Functional Test Coverage - taking BDD reporting to the next level

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeFrom an original article on Wakaleo.com

Conventional test reports, generated by tools such as JUnit or TestNG, naturally focus on what tests have been executed, and whether they passed or failed. While this is certainly useful from a testing perspective, these reports are far from telling the whole picture.

BDD reporting tools like Cucumber and JBehave take things a step further, introducing the concept of "pending" tests. A pending test is one that has been specified (for example, as an acceptance criteria for a user story), but which has not been implemented yet.

In BDD, we describe the expected behaviour of our application using concrete examples, that eventually form the basis of the "acceptance criteria" for the user stories we are implementing. BDD tools such as Cucumber and JBehave not only report on test results: they also report on the user stories that these tests validate.

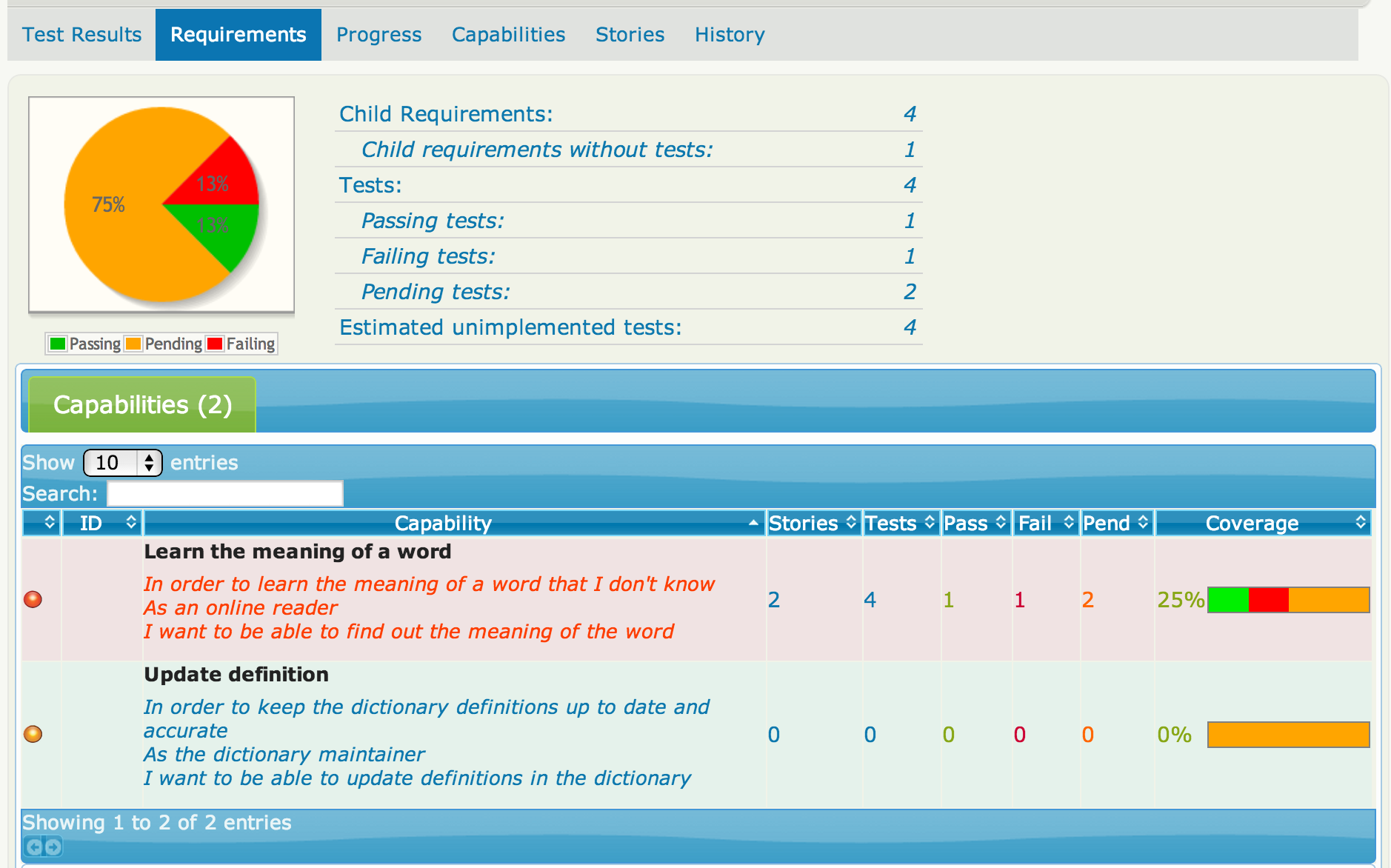

However this reporting is still limited for large projects, where the numbers of user stories can become unwieldy. User stories are not created in isolation: rather, user stories help describe features, which support capabilities that need to be implemented to achieve the business goals of the application. So it makes sense to be able to report on test results not only at the user story level, but also at higher levels, for example in terms of features and capabilities. This makes it easier to report on not only what stories have been implemented, but also what features and capabilities remain to be done. An example of such a report is shown in Figure 1 (or see the full report here).

Figure 1: A test coverage report listing both tested and untested requirements.

In agile projects, it is generally considered that a user story is not complete until all of its automated acceptance tests pass. Similarly, a feature cannot be considered ready to deliver until all of the acceptance criteria for the underlying user stories have been specified and implemented. However, sensible teams shy away from trying to define all of the acceptance criteria up-front, leaving this until the "last responsible moment", often shortly before the user story is scheduled to be implemented. For this reason, reports that relate project progress and status only in terms of test results are missing out on the big picture.

To get a more accurate idea of what features have been delivered, which ones are in progress, and what work remains to be done, we must think not in terms of test results, but in terms of the requirements as we currently understand them, matching the currently implemented tests to these requirements, but also pointing out what requirements currently have no acceptance criteria defined. And when graphs and reports illustrate how much progress has been made, the requirements with no acceptance criteria must also be part of the picture.

Requirements-level BDD reporting with Thucydides

Thucydides is an open source tool that puts some of these concepts into practice. Building on top of BDD tools such as JBehave, or using just ordinary JUnit tests, Thucydides reports not only on how the tests did, but also fits them into the broader picture, showing what requirements have been tested and, just as importantly, what requirements haven't. You can learn more about Thucydides in this tutorial or on the Thucydides website.

During the rest of this article, we will see how to report on both your requirements and your test results using Thucydides, using a very simple directory-based approach. You can follow along with this example by cloning the Github project at https://github.com/thucydides-webtests/thucydides-simple-demo

Simple requirements in Thucydides - a directory-based approach

Thucydides can integrate with many different requirement management systems, and it is easy to write your own plugin to tailor the integration to suite your particular environment. A popular approach, for example, is to store requirements in JIRA and to use Thucydides to read the requirements hierarcy directly from the JIRA cards. However the simplest approach, which uses a directory-based approach, is probably the easiest to use to get started, and it is that approach that we will be looking at here.

Requirements can usually be organized in a hierarchial structure. By default, Thucydides uses a three-level hierarchy of requirements. At the top level, capabilities represent a high-level capacity that the application must provide to meet the application's business goals. At the next level down, features help deliver these capabilities. To make implementation easier, a feature can be broken up into user stories, each of which in turn can contain a number of acceptance criteria.

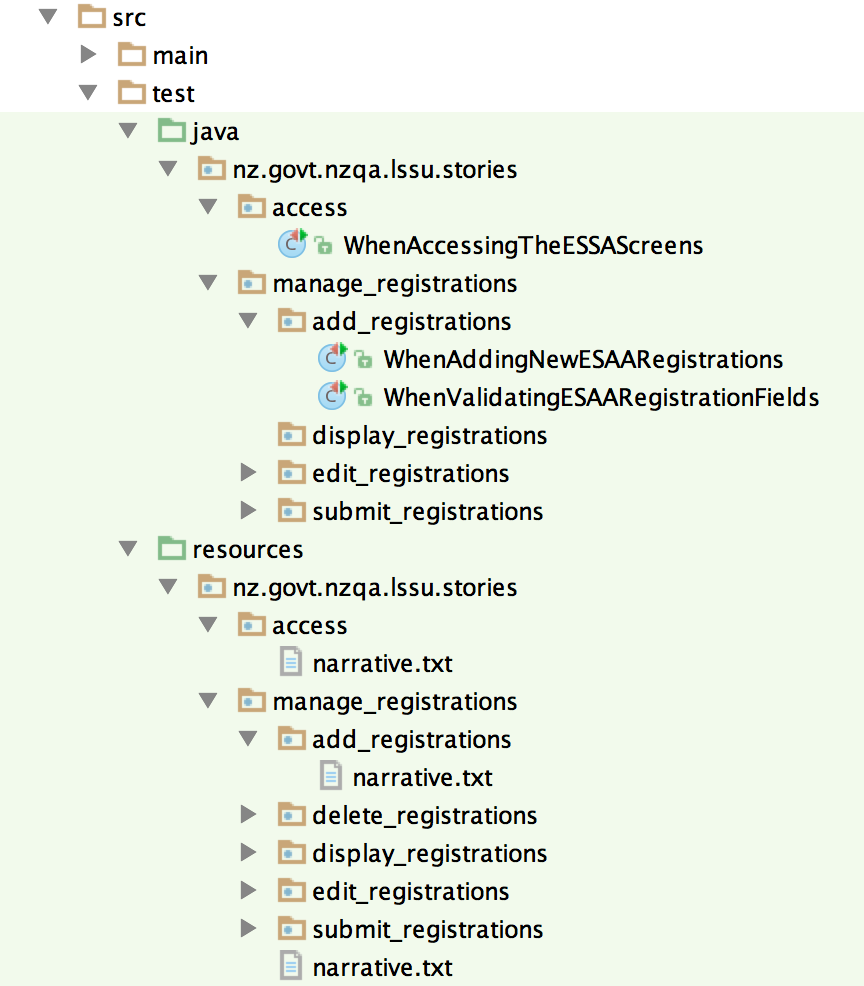

Figure 2: JUnit test directories mirror the requirements hierarchy.

Of course, you don't have to use this structure if it doesn't suit you. You can override the thucydides.capability.types system property to provide your own hierarchy. For example, if you wanted a hierarchy with modules,epics, and features, you would just set thucydides.capability.types to "module,epic,feature".

When we use the default directory-based requirements strategy in Thucydides, the requirements are stored in a hierarchial directory structure that matches the requirements hierarchy. At the lowest level, a user story is represented by a JBehave *.story file, an easyb story, or a JUnit test. All of the other requirements are represented as directories (see Figure 2 for an example of such a structure).

In each requirements directory, you can optionally place a file called narrative.txt, which contains a free-text summary of the requirement. This will appear in the reports, with the first line appearing as the requirement title. A typical narrative text is illustrated in the following example:

Learn the meaning of a word In order to learn the meaning of a word that I don't know As an online reader I want to be able to find out the meaning of the word

If you are implementing the acceptance criteria as JUnit tests, just place the JUnit tests in the package that matches the correspoinding requirement. You need to use the thucydides.test.root system property to specify the root package of your requirements. For the example in Figure 2, this value should be set to nz.govt.nzqa.lssu.stories.

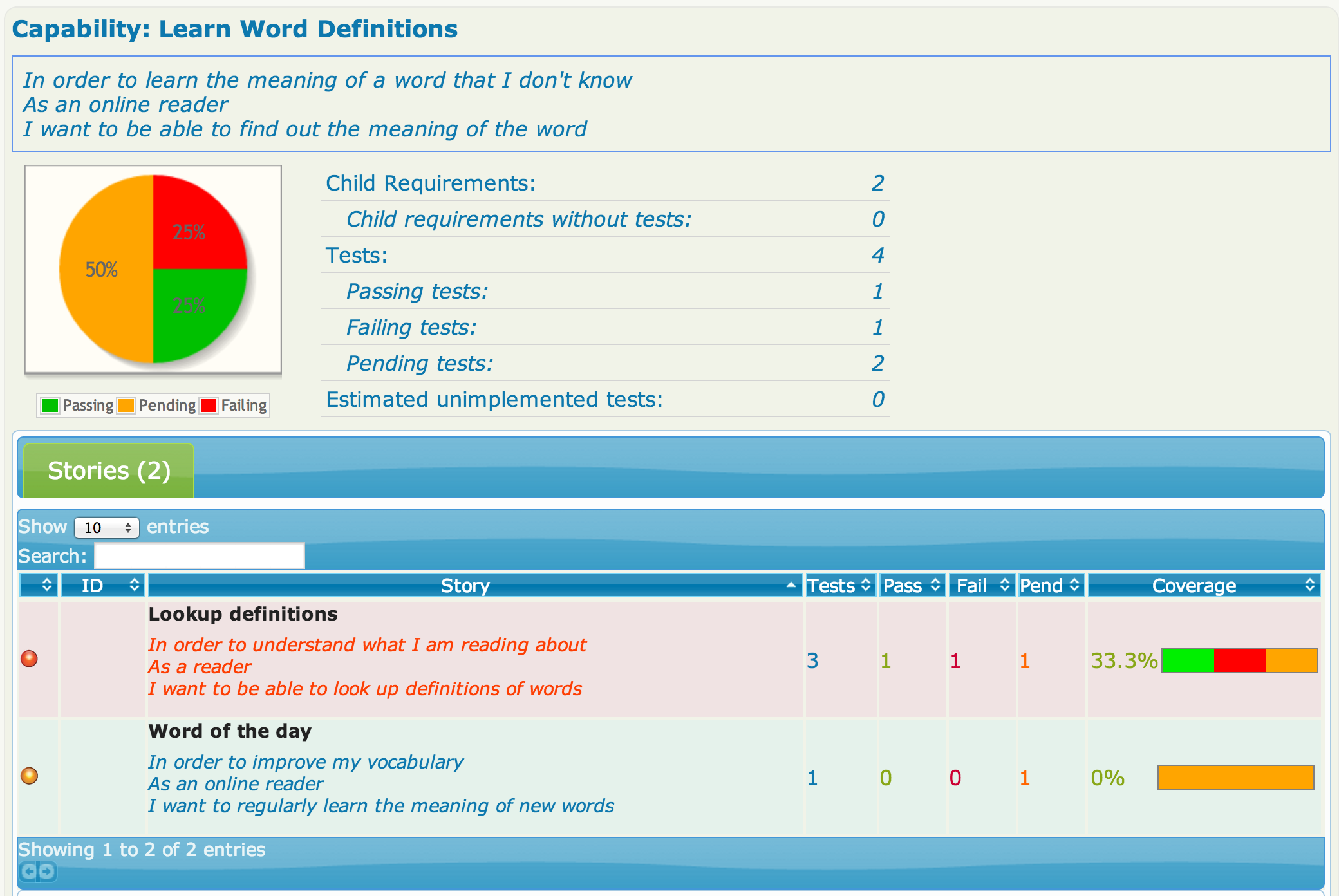

Figure 3: The narrative.txt file appears in the reports to describe a requirement.

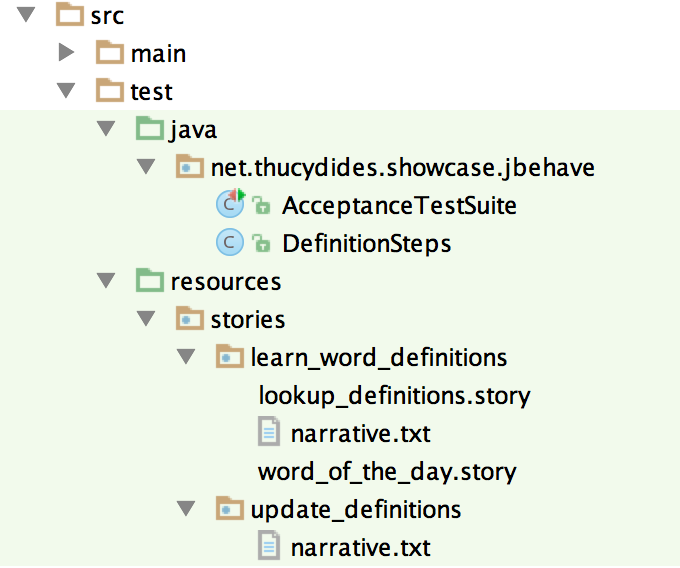

If you are using JBehave, just place the *.story files in the src/test/resources/stories directory, again respecting a directory structure that corresponds to your requirement hierarchy. The narrative.txt files also work for JBehave requirements.

Progress is measured by the total number of passing, failing or pending acceptance criteria, either for the whole project (at the top level), or within a particular requirement as you drill down the requirements hierarchy. For the purposes of reporting, a requirement with no acceptance criteria is attributed an arbitrary number of "imaginary" pending acceptance criteria. Thucydides considers that you need 4 tests per requirement by default, but you can override this value using the thucydides.estimated.tests.per.requirement system property.

Figure 3: For JBehave, everything goes under src/test/resources/stories.

Conclusion

BDD is an excellent approach for communicating with, and reporting back to, stakeholders. However, for accurate acceptance test reporting on real-world projects, you need to go beyond the story level, and cater for the whole requirements hierarchy. In particular, you need to not only report on tests that have been executed, but also allow for the tests that haven't been written yet.

Thucydides puts these concepts into practice: using a simple directory-based convention, you can easily integrate your requirements hierarcy into your acceptance tests.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments