations should not be overlooked when using threads, better use a machine with a multiple-coremultiple-core CPU, which is very common these days. The number of running threads should not exceed the number of available cores; otherwise, the performance will degrade.

Thirdly, if the threads are consuming the same resource, we have shifted the problem to another bottleneck. For example, when our threads read from the same file system, they might be limited by the I/O throughput or the target machines’ RAM.

Last Words

Using threads is another tool in your arsenal as a developer, and like any other tool, it should be used wisely. It is a fundamental capability for executing logic; however, it comes with additional cost, but not only resources during execution time.

Writing and implementing threads add complexity across software development lifecycle phases; you have to invest more in each SDLC phase: developing, testing, implementing, and monitoring. Investing in monitoring is crucial for maintaining your product effectively. Do not neglect this phase, as you may find your resources drift to analyzing production logs, trying to figure out the flow of your logic in an intricate threads mesh.

Thank you for reading; I hope you find this blog-post interesting; your comments and responses are most welcome.

Happy coding!

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments