The Why and How of Microservice Messaging in Kubernetes

Struggling with connecting and maintaining microservices in Kubernetes? Let's look at the benefits and difficulties with messaging in Kubernetes.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeIntroduction

Struggling with connecting and maintaining your microservices in Kubernetes? As the number of microservices grows, the difficulty and complexity of maintaining your distributed fleet of services grows exponentially. Messaging can provide a clean solution to this issue, but legacy message queues come with their own set of problems.

In this article, I’ll share the benefits of messaging in Kubernetes and the difficulties that can come with legacy solutions. I'll also briefly look at KubeMQ, which attempts to address some of the traditional problems with messaging in Kubernetes.

Why Messaging in Kubernetes?

As a microservice-based architecture grows, it can be difficult to connect each of these distributed services. Issues of security, availability, and latency have to be addressed for each point-to-point interaction. Furthermore, as the number of services increases, the number of potential connections also grows. For example, consider an environment with only three services. These three services have a total of three potential connections:

However, as that increases to say five services, the number of potential connections increases to 10:

With 20 services, the number of potential connections is 190! For reference, see the table below:

# of Services |

3 |

5 |

20 |

n |

# of Connections |

3 |

10 |

190 |

n(n-1)/2 |

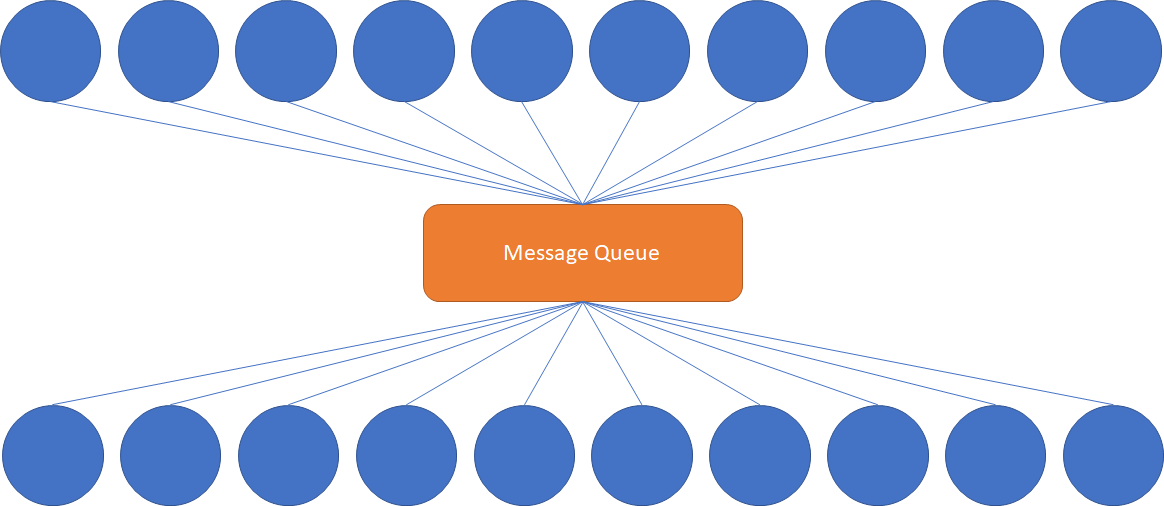

This is clearly not sustainable for organizations with a large portfolio of services. However, through the use of a message queue, we can centralize those connections. Since the number of connections is equal to the number of services, this results in a solution which scales linearly. See below:

For a large microservice fleet, this significantly simplifies the security and availability issues, as each microservice needs to communicate primarily with the message queue. This is the very reason implementing a message queue architecture is considered best practice when running large numbers of microservices in Kubernetes. As a result, the selection of the message queue is a critically important decision, as the entire architecture will depend on the reliability and scalability of that message queue.

Finally, deploying the message queue in Kubernetes allows you to avoid platform lock-in. There are a number of platform-specific messaging solutions from the major cloud providers, but running a platform-agnostic solution allows you to keep your microservices architecture consistent, regardless of your platform. Kubernetes is the de facto orchestration solution and has support from all major cloud providers.

Now that we’ve established why messaging is helpful, let’s dig a little deeper. This seems like such a simple solution, so what could be so hard about it?

What's hard about messaging in Kubernetes?

There are a number of pain points when attempting to run a message queue in Kubernetes. Let’s consider the differences between a typical microservice and your standard message queue. I’ve summarized some of the differences in the following table:

Typical microservice |

Legacy message queue |

Resource-light |

Resource-intensive |

Stateless |

Stateful |

Simple deployment |

Complex deployment |

Horizontally scalable |

Vertically scalable |

First, microservices are designed to be resource-light. This is in some ways a natural result of being a microservice—each service performs a single purpose, and thus can be smaller and more nimble. In contrast, legacy message queues are large, resource-intensive applications. The latest version of IBM MQ at time of writing has significant hardware requirements. For example, > 1.5 GB disk space and 3 GB of RAM.

Additionally, a typical microservice is stateless, as it does not contain any part of the state of the application in itself. However, many legacy message queues function effectively as databases and require persistent storage. Persistent storage in Kubernetes is best handled with the Persistent Volume API, but this requires workarounds for legacy solutions.

These differences in resource usage lead naturally to the next point—microservices are simple to deploy. Microservices are designed to deploy quickly and as part of a cluster. On the other hand, due to their resource-intensive nature, legacy message queues have complex deployment instructions and require a dedicated team to set up and maintain.

Next, microservices are designed to be horizontally scalable. Horizontal scaling is done through the deployment of additional instances of a service. This allows a service to scale nearly infinitely, have high availability, and is generally cheaper. In contrast, due to the aforementioned resource requirements and deployment pains, legacy message queues must be scaled vertically--in other words, a bigger machine. In addition to the physical limitations (a single machine can only be so powerful), larger machines are expensive.

These issues typically require significant investment and time to resolve, reducing the value that the message queue provides to your overall architecture. However, none of these issues are inherent to messaging; they are instead an artifact of when the major message queues were designed and conceived.

So how can we address these issues? Let’s take a look at one option: using a Kubernetes-native message queue such as KubeMQ.

A Kubernetes-native Approach

KubeMQ attempts to solve Kubernetes-related messaging issues. Let’s take a look at a few ways it does this.

First, it is Kubernetes-native, which means that it integrates well with Kubernetes and is simple to deploy as a Kubernetes cluster. Operators that allow you to automate tasks beyond what Kubernetes natively provides come with the product for lifecycle management. Cluster persistency is supported through both local volume and PVCs. Being Kubernetes-native also means that it is cloud-agnostic, and thus it can also be deployed on-premises or into hybrid cloud environments.

Additionally, it is lightweight—the Docker container is roughly ~30 MB, a far cry from the GB of required space from legacy solutions. This allows it to be deployed virtually anywhere and enables new use cases, such as edge deployments for Internet-of-Things device support. Despite its small size, it has support for a variety of messaging patterns.

Finally, it is extensible. Through the use of Bridges, Targets, and Sources, these pre-built connectors allow it to connect to a variety of other applications and services, reducing the need for custom integrations. Bridges allow KubeMQ clusters to pass messages between one another, enabling KubeMQ to connect various cloud, on-premises, and edge environments.

Since KubeMQ is small, you can try it out with a local installation of minikube or access to any other Kubernetes cluster.

Sign up for a (free) account and get a license token.

Run kubectl apply -f https://get.kubemq.io/deploy?token=<your-license-token>

You can verify the status of your cluster with kubectl get kubemqclusters -n kubemq. For more information, check out the official docs.

Summary

In this article, I reviewed the benefits of a message queue, looked at difficulties around implementing messaging in Kubernetes, and took a quick look at KubeMQ—a lightweight and Kubernetes-native solution that can provide several advantages over legacy solutions.

Published at DZone with permission of Michael Bogan. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments