Agile Git Branching Strategies in 2023

This article describes different branching strategies and presents a comparative analysis of Git-Flow, GitHub-Flow, and trunk-based development approaches.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeI have experience working on many projects, and I have found that the right choice for a branching strategy is essential for project success. In this article, I’ll describe different branching strategies. Nowadays, Git-Flow is very popular and well-documented. However, there are a few other alternatives like GitHub-Flow and the Trunk-based approach that exist, and some teams tend to move away from git-flow, and this article will describe why some other branching models may work better for your and your team.

Why Do We Need Git?

The reason why we have to use a (distributed) version control system like Git, and another, seems very obvious since it is used in almost every project, and having (D)VCS seems a standard nowadays. However, the question is why it is so. The answer is we are using version control because, as a team, we want to collaborate our effort to work on the same product and the same goal, and with the use of (distributed) version control systems like Git, we can integrate our individual contributions into a single product.

Since I’ve mentioned the integration of individual contribution, it is worth stating here that a version control system is an essential part of Continuous Integration or commonly known as CI. And the right branch strategy choice should support the CI process and our collaborative efforts to integrate the individual contributions of teammates into a single product, as mentioned before.

Git Branching: Use Cases

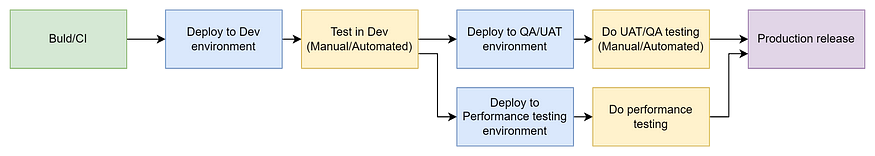

In terms of code versioning and branching — a continuous delivery pipeline adds certain challenges to maintaining a couple of different versions of the product at the same time. And considering that that testing and release approval take time, it is quite often the team tends to move ahead with the development of new features for the next releases, while the current release requires maintenance and support.

For the challenges that come together with the project delivery pipeline, we need efficient tooling to maintain the efficient process and support different versions of our application in different stages — and this is where git branches are coming into play.

My assumption is that you are already familiar with Git basics, such as the terms: branch, commit, master, sha, merge, diff, and change. So, the emphasis is mainly to understand how git branches can be efficiently maintained.

Before going into a comparison of different branching strategies, let’s formalize first a little few requirements which are typically needed for a project:

UC 1: Individual Contribution

- UC 1.1 — Local copy

- UC 1.2 — Prototyping

Let’s start from the basics here — VCS and CI are usually considered tools for team collaboration, and typical development is done by individuals (or pair) who have a copy of the code, known as a working copy, on a computer where any part of that copy can be changed. Working copy enables any sort of prototyping and experiments with the local copy. And being able to execute and debug applications from the working copy is an essential part of the CI process.

About the meaning of working copy, you can read more here.

UC 2: History

- UC 2.1 — Backup

- UC 2.2 — Rollback

- UC 2.3 — Difference

- UC 2.4 — git-blame

Also, prototyping on a local working copy means that it is easy to mess up anything in the local environment, and there should be a way to restore from some sort of backup. With Git you can easily navigate through the history, revert some changes, and do the diff comparison between any of two versions of the code like your local copy and production, or production and a release candidate, or any other two versions. And being able to navigate through history do able to do any kind of comparison is essential for troubleshooting.

It is also worth noting that CI also suggested the revert branch used for CI in certain scenarios when the build is broken to enable further development and resolved blocker so another developer can commit their changes to the CI branch.

Also, history greatly helps to troubleshoot — if there is some unfamiliar code with history, you can track it back to the author and provide some documentation with reasoning to under code flows.

UC 3: Team Collaboration

UC 3.1 — Continuous Integration

As I mentioned before, the team is built of individual contributors — while each contributor builds something in parallel, and at some point, it is important to integrate the efforts, it is worth stating the importance of the Continuous Integration process again.

The challenges that come here are while you building your code and someone doing something in parallel, some parallel versions will become incompatible. In most simple scenarios, it could be solved through the git merge conflict resolution process; however, it will not address logical incompatibilities.

And for that reason, CI practice suggests integrating changes often. About once a day or so.

There exists certain criticism about long-lived feature branches as something that should be avoided. Even if we tested something quite well in a local copy(feature branch), it doesn’t mean that everything will work well after integration — so it is recommended to do continuous integration as often as possible.

In my experience with projects where code review is done, merging to the CI branch once a day is not achievable. However, still, the feature branch should not live too long.

UC 4: Code Review, Quality Gates

- UC 4.1 — Review code before integrating

- UC 4.2 — Testing before CI build is broker on the mainline branch

The code review process nowadays is required for most of the team, and typically, code review is required before anything is merged.

UC 5: Release Candidates

- UC 5.1 — Developing new features

- UC 5.2 — Testing release candidates

The challenge that comes with the release candidate is, quite often, teams can have three different versions of software: Something already running in production, while the team started working on a new functionality set, and the set of functionality is different from that is being tested for currently upcoming production release.

And the challenge here is that testing of release candidates can take a long time. Meanwhile, the team should have the flexibility to contribute and develop new functionality in parallel that most likely will not be included in the current upcoming release.

UC 6: Production Maintenance

- UC 6.1 — Production hotfixes

Production issues typically happen suddenly and unexpectedly while there is a release candidate in the last stage of testing, which still can take a long time to test, and for such a situation, business and management might require to deploy a hotfix before the release candidate, and there should be a shortcut to release and deploy hotfix without releasing entire release candidate.

UC 7: Alignment With Scrum/Agile

- UC 7.1 — Frequent internal releases every iteration

- UC 7.2 — Production release planning of multiple iterations

The iterative development using Scrum requires that every sprint team should deliver a well-tested functionality kind of internal release; however, it is not necessary that the team should do the production release — and from the branching strategy perspective, it is actually required to make it flexible, so deployment/testing of iteration deliverable could be done in parallel to currently upcoming production release.

The efficient branching strategy should be flexible for businesses and management to decide how many iterations and functionalities to be completed before the system is released to production. And considering that each iteration will have well-tested deliverables, it should be possible to go into production anytime.

Git-Flow Branching Strategy

Git-Flow is a very well-known branching strategy. It has been on the market for ten years, and it is very flexible and can address all the use cases described above. However, there is certain criticism around that strategy.

The initial idea was described by Vincent Driessen and also popularized by Atlassian.

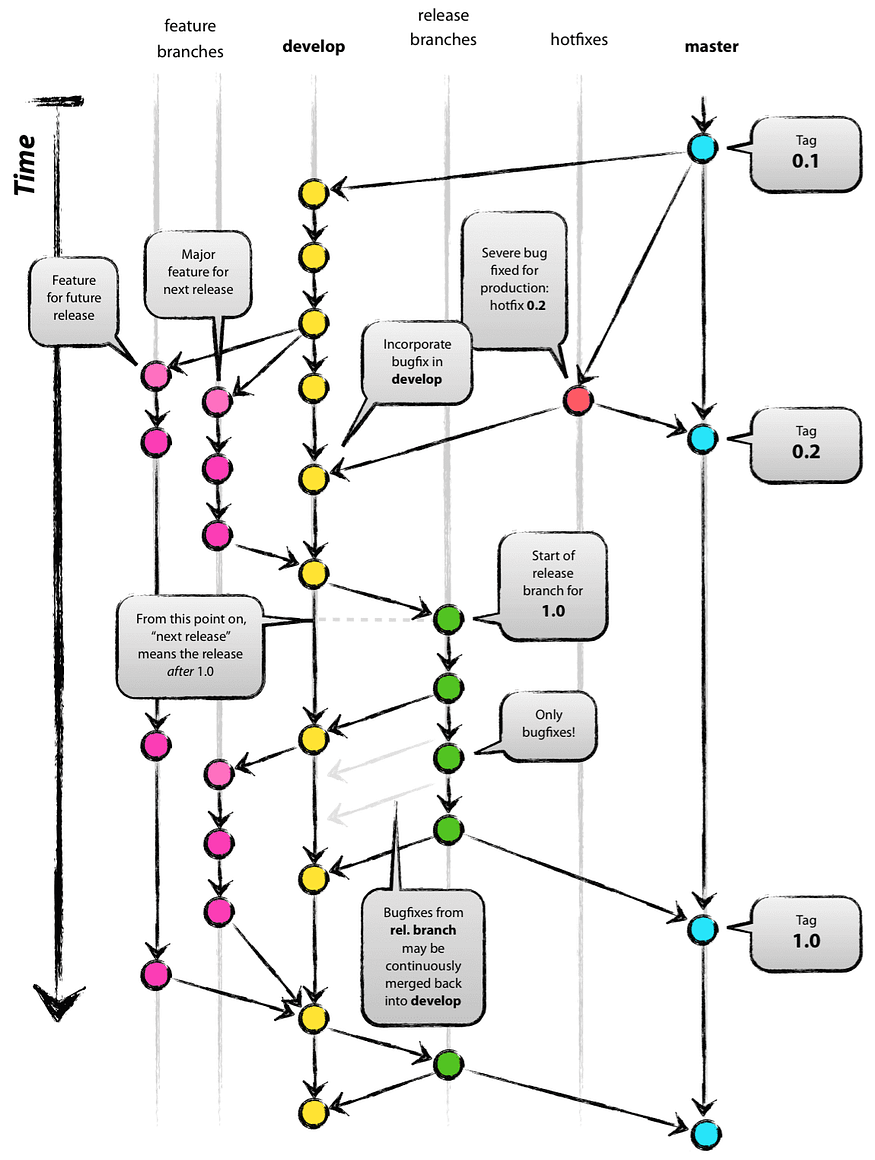

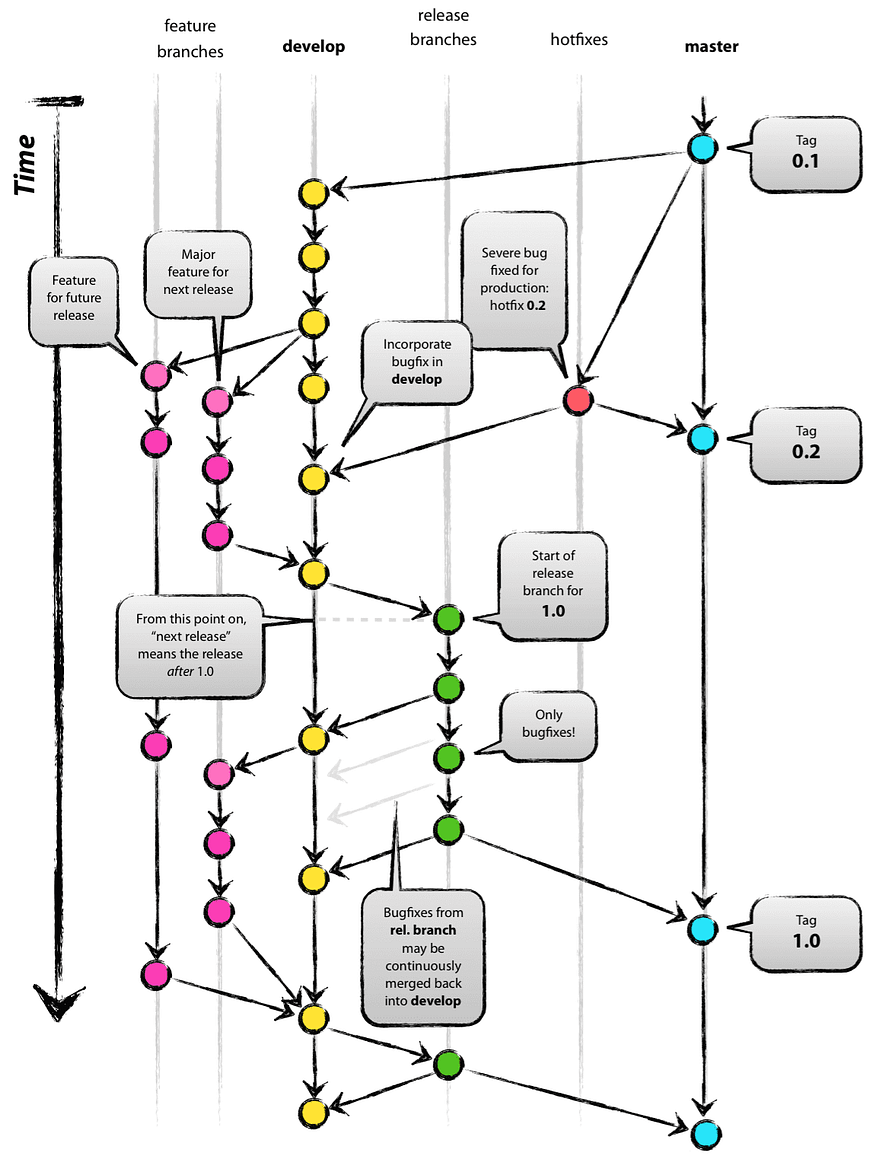

The main idea behind Git-Flow is to introduce a new development branch that is used by the team mainly for CI to integrate their changes with new functionality, while stable versions released into production are kept in the master(main) branch. The flexibility of Git-Flow is done mainly through kind of cherry-picking the usage of features and hotfix branches. It is not actually exactly Git cherry-picking because cherry-picking in Git terminology is the copying of a commit from one branch to another, and real cherry-picking tends to lose the Git history and complicates the Git merge conflict resolution process. Here with Git-Flow, we actually have to merge our feature/hotfix branch, so all the history will be preserved, which is important for use case UC2.

Let’s go by uses case one by one and see how it fits development demands.

UC 1: The typical development start from slicing a branch for feature development or hotfix. The main difference between development and hotfix — is that hotfix is done against the released production version (UC6), so the production tag version is used to slice a hotfix branch, while feature development is done again the CI branch (UC 5) and the feature branch is sliced from develop branch.

Let’s say we need to make a hotfix. First, we need to create a hotfix branch from the production tag version:

git checkout main

git checkout -b hotfix_branch

It usually recommends that two developers shouldn’t check in their changes into the same hotfix/feature branch, so the branch is mainly used for individual development(UC1) until the moment it will be integrated with a mainline branch like develop or master(main) (UC 3).

UC 2, UC 3: The history is important here since we sliced a branch, and the branch will inherit all the history of the original branch, whether it is the master(main) or developed branch. Once the development of the hotfix/feature is done, it needs to be merged back into a mainline branch like develop or master(main) branch.

- Hotfix is merged into both branches: develop and master(main).

- Feature merged only in develop branch.

This is an example of command how to merge a hotfix branch:

git checkout main

git merge hotfix_branch

git checkout develop

git merge hotfix_branch

git branch -D hotfix_branch

As you can see, since we merged it back, all the hotfix history will be shared with the master and develop branches (UC 2). Also, once this operation is done, the changes are coming through a continuous integration process with the team (UC 3)

UC 4 Since all individual development work is done either in the feature or hotfix branch, the team can push that branch through the quality process like code review, CI quality gates, whatever.

Code review and merge approval typically take time for the reviewer to read the code and communicate. The owner of the feature branch can actually work in parallel at this moment on multiple things in multiple parallel feature branches.

UC 5, UC 6: because there is 3 different type of branches develop, master(main) and feature/hotfix team can work in parallel on multiple things:

- Develop with feature branches— Do necessary changes for the release candidate in order to prepare the production release

- Master(main) with hotfix branch — Do the production maintenance to release changes scoped to hotfix only

- Feature branch — Technically, you can start working on a new feature branch that is not planned for the current upcoming release. Just keep developing here without reintegrating back into develop branch. The careful reader may notice here that it is against the CI process best practice. However, criticism of Git-Flow will be later.

UC 7: Alignment with SDLC is very important here, and the fact that develop and master(main) branches are separated, the scrum team can do as many internal releases as needed and be ready for production release at any time from the develop branch.

Git-Flow Criticism

Git-Flow is something known for the last decade and is still a very popular approach, and as you can see above, it can address all production needs. However, the question is why some organization with complex development process tends to move away from git-flow.

For example, Vincent Driessen, who initially invented Git-Flow, also recommends moving away to something more modern like GitHub-Flow.

Atlassian nowadays considers Git-Flow as a legacy branching model — their suggestion is to move to a trunk-based approach.

Martin Fowler, a known engineer and author of best sellers of enterprise development patterns, criticized git flow for long-living feature branching that disrupts the CI process, and that criticism is quite reasonable:

With git-flow, there is a certain fundamental issue. Let’s go through them:

Develop and Master (Main) Branch Divergence

The first thing that you can notice in the diagram above is that the master commits that are supposed to be most stable and running in production are actually never tested in a local development working copy environment, where all the development is happening in the first place, and it violates CI process since to the moment it is merged into the master branch. And it is quite easy that a newly developed, well-tested in develop branch will never work once it is merged into the master branch, for the reason described above.

Also, looking at the diagram above, it seems like a master (main) branch is a write-only branch, where the developer pushes changes but never reads from there until the moment the problem is already happening. In this case, the process requires slicing a hotfix is created, and there is a chance that a portion of the master branch will be merged back into develop branch kind of CI branch. However, the Git merge process is quite a sophisticated thing, and it will not pull the master branch entirely into development essential if some Git conflicts were resolved in the past.

Eventually, due to the Git merge conflicts resolution process, the divergence between hotfix, develop, and master(main) branches will appear, and it will impact further development.

Long-Living Feature Branches

There are no particular Git-Flow guidelines regarding the length of the feature branches. However, git-flow encourages developers to do the work in feature branches. Actually, if the team can do Git-Flow with short-living feature branches, it is not really an issue; however, since there are no strict guidelines, long-living feature branch happens quite often with Git-Flow.

Git History Cumbersomeness

The fact is that linear history is much easier to navigate than history built of many relations between merge commits and in many teams. I was working with a team where Git squash commits for pull requests were quite often encouraged, and history was much cleaner and easier to understand. With Git-Flow, it is not really possible to build linear history since there are two independent branches, and things are branch cherry-picking between them, which is obviously seen in the diagram above.

Speaking about Git history complexity, and actually, if you take a look again diagram with Git-Flow, that history looks very logical; however, Git history doesn’t work the way it is drawn in the picture, and the particular Git commit doesn’t actually belong to the branch, it exists only in our imagination. A Git branch is no longer just a reference to a Git commit, and if you’ve made a feature branch and then made a commit to that branch and merged that branch into any of the mainline branches. Git doesn’t keep this information on which branch was used to push that commit in the first place. Sometimes it is hard to navigate through Git history, and in reality, the picture above with some real Git log viewer will look more like a spaghetti of Git merge commits, and such view above it is rather a representation of the SVN branching model than a git one. I can assume that at the time when Git and Git-Flow appeared, people still worked a lot with SVN, and SVN branching still had a significant influence.

Use Cases

Actually, as you can see, it seems that Git-Flow is really covering all the use cases needed for modern development. However, digging into details holistically, we can see there are flaws with almost every detail. Let’s go one by one with use cases.

UC 1: You can do the development in your feature branch. However, long-lived feature branches and that divergence between master (main) and develop branches, it is actually required a certain effort to reproduce the production code version on your computer and integrate it with develop branch.

UC 2: History is there. However, the history will be cumbersome and hard to navigate, and plenty of merge commits will make things even harder

UC 3: Continuous Integration for the master branch is actually not fully happening as expected due to divergence between the master(main) and develop branches.

Long-living feature branches might happen and delay CI.

UC 4: Merging the process of developing the branch into the (master)main is going to be complicated and done reactively on issues that already happened in production.

Also, merging development into the master and code review of that merge becomes complicated because, at this point, there is no single responsible person for developing the branch since it is a collaborative branch and results from joint efforts.

In my experience, I was observing a situation during which a strong senior engineer was struggling to merge a developed branch altogether into a master, and the quality of that merge was really suffering in the end. Enough said…

UC 5, UC 6: Worth stating it again here, developing and the master(main) branches are most likely to diverge, and even that fact that it is possible to do the changes into different branches with the Git-Flow approach, the process is not entirely reliable.

UC 7: It is mainly coming with long-lived feature branches. With short-lived feature branches, it is not really an issue. However, according to Agile/Scrum, feature branches need to be merged and tested before the end of the iteration.

Git-Flow Alternatives

Git-Flow and its related complexity emerged due to the needs of the project teams. However, the main issue with Git-Flow is not the complexity, rather, it couldn’t handle certain situations reliably, and for that reason, other approaches exist.

Here are a couple of alternatives git branching strategies:

- GitHub-Flow

- Trunk-based development approach

I will be speaking shortly about these two GitHub-Flow and Trunk-based development approaches. The GitHub-Flow is likely because of its simplicity, while Git Trunk-based is quite developed and can handle all the use cases as Git-Flow does. However, it is made in a different way compared to Git-Flow and can overcome many Git-Flow issues described above.

Also, there is another practice called feature flag — it is not really a branching strategy, however greatly helps to maintain the use cases described above, and it is worth mentioning as it is very supportive in addition to the Git branching strategy.

Also, I would recommend going through this article since it has a lot of guidelines and different scenarios for different use cases.

GitHub-Flow Branching Strategy

For some certain projects, an entire git-flow process with develop and master(main) branches and multiple releases can be just overcomplicated, essentially that you maintain an open-source product hosted somewhere on the git hub, and you don’t have the actual capacity to maintain something more than one release.

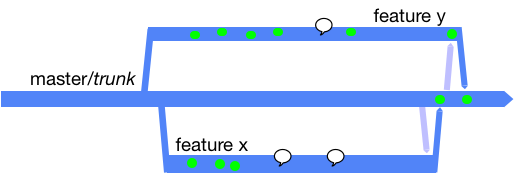

The main idea behind GitHub-Flow, it has only the master (main) branch and any changes are done through a feature branch like Git-Flow. However, feature branches are merged into the master(main) branch directly since there is no developed branch. GitHub-Flow is entirely supported by GitHub pull requests.

You need to maintain only the master (main) branch, and your branching model is greatly simplified compared to Git-Flow, and the overall process is much more reliable. However, it comes with a cost. You can’t actually separate development for production hotfix and release candidate, and UC 5, and UC 6 are not fully supported by GitHub-Flow.

However, regarding all the other use cases like UC 1, UC 2, UC 3, UC 4, UC 5.1, and UC 7 — it handles much better than Git-Flow and doesn’t have a Git-Flow drawback.

My advice: If you working on multiple projects, if you can choose different Git branching strategies for a different project, it is obviously beneficial to choose the branching strategy that works for a particular project the best way, and if you see that some of your projects don’t really require UC 5 and UC 6 — it will be much more reliable and save a lot of your time if you can just use GitHub-Flow for that project instead of Git-Flow.

Git Trunk-Based Development With the Branches

Git Trunk is a very developed Git branching model, and there are many different patterns for the different situations you can find on the URL here, and it can cover all the use cases listed above.

When I am hearing about trunks, it makes me nostalgic thinking about good old times when we used SVN with a trunk where all developers were committing their changes. Git is a more advanced technology than SVN, and once Git came to the market with a powerful branching system, it really changed the way we approach development and branching.

The most basic usage of the Git Trunk approach is that you have only the master (main) branch and all the team members pushing directly to there. It might feel a little bit extreme. Just push directly without any feature branch, code review, or some pre-CI process. However, I can assure you that a decade ago, most of the teams were working like that and created many great products. If you have a team where you trusting to each other like yourself, then why not do the same?

However, in this article, we going to cover Git Trunk-based development for more like enterprise development, where we want to address all the use cases above.

What I really love about the Git Trunk approach is that it is very flexible. You can start with a very basic like the above, and based on your needs, you can set up different levels of maturity of your process. While the approach is backward/forward compatible itself, if you started with some very basic level, you can always improve your process to the next level, and if the process seems overcomplicated, you can downgrade your approach.

UC 1, UC 2, and UC 3 individual contribution, history, and team collaboration are already fully addressed with basic Git trunk, and you don’t need any other branching rather than the master (main) for this.

To get started, you can easily clone the remote git repository into your working copy.

git clone git@github.com:amidukr/virtual-network-framework-js.git

git clone git@github.com:amidukr/virtual-network-framework-js.git

View the documents here.

Once you are done with your changes, just commit to your local Git clone, and merge with the upstream remote by pulling and then pushing into the remote.

git add .

git commit -m "Commit name"

git pull

git push

UC 4 Code Review: Perhaps giving access to everyone for your master (main) branch seems too risky for you, so perhaps you want to introduce some code review process, and for that reason, you might want to introduce the feature branches to your project, and it might look like GitHub-Flow now.

Whether it is a trunk-based approach or Git-Flow, you still can get into long-living feature branch issues. However, the main difference here is that the trunk-based approach explicitly guides you to do the short-living feature branches to encourage the typical trunk-based CI process.

To create a new feature branch from the latest master branch.

git checkout master

git pull

git checkout -b <branch>

Using just a Git command line without any tooling, merging feature branch is just simple like that: pull/merge from the master, and then push the merged version back into master:

git pull origin master:<feature-branch>

git push origin <feature-branch>:master

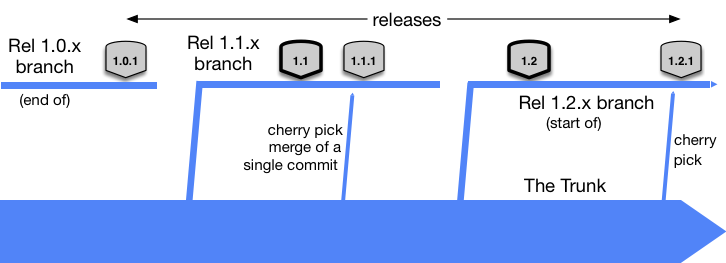

UC 5, UC 6 Maintaining multiple versions: In most simple scenarios, you don’t need to maintain many versions, so there is no reason to introduce any complexity where it is not needed, however the thing that is required here in order to keep version history, every time you make a release either internally release candidate or to production you need to mark git commit with a version tag.

git tag 0.0.16

Later on, when you are in a situation where you need to make a hotfix to production or to release a candidate while your master branch is far ahead of the release candidate, with Git, you can easily slice a branch of your tagged commit.

To make a fix, actually, there are two approaches:

- We can fix a bug on a master (main) branch and then cherry-pick it into the release branch.

- Or we can fix it in the release branch and merge the release branch into the main.

Actually, the first approach is more recommended because the trunk-based approach encourages maintaining the master (main) branch up-to-date and stable to be sure that issue is actually fixed for the product and will never happen in the future. Once it is fixed in the master(main) branch, it can be cherry-picked into the release branch.

The second approach can be used when issues on the release branch are hard to reproduce from the master (main) branch.

The entire process with the feature branch will look like the following:

# Creating relesae branch if it is not exists yet

git checkout -b release-0.0.16 0.0.16

# Creating branch for hotfix

git checkout master

git pull

git checkout -b <hotfix-branch>

# do the necessary fixes on the working copy

git commit -m "Commit message goes here"

git pull origin master:<hotfix-branch>

# Request for team code review and push the change once approve

git push origin <hotfix-branch>:master

# or use GitHub pull request to merge it back

# Cherry picking change into release branch

git checkout release-0.0.16

git cherry-pick -m <master-parent-number> <master-merge-commit-sha>

git push origin release-0.0.16

Even if a divergence appears between some of the release branches and the master (main) branch, unused previous release branches will be removed eventually. The main effort of trunk based approach is to maintain the master (main) branch as stable, so any issue in the past release shouldn’t be happening again and be fixed in the master (main) in the first place.

Quite often, the release branches are not really needed. If you have a strong team, who made all necessary testing in a lower environment, and there is no production incident, there is no reason to slice a release branch of the tag, and the team can just keep going with the master branch. Slicing the release branch is only needed in case of a production emergency.

UC 7 Alignment with Scrum: From the iteration release and production release — trunk based approach also fits well since, with release branches, it is still possible to do development and production support in parallel. The team can work with iteration as usual in the master (main) branch, and it is up to management to decide when they want to go into production.

It could be a situation when QA can take a little bit longer on testing of release candidate version. The process is really like the above with production hotfix. In most simple cases, the git tag is the only needed thing; however, if change/fix is required to release the candidate version in QA/UAT, then the process is the same make sure the master has the necessary fix and cherry-pick it into release candidate branch before releasing for testing.

Trunk-based versus Git-Flow divergence: as you can see here with the trunk-based approach since every new release really starts from the git tag that exists on the master branch, there is no initial such a situation as divergence, and even if that divergence already happened between master and release branch, it will never be repeated again with subsequent releases, since release branch always sliced from tag on the master branch, and the process encouraging to fix the problem first in master branch.

With the Git trunk approach, literally every exact commit that is being deployed to the production/release candidate comes through CI the process, and eventually developer was able to check out to his local computer and do the necessary testing and fixing before it created the problem in production.

Also, you can see that the trunk-based approach has the same level of flexibility compared to git-flow. Actually, it is possible to do the maintenance of multiple versions at once, and the trunk-based approach can support the same level of maturity with the application development process, like code review, quality practices, versioning, etc. However, it doesn’t have certain Git-Flow flaws.

Real-World Examples

Who uses trunk-based development? I think I have a very good example. Spring is a very well-known project in the Java community with a long history, and many supported modules and release versions. The Spring community has an article describing its branching model, and they do not say explicitly that it is trunk-based development. However, the fact they keep releasing branches and cherry-picking from the main (master) branch into there makes it really looks like it is so.

Spring Boot seems to have a little bit more sophisticated branching policy compared to Spring Framework. However, the core part critical fixes are done in the main (master) branch and then cherry-picked into release.

There is something non-canonical to trunk-based development in Spring Boot. They do no-off merges between release branches because they need to support multiple release branches.

So technically, it is not exactly trunk-based development and not Git-Flow for sure. However, it shares more similarities with the trunk-based approach. The fact that their release branches are long-living can lead to a similar situation to Git-Flow. However, the release branch will be abandoned eventually, and all its issues will go away eventually with that branch, taking advantage of trunk-based development.

Feature Flags

The feature flag is not really a branching strategy and is not related to Git in general. However, it has great support to maintain differences and sometimes simplify branching and releasing.

A feature flag is just another setting to the application that enables/disables certain features. Typically, applications already have the tooling to support different configurations across different environments; for example, the database instance is quite often different for prod and non-prod environments. Production setups may have different configurations for performance tweaks. And feature flag is just another setting like that. It could be just a boolean flag that can enable/disable application features in different environments.

Actually, in my practice, I’ve used feature flags a lot in situations when we needed to deliver some critical functionality. However, we couldn’t enable it because we were waiting for third-party dependency. We were able to test it well with third-party in the lower non-prod environment. However, our release cycle was running on a different schedule. And with the use of the feature flag, I was able to deliver the functionality in production proactively, and once the third-party dependency became available in production, enabling functionality was as easy as changing the flag, and actually at this moment, I was very confident that enabling the feature flag will not destroy something because to that moment everything was fully tested in lower environments with that flag enabled.

If you want to do the same thing with Git-Flow, perhaps in the situation above, you would want to create the feature branch and deploy the feature branch once 3rd-party is available. However, in this case, a hotfix is a shortcut that skips many steps of the CD pipeline. With the feature flag, it is just another mainstream development which will go through all the CI/CD stages. The code will be available on every mainline branch so the team can test and integrate this feature in other environments.

However, it comes with a certain cost since application configuration becomes more complex and leads to dead code in the application logic for obsolete feature flags that need to be cleaned up eventually to clean up an application from dead code.

If you want to learn more about feature flags, here are some readings:

Published at DZone with permission of Dmytro Brazhnyk. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments