Introduction to Java Bytecode

Follow along this deep dive into JVM internals and Java bytecode to see how you can disassemble your files for in-depth inspections.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeReading compiled Java bytecode can be tedious, even for experienced Java developers. Why do we need to know about such low-level stuff in the first place? Here is a simple scenario that happened to me last week: I had made some code changes on my machine a long time ago, compiled a JAR, and deployed it on a server to test a potential fix for a performance issue. Unfortunately, the code was never checked into a version control system, and for whatever reason, the local changes were deleted without a trace. After a couple of months, I needed those changes in source form again (which took quite an effort to come up with), but I could not find them!

Luckily the compiled code still existed on that remote server. So with a sigh of relief, I fetched the JAR again and opened it using a decompiler editor... Only one problem: The decompiler GUI is not a flawless tool, and out of the many classes in that JAR, for some reason, only the specific class I was looking to decompile caused a bug in the UI whenever I opened it, and the decompiler to crash!

Desperate times call for desperate measures. Fortunately, I was familiar with raw bytecode, and I'd rather take some time manually decompiling some pieces of the code rather than work through the changes and testing them again. Since I still remembered at least where to look in the code, reading bytecode helped me pinpoint the exact changes and construct them back in source form. (I made sure to learn from my mistake and preserve them this time!)

The nice thing about bytecode is that you learn its syntax once, then it applies on all Java supported platforms — because it is an intermediate representation of the code, and not the actual executable code for the underlying CPU. Moreover, bytecode is simpler than native machine code because the JVM architecture is rather simple, hence simplifying the instruction set. Yet another nice thing is that all instructions in this set are fully documented by Oracle.

Before learning about the bytecode instruction set though, let's get familiar with a few things about the JVM that are needed as a prerequisite.

JVM Data Types

Java is statically typed, which affects the design of the bytecode instructions such that an instruction expects itself to operate on values of specific types. For example, there are several add instructions to add two numbers: iadd, ladd, fadd, dadd. They expect operands of type, respectively, int, long, float, and double. The majority of bytecode has this characteristic of having different forms of the same functionality depending on the operand types.

The data types defined by the JVM are:

- Primitive types:

- Numeric types:

byte(8-bit 2's complement),short(16-bit 2's complement),int(32-bit 2's complement),long(64-bit 2's complement),char(16-bit unsigned Unicode),float(32-bit IEEE 754 single precision FP),double(64-bit IEEE 754 double precision FP) booleantypereturnAddress: pointer to instruction

- Numeric types:

- Reference types:

- Class types

- Array types

- Interface types

The boolean type has limited support in bytecode. For example, there are no instructions that directly operate on boolean values. Boolean values are instead converted to int by the compiler and the corresponding int instruction is used.

Java developers should be familiar with all of the above types, except returnAddress, which has no equivalent programming language type.

Stack-Based Architecture

The simplicity of the bytecode instruction set is largely due to Sun having designed a stack-based VM architecture, as opposed to a register-based one. There are various memory components used by a JVM process, but only the JVM stacks need to be examined in detail to essentially be able to follow bytecode instructions:

PC register: for each thread running in a Java program, a PC register stores the address of the current instruction.

JVM stack: for each thread, a stack is allocated where local variables, method arguments, and return values are stored. Here is an illustration showing stacks for 3 threads.

Heap: memory shared by all threads and storing objects (class instances and arrays). Object deallocation is managed by a garbage collector.

Method area: for each loaded class, it stores the code of methods and a table of symbols (e.g. references to fields or methods) and constants known as the constant pool.

A JVM stack is composed of frames, each pushed onto the stack when a method is invoked and popped from the stack when the method completes (either by returning normally or by throwing an exception). Each frame further consists of:

- An array of local variables, indexed from 0 to its length minus 1. The length is computed by the compiler. A local variable can hold a value of any type, except

longanddoublevalues, which occupy two local variables. - An operand stack used to store intermediate values that would act as operands for instructions, or to push arguments to method invocations.

Bytecode Explored

With an idea about the internals of a JVM, we can look at some basic bytecode example generated from sample code. Each method in a Java class file has a code segment that consists of a sequence of instructions, each having the following format:

opcode (1 byte) operand1 (optional) operand2 (optional) ...

That is an instruction that consists of one-byte opcode and zero or more operands that contain the data to operate.

Within the stack frame of the currently executing method, an instruction can push or pop values onto the operand stack, and it can potentially load or store values in the array local variables. Let's look at a simple example:

public static void main(String[] args) {

int a = 1;

int b = 2;

int c = a + b;

}In order to print the resulting bytecode in the compiled class (assuming it is in a file Test.class), we can run the javap tool:

javap -v Test.classAnd we get:

public static void main(java.lang.String[]);

descriptor: ([Ljava/lang/String;)V

flags: (0x0009) ACC_PUBLIC, ACC_STATIC

Code:

stack=2, locals=4, args_size=1

0: iconst_1

1: istore_1

2: iconst_2

3: istore_2

4: iload_1

5: iload_2

6: iadd

7: istore_3

8: return

...We can see the method signature for the main method, a descriptor that indicates that the method takes an array of Strings ([Ljava/lang/String; ), and has a void return type (V ). A set of flags follow that describe the method as public (ACC_PUBLIC) and static (ACC_STATIC).

The most important part is the Code attribute, which contains the instructions for the method along with information such as the maximum depth of the operand stack (2 in this case), and the number of local variables allocated in the frame for this method (4 in this case). All local variables are referenced in the above instructions except the first one (at index 0), which holds the reference to the args argument. The other 3 local variables correspond to variables a, b and c in the source code.

The instructions from address 0 to 8 will do the following:

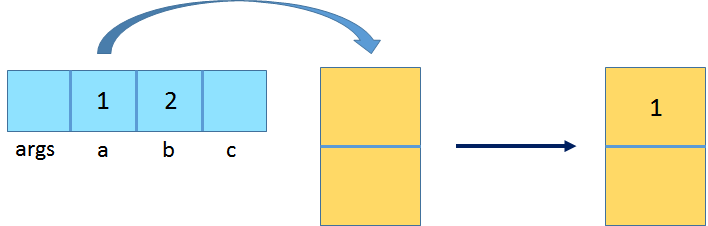

iconst_1: Push the integer constant 1 onto the operand stack.

![]()

istore_1: Pop the top operand (an int value) and store it in local variable at index 1, which corresponds to variable a.

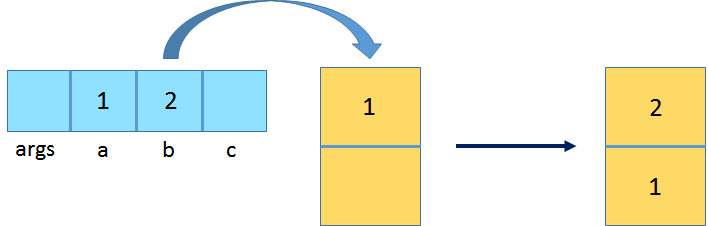

iconst_2: Push the integer constant 2 onto the operand stack.

![]()

istore_2: Pop the top operand int value and store it in local variable at index 2, which corresponds to variable b.

iload_1: Load the int value from local variable at index 1 and push it onto the operand stack.

iload_2: Load the int value from the local variable at index 1 and push it onto the operand stack.

iadd: Pop the top two int values from the operand stack, add them, and push the result back onto the operand stack.

istore_3: Pop the top operand int value and store it in local variable at index 3, which corresponds to variable c.

return: Return from the void method.

Each of the above instructions consists of only an opcode, which dictates exactly the operation to be executed by the JVM.

Method Invocations

In the above example, there is only one method, the main method. Let's assume that we need to a more elaborate computation for the value of variable c, and we decide to place that in a new method called calc:

public static void main(String[] args) {

int a = 1;

int b = 2;

int c = calc(a, b);

}

static int calc(int a, int b) {

return (int) Math.sqrt(Math.pow(a, 2) + Math.pow(b, 2));

}Let's see the resulting bytecode:

public static void main(java.lang.String[]);

descriptor: ([Ljava/lang/String;)V

flags: (0x0009) ACC_PUBLIC, ACC_STATIC

Code:

stack=2, locals=4, args_size=1

0: iconst_1

1: istore_1

2: iconst_2

3: istore_2

4: iload_1

5: iload_2

6: invokestatic #2 // Method calc:(II)I

9: istore_3

10: return

static int calc(int, int);

descriptor: (II)I

flags: (0x0008) ACC_STATIC

Code:

stack=6, locals=2, args_size=2

0: iload_0

1: i2d

2: ldc2_w #3 // double 2.0d

5: invokestatic #5 // Method java/lang/Math.pow:(DD)D

8: iload_1

9: i2d

10: ldc2_w #3 // double 2.0d

13: invokestatic #5 // Method java/lang/Math.pow:(DD)D

16: dadd

17: invokestatic #6 // Method java/lang/Math.sqrt:(D)D

20: d2i

21: ireturnThe only difference in the main method code is that instead of having the iadd instruction, we now an invokestatic instruction, which simply invokes the static method calc. The key thing to note is that the operand stack contained the two arguments that are passed to the method calc. In other words, the calling method prepares all arguments of the to-be-called method by pushing them onto the operand stack in the correct order. invokestatic (or a similar invoke instruction, as will be seen later) will subsequently pop these arguments, and a new frame is created for the invoked method where the arguments are placed in its local variable array.

We also notice that the invokestatic instruction occupies 3 bytes by looking at the address, which jumped from 6 to 9. This is because, unlike all instructions seen so far, invokestatic includes two additional bytes to construct the reference to the method to be invoked (in addition to the opcode). The reference is shown by javap as #2, which is a symbolic reference to the calc method, which is resolved from the constant pool described earlier.

The other new information is obviously the code for the calc method itself. It first loads the first integer argument onto the operand stack (iload_0). The next instruction, i2d, converts it to a double by applying widening conversion. The resulting double replaces the top of the operand stack.

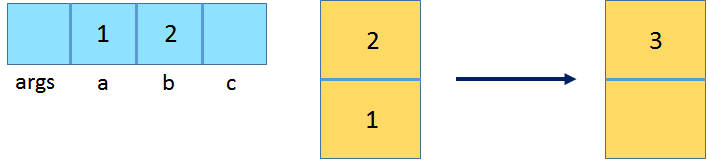

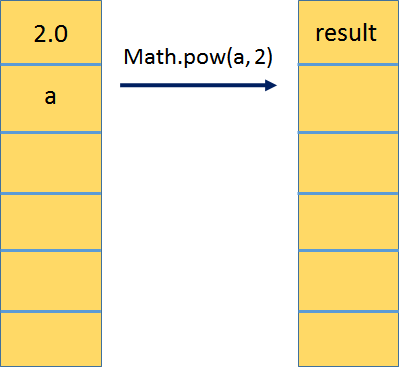

The next instruction pushes a double constant 2.0d (taken from the constant pool) onto the operand stack. Then the static Math.pow method is invoked with the two operand values prepared so far (the first argument to calc and the constant 2.0d). When the Math.pow method returns, its result will be stored on the operand stack of its invoker. This can be illustrated below.

The same procedure is applied to compute Math.pow(b, 2):

The next instruction, dadd, pops the top two intermediate results, adds them, and pushes the sum back to the top. Finally, invokestatic invokes Math.sqrt on the resulting sum, and the result is cast from double to int using narrowing conversion (d2i). The resulting int is returned to the main method, which stores it back to c (istore_3).

Instance Creations

Let's modify the example and introduce a class Point to encapsulate XY coordinates.

public class Test {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Point a = new Point(1, 1);

Point b = new Point(5, 3);

int c = a.area(b);

}

}

class Point {

int x, y;

Point(int x, int y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

public int area(Point b) {

int length = Math.abs(b.y - this.y);

int width = Math.abs(b.x - this.x);

return length * width;

}

}The compiled bytecode for the main method is shown below:

public static void main(java.lang.String[]);

descriptor: ([Ljava/lang/String;)V

flags: (0x0009) ACC_PUBLIC, ACC_STATIC

Code:

stack=4, locals=4, args_size=1

0: new #2 // class test/Point

3: dup

4: iconst_1

5: iconst_1

6: invokespecial #3 // Method test/Point."<init>":(II)V

9: astore_1

10: new #2 // class test/Point

13: dup

14: iconst_5

15: iconst_3

16: invokespecial #3 // Method test/Point."<init>":(II)V

19: astore_2

20: aload_1

21: aload_2

22: invokevirtual #4 // Method test/Point.area:(Ltest/Point;)I

25: istore_3

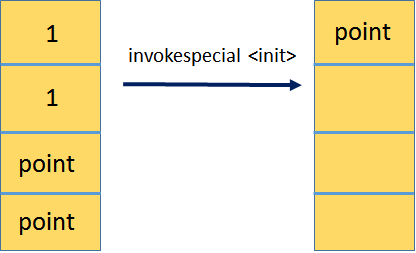

26: returnThe new instructions encountereted here are new , dup, and invokespecial. Similar to the new operator in the programming language, the new instruction creates an object of the type specified in the operand passed to it (which is a symbolic reference to the class Point). Memory for the object is allocated on the heap, and a reference to the object is pushed on the operand stack.

The dup instruction duplicates the top operand stack value, which means that now we have two references the Point object on the top of the stack. The next three instructions push the arguments of the constructor (used to initialize the object) onto the operand stack, and then invoke a special initialization method, which corresponds with the constructor. The next method is where the fields x and y will get initialized. After the method is finished, the top three operand stack values are consumed, and what remains is the original reference to the created object (which is, by now, successfully initialized).

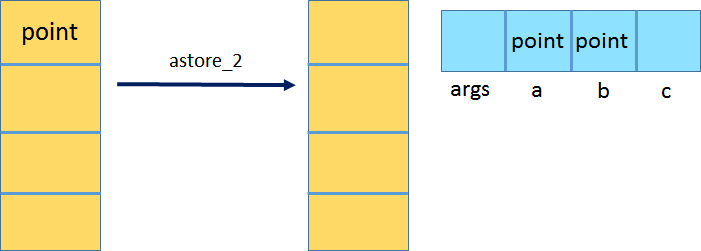

Next, astore_1 pops that Point reference and assigns it to the local variable at index 1 (the a in astore_1 indicates this is a reference value).

The same procedure is repeated for creating and initializing the second Point instance, which is assigned to variable b.

The last step loads the references to the two Point objects from local variables at indexes 1 and 2 (using aload_1 and aload_2 respectively), and invokes the area method using invokevirtual, which handles dispatching the call to the appropriate method based on the actual type of the object. For example, if the variable a contained an instance of type SpecialPoint that extends Point, and the subtype overrides the area method, then the overriden method is invoked. In this case, there is no subclass, and hence only one area method is available.

Note that even though the area method accepts one argument, there are two Point references on the top of the stack. The first one (pointA, which comes from variable a) is actually the instance on which the method is invoked (otherwise referred to as this in the programming language), and it will be passed in the first local variable of the new frame for the area method. The other operand value (pointB) is the argument to the area method.

The Other Way Around

You don't need to master the understanding of each instruction and the exact flow of execution to gain an idea about what the program does based on the bytecode at hand. For example, in my case, I wanted to check if the code employed a Java stream to read a file, and whether the stream was properly closed. Now given the following bytecode, it is relatively easy to determine that indeed a stream is used and most likely it is being closed as part of a try-with-resources statement.

public static void main(java.lang.String[]) throws java.lang.Exception;

descriptor: ([Ljava/lang/String;)V

flags: (0x0009) ACC_PUBLIC, ACC_STATIC

Code:

stack=2, locals=8, args_size=1

0: ldc #2 // class test/Test

2: ldc #3 // String input.txt

4: invokevirtual #4 // Method java/lang/Class.getResource:(Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/net/URL;

7: invokevirtual #5 // Method java/net/URL.toURI:()Ljava/net/URI;

10: invokestatic #6 // Method java/nio/file/Paths.get:(Ljava/net/URI;)Ljava/nio/file/Path;

13: astore_1

14: new #7 // class java/lang/StringBuilder

17: dup

18: invokespecial #8 // Method java/lang/StringBuilder."<init>":()V

21: astore_2

22: aload_1

23: invokestatic #9 // Method java/nio/file/Files.lines:(Ljava/nio/file/Path;)Ljava/util/stream/Stream;

26: astore_3

27: aconst_null

28: astore 4

30: aload_3

31: aload_2

32: invokedynamic #10, 0 // InvokeDynamic #0:accept:(Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;)Ljava/util/function/Consumer;

37: invokeinterface #11, 2 // InterfaceMethod java/util/stream/Stream.forEach:(Ljava/util/function/Consumer;)V

42: aload_3

43: ifnull 131

46: aload 4

48: ifnull 72

51: aload_3

52: invokeinterface #12, 1 // InterfaceMethod java/util/stream/Stream.close:()V

57: goto 131

60: astore 5

62: aload 4

64: aload 5

66: invokevirtual #14 // Method java/lang/Throwable.addSuppressed:(Ljava/lang/Throwable;)V

69: goto 131

72: aload_3

73: invokeinterface #12, 1 // InterfaceMethod java/util/stream/Stream.close:()V

78: goto 131

81: astore 5

83: aload 5

85: astore 4

87: aload 5

89: athrow

90: astore 6

92: aload_3

93: ifnull 128

96: aload 4

98: ifnull 122

101: aload_3

102: invokeinterface #12, 1 // InterfaceMethod java/util/stream/Stream.close:()V

107: goto 128

110: astore 7

112: aload 4

114: aload 7

116: invokevirtual #14 // Method java/lang/Throwable.addSuppressed:(Ljava/lang/Throwable;)V

119: goto 128

122: aload_3

123: invokeinterface #12, 1 // InterfaceMethod java/util/stream/Stream.close:()V

128: aload 6

130: athrow

131: getstatic #15 // Field java/lang/System.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

134: aload_2

135: invokevirtual #16 // Method java/lang/StringBuilder.toString:()Ljava/lang/String;

138: invokevirtual #17 // Method java/io/PrintStream.println:(Ljava/lang/String;)V

141: return

...We see occurrences of java/util/stream/Stream where forEach is called, preceded by a call to InvokeDynamic with a reference to a Consumer. And then we see a chunk of bytecode that calls Stream.close along with branches that call Throwable.addSuppressed. This is the basic code that gets generated by the compiler for a try-with-resources statement.

Here's the original source for completeness:

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Path path = Paths.get(Test.class.getResource("input.txt").toURI());

StringBuilder data = new StringBuilder();

try(Stream lines = Files.lines(path)) {

lines.forEach(line -> data.append(line).append("\n"));

}

System.out.println(data.toString());

}Conclusion

Thanks to the simplicity of the bytecode instruction set and the near absence of compiler optimizations when generating its instructions, disassembling class files could be one way to examine changes into your application code without having the source, if that ever becomes a need.

Published at DZone with permission of Mahmoud Anouti, DZone MVB. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments