Choosing a Microservices Deployment Strategy Part 6

Here's part 6 of our microservices architecture, with a focus on deployment strategy!

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeThis is the sixth article in a series about building applications with microservices. The first article introduces the Microservice Architecture pattern and discusses the benefits and drawbacks of using microservices. The following articles discuss different aspects of the microservice architecture: using an API Gateway, inter-process communication, service discovery, and event-driven data management. In this article, we look at strategies for deploying microservices.

[Editor’s note — The other articles currently available in this seven-part series are:

- Introduction to Microservices

- Building Microservices: Using an API Gateway

- Building Microservices: Inter-Process Communication in a Microservices Architecture

- Service Discovery in a Microservices Architecture

- Event-Driven Data Management for Microservices ]

Motivations

Deploying a monolithic application means running multiple, identical copies of a single, usually large application. You typically provision N servers (physical or virtual) and run M instances of the application on each one. The deployment of a monolithic application is not always entirely straightforward, but it is much simpler than deploying a microservices application.

A microservices application consists of tens or even hundreds of services. Services are written in a variety of languages and frameworks. Each one is a mini-application with its own specific deployment, resource, scaling, and monitoring requirements. For example, you need to run a certain number of instances of each service based on the demand for that service. Also, each service instance must be provided with the appropriate CPU, memory, and I/O resources. What is even more challenging is that despite this complexity, deploying services must be fast, reliable and cost-effective.

There are a few different microservice deployment patterns. Let’s look first at the Multiple Service Instances per Host pattern.

Multiple Service Instances per Host Pattern

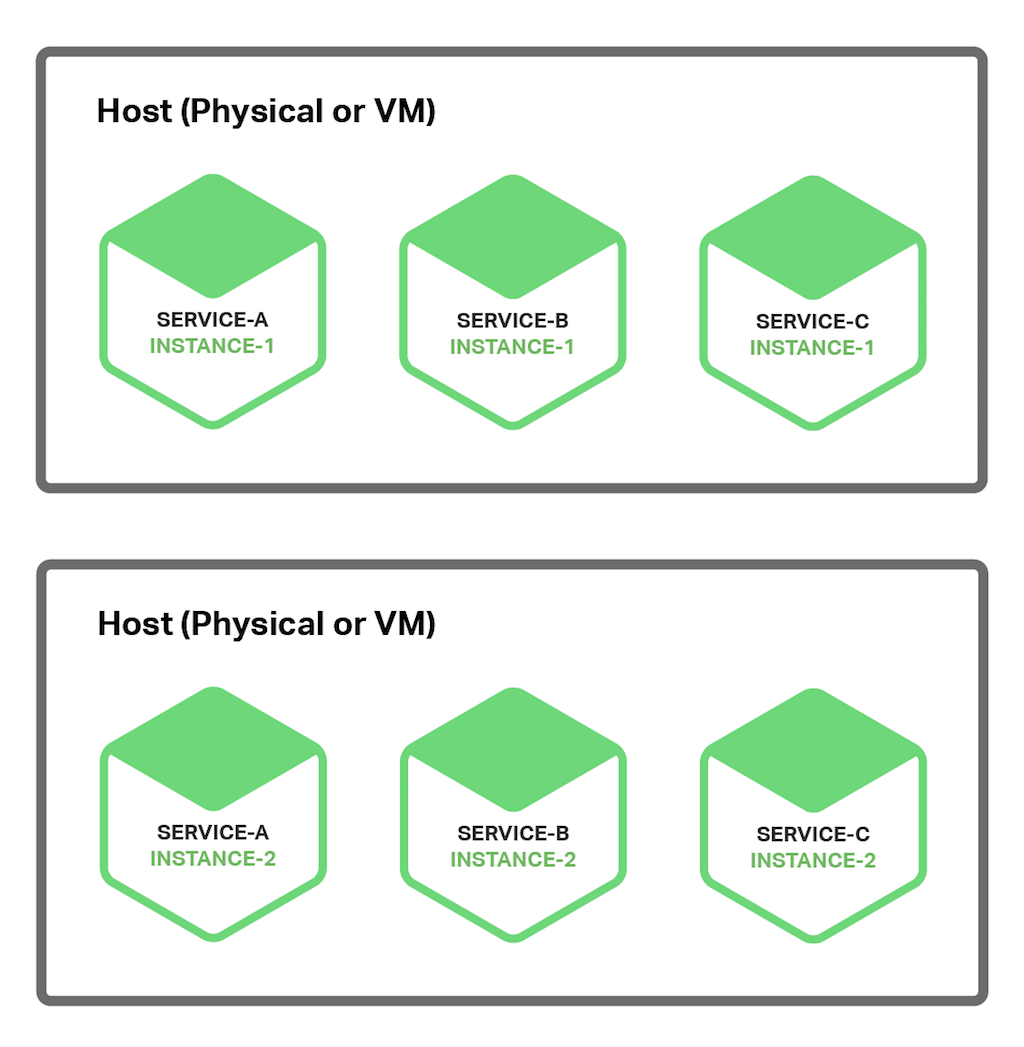

One way to deploy your microservices is to use the Multiple Service Instances per Host pattern. When using this pattern, you provision one or more physical or virtual hosts and run multiple service instances on each one. In many ways, this the traditional approach to application deployment. Each service instance runs on a well-known port on one or more hosts. The host machines are commonly treated like pets.

The following diagram shows the structure of this pattern.

There are a couple of variants of this pattern. One variant is for each service instance to be a process or a process group. For example, you might deploy a Java service instance as a web application on an Apache Tomcat server. A Node.js service instance might consist of a parent process and one or more child processes.

The other variant of this pattern is to run multiple service instances in the same process or process group. For example, you could deploy multiple Java web applications on the same Apache Tomcat server or run multiple OSGI bundles in the same OSGI container.

The Multiple Service Instances per Host pattern has both benefits and drawbacks. One major benefit is its resource usage is relatively efficient. Multiple service instances share the server and its operating system. It is even more efficient if a process or process group runs multiple service instances, for example, multiple web applications sharing the same Apache Tomcat server and JVM.

Another benefit of this pattern is that deploying a service instance is relatively fast. You simply copy the service to a host and start it. If the service is written in Java, you copy a JAR or WAR file. For other languages, such as Node.js or Ruby, you copy the source code. In either case, the number of bytes copied over the network is relatively small.

Also, because of the lack of overhead, starting a service is usually very fast. If the service is its own process, you simply start it. Otherwise, if the service is one of several instances running in the same container process or process group, you either dynamically deploy it into the container or restart the container.

Despite its appeal, the Multiple Service Instances per Host pattern has some significant drawbacks. One major drawback is that there is little or no isolation of the service instances unless each service instance is a separate process. While you can accurately monitor each service instance’s resource utilization, you cannot limit the resources each instance uses. It’s possible for a misbehaving service instance to consume all of the memory or CPU of the host.

There is no isolation at all if multiple service instances run in the same process. All instances might, for example, share the same JVM heap. A misbehaving service instance could easily break the other services running in the same process. Moreover, you have no way to monitor the resources used by each service instance.

Another significant problem with this approach is that the operations team that deploys a service has to know the specific details of how to do it. Services can be written in a variety of languages and frameworks, so there are lots of details that the development team must share with operations. This complexity increases the risk of errors during deployment.

As you can see, despite its familiarity, the Multiple Service Instances per Host pattern has some significant drawbacks. Let’s now look at other ways of deploying microservices that avoid these problems.

Service Instance per Host Pattern

Another way to deploy your microservices is the Service Instance per Host pattern. When you use this pattern, you run each service instance in isolation on its own host. There are two different specializations of this pattern: Service Instance per Virtual Machine and Service Instance per Container.

Service Instance per Virtual Machine Pattern

When you use Service Instance per Virtual Machine pattern, you package each service as a virtual machine (VM) image such as an Amazon EC2 AMI. Each service instance is a VM (for example, an EC2 instance) that is launched using that VM image. The following diagram shows the structure of this pattern:

This is the primary approach used by Netflix to deploy its video streaming service. Netflix packages each of its services as an EC2 AMI using Aminator. Each running service instance is an EC2 instance.

There are a variety tools that you can use to build your own VMs. You can configure your continuous integration (CI) server (for example, Jenkins) to invoke Aminator to package your services as an EC2 AMI. Packer.io is another option for automated VM image creation. Unlike Animator, it supports a variety of virtualization technologies including EC2, DigitalOcean, VirtualBox, and VMware.

The company Boxfuse has a compelling way to build VM images, which overcomes the drawbacks of VMs that I describe below. Boxfuse packages your Java application as a minimal VM image. These images are fast to build, boot quickly, and are more secure since they expose a limited attack surface.

The company CloudNative has the Bakery, a SaaS offering for creating EC2 AMIs. You can configure your CI server to invoke the Bakery after the tests for your microservice pass. The Bakery then packages your service as an AMI. Using a SaaS offering such as the Bakery means that you don’t have to waste valuable time setting up the AMI creation infrastructure.

The Service Instance per Virtual Machine pattern has a number of benefits. A major benefit of VMs is that each service instance runs in complete isolation. It has a fixed amount of CPU and memory and can’t steal resources from other services.

Another benefit of deploying your microservices as VMs is that you can leverage mature cloud infrastructure. Clouds such as AWS provide useful features such as load balancing and autoscaling.

Another great benefit of deploying your service as a VM is that it encapsulates your service’s implementation technology. Once a service has been packaged as a VM it becomes a black box. The VM’s management API becomes the API for deploying the service. Deployment becomes much simpler and more reliable.

The Service Instance per Virtual Machine pattern has some drawbacks, however. One drawback is less efficient resource utilization. Each service instance has the overhead of an entire VM, including the operating system. Moreover, in a typical public IaaS, VMs come in fixed sizes and it is possible that the VM will be underutilized.

Moveover, a public IaaS typically charges for VMs regardless of whether they are busy or idle. An IaaS such as AWS provides autoscaling but it is difficult to react quickly to changes in demand. Consequently, you often have to over-provision VMs, which increases the cost of deployment.

Another downside of this approach is that deploying a new version of a service is usually slow. VM images are typically slow to build due to their size. Also, VMs are typically slow to instantiate, again because of their size. Also, an operating system typically takes some time to start up. Note, however, that this is not universally true, since lightweight VMs such as those built by Boxfuse exist.

Another drawback of the Service Instance per Virtual Machine pattern is that usually, you (or someone else in your organization) is responsible for a lot of undifferentiated heavy lifting. Unless you use a tool such as Boxfuse that handles the overhead of building and managing the VMs, then it is your responsibility. This necessary but time-consuming activity distracts from your core business.

Let’s now look at an alternative way to deploy microservices that are more lightweight yet still has many of the benefits of VMs.

Service Instance per Container Pattern

When you use the Service Instance per Container pattern, each service instance runs in its own container. Containers are a virtualization mechanism at the operating system level. A container consists of one or more processes running in a sandbox. From the perspective of the processes, they have their own port namespace and root filesystem. You can limit a container’s memory and CPU resources. Some container implementations also have I/O rate limiting. Examples of container technologies include Docker and Solaris Zones.

The following diagrams shows the structure of this pattern:

To use this pattern, you package your service as a container image. A container image is a filesystem image consisting of the applications and libraries required to run the service. Some container images consist of a complete Linux root filesystem. Others are more lightweight. To deploy a Java service, for example, you build a container image containing the Java runtime, perhaps an Apache Tomcat server, and your compiled Java application.

Once you have packaged your service as a container image, you then launch one or more containers. You usually run multiple containers on each physical or virtual host. You might use a cluster manager such as Kubernetes or Marathon to manage your containers. A cluster manager treats the hosts as a pool of resources. It decides where to place each container based on the resources required by the container and resources available on each host.

The Service Instance per Container pattern has both benefits and drawbacks. The benefits of containers are similar to those of VMs. They isolate your service instances from each other. You can easily monitor the resources consumed by each container. Also, like VMs, containers encapsulate the technology used to implement your services. The container management API also serves as the API for managing your services.

However, unlike VMs, containers are a lightweight technology. Container images are typically very fast to build. For example, on my laptop, it takes as little as 5 seconds to package a Spring Boot application as a Docker container. Containers also start very quickly since there is no lengthy OS boot mechanism. When a container starts, what runs is the service.

There are some drawbacks to using containers. While container infrastructure is rapidly maturing, it is not as mature as the infrastructure for VMs. Also, containers are not as secure as VMs since the containers share the kernel of the host OS with one another.

Another drawback of containers is that you are responsible for the undifferentiated heavy lifting of administering the container images. Also, unless you are using a hosted container solution such as Google Container Engine or Amazon EC2 Container Service (ECS), then you must administer the container infrastructure and possibly the VM infrastructure that it runs on.

Also, containers are often deployed on an infrastructure that has per-VM pricing. Consequently, as described earlier, you will likely incur the extra cost of over-provisioning VMs in order to handle spikes in load.

Interestingly, the distinction between containers and VMs is likely to blur. As mentioned earlier, Boxfuse VMs are fast to build and start. The Clear Containers project aims to create lightweight VMs. There is also growing interest in unikernels. Docker, Inc recently acquired Unikernel Systems.

There is also the newer and increasingly popular concept of server-less deployment, which is an approach that sidesteps the issue of having to choose between deploying services in containers or VMs. Let’s look at that next.

Serverless Deployment

AWS Lambda is an example of serverless deployment technology. It supports Java, Node.js, and Python services. To deploy a microservice, you package it as a ZIP file and upload it to AWS Lambda. You also supply metadata, which among other things specifies the name of the function that is invoked to handle a request (a.k.a. an event). AWS Lambda automatically runs enough instances of your microservice to handle requests. You are simply billed for each request based on the time taken and the memory consumed. Of course, the devil is in the details and you will see shortly that AWS Lambda has limitations. But the notion that neither you as a developer nor anyone in your organization need worry about any aspect of servers, virtual machines, or containers is incredibly appealing.

A Lambda function is a stateless service. It typically handles requests by invoking AWS services. For example, a Lambda function that is invoked when an image is uploaded to an S3 bucket could insert an item into a DynamoDB images table and publish a message to a Kinesis stream to trigger image processing. A Lambda function can also invoke third-party web services.

There are four ways to invoke a Lambda function:

- Directly, using a web service request

- Automatically, in response to an event generated by an AWS service such as S3, DynamoDB, Kinesis, or Simple Email Service

- Automatically, via an AWS API Gateway to handle HTTP requests from clients of the application

- Periodically, according to a

cron-like schedule

As you can see, AWS Lambda is a convenient way to deploy microservices. The request-based pricing means that you only pay for the work that your services actually perform. Also, because you are not responsible for the IT infrastructure you can focus on developing your application.

There are, however, some significant limitations. It is not intended to be used to deploy long-running services, such as a service that consumes messages from a third-party message broker. Requests must complete within 300 seconds. Services must be stateless since in theory AWS Lambda might run a separate instance for each request. They must be written in one of the supported languages. Services must also start quickly; otherwise, they might be timed out and terminated.

Summary

Deploying a microservices application is challenging. There are tens or even hundreds of services written in a variety of languages and frameworks. Each one is a mini-application with its own specific deployment, resource, scaling, and monitoring requirements. There are several microservice deployment patterns including Service Instance per Virtual Machine and Service Instance per Container. Another intriguing option for deploying microservices is AWS Lambda, a serverless approach. In the next and final part of this series, we will look at how to migrate a monolithic application to a microservice architecture.

[Editor’s note — The other articles currently available in this seven-part series are:

- Introduction to Microservices

- Building Microservices: Using an API Gateway

- Building Microservices: Inter-Process Communication in a Microservices Architecture

- Service Discovery in a Microservices Architecture

- Event-Driven Data Management for Microservices ]

Thsi article was written by guest blogger Chris Richardson. He is the founder of the original CloudFoundry.com, an early Java PaaS (Platform as a Service) for Amazon EC2. He now consults with organizations to improve how they develop and deploy applications. He also blogs regularly about microservices at http://microservices.io.

Published at DZone with permission of Chris Richardson. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments