A Guide to SQL Naming Conventions

What's in a [SQL] name?

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For Free

One of Java's big strengths, in my opinion, is the fact that most naming conventions have been established by the creators of the language. For example:

- Class names are in PascalCase

- Member names are in camelCase

- Constants are in SNAKE_CASE

If someone does not adhere to these conventions, the resulting code quickly looks non-idiomatic.

You may also like: How to Properly Format SQL Code

What About SQL?

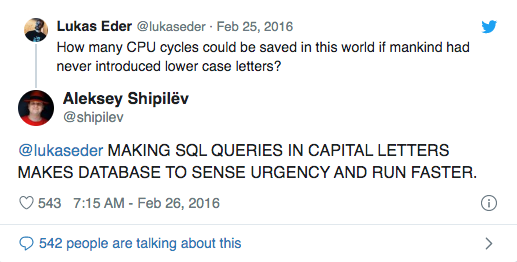

SQL is different. While some people claim UPPER CASE IS FASTEST:

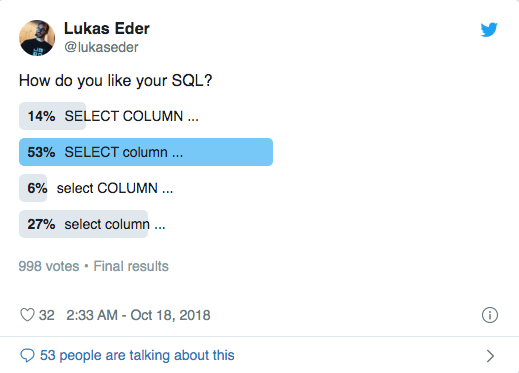

Others do not agree on the "correct" case:

There seems to be a tendency towards writing identifiers in lower case, with no agreement on the case of keywords. Also, in most dialects, people prefer snake_case for identifiers, although in SQL Server, people seem to prefer PascalCase or camelCase.

That's for style. And I'd love to hear your opinion on style and naming conventions in the comments!

What About Naming Conventions?

In many languages, naming conventions (of identifiers) is not really relevant, because the way the language designs namespacing, there is relatively little risk for conflict. In SQL, this is a bit different. Most SQL databases support only a 3-4 layered set of namespaces:

- Catalog

- Schema

- Table (or procedure, type)

- Column (or parameter, attribute)

Some dialect dependent caveats:

- While SQL Server supports both catalog AND schema, most dialects only support one of them

- MySQL treats the catalog ("database") as the schema

- Oracle supports a package namespace for procedures, between schema and procedure

In any case, there is no such concept as package ("schema") hierarchies as there is in languages like Java, which makes namespacing in SQL quite tricky. A problem that can easily happen when writing stored procedures:

FUNCTION get_name (id NUMBER) IS

result NUMBER;

BEGIN

SELECT name

INTO result

FROM customer

WHERE id = id; -- Ehm...

RETURN result;

END;As can be seen above, both the CUSTOMER.ID column as well as the GET_NAME.ID parameter could be resolved by the unqualified ID expression. This is easy to work around, but a tedious problem to think of all the time.

Another example is when joining tables, which probably have duplicate column names:

SELECT *

FROM customer c

JOIN address a ON c.id = a.customer_idThis query might produce two ambiguous ID columns: CUSTOMER.ID and ADDRESS.ID. In the SQL language, it is mostly easy to distinguish between them by qualifying them. But in clients (e.g. Java), they are less easy to qualify properly. If we put the query in a view, it gets even trickier.

"Hungarian Notation"

Hence, SQL and the procedural languages are a rare case where some type of Hungarian notation could be useful. Unlike with hungarian notation itself, where the data type is encoded in the name, in this case, we might encode some other piece of information in the name. Here's a list of rules I've found very useful in the past:

1. Prefixing Objects by Semantic Type

Tables, views, and other "tabular things" may quickly conflict with each other. Especially in Oracle, where one does not simply create a schema because of all the security hassles this produces (schemas and users are kinda the same thing, which is nuts of course. A schema should exist completely independently from a user), it may be useful to encode a schema in the object name:

Besides, when using views for security and access control, one might have additional prefixes or suffixes to denote the style of view:

This list is obviously incomplete. I'm undecided whether this is necessarily a good thing in general. For example, should packages, procedures, sequences, constraints be prefixed as well? Often, they do not lead to ambiguities in namespace resolution. But sometimes they do. The importance, as always, is to be consistent with a ruleset. So, once this practice is embraced, it should be applied everywhere.

2. Singular or Plural Table Names

Who cares. Just pick one and use it consistently.

3. Establishing Standard Aliasing

Another technique that I've found very useful in the past is a standard approach to aliasing things. We need to alias tables all the time, e.g. in queries like this:

SELECT *

FROM customer c

JOIN address a ON c.id = a.customer_idBut what if we have to join ACCOUNT as well? We already used A for ADDRESS, so we cannot reuse A. But if we don't re-use the same aliases in every query, the queries start to be a bit confusing to read.

We could just not use aliases and always fully qualify all identifiers:

SELECT *

FROM customer

JOIN address ON customer.id = address.customer_idBut that quickly turns out to be verbose, especially with longer table names, so also not very readable. The standard approach to aliasing things I've found very useful is to use this simple algorithm that produces four-letter aliases for every table. Given the Sakila database, we could establish:

The algorithm to shorten a table name is simple:

- If the name does not contain an underscore, take the four first letters, e.g

CUSTOMERbecomesCUST - If the name contains one underscore, take the first two letters of each word, e.g. becomes

FIAC - If the name contains two underscores, take the first two letters of the first word, and the first letter of the other words, e.g. becomes

FICD - If the name contains three or more underscores, take the first letter of each word

- If a new abbreviation causes a conflict with the existing ones, make a pragmatic choice

This technique worked well for large-ish schemas with 500+ tables. You'd think that abbreviations like FICD are meaningless, and indeed, they are, at first. But once you start writing a ton of SQL against this schema, you start "learning" the abbreviations, and they become meaningful.

What's more, you can use these abbreviations everywhere, not just when writing joins:

SELECT

cust.first_name,

cust.last_name,

addr.city

FROM customer cust

JOIN address addr ON cust.id = addr.customer_idBut also when aliasing columns in views or derived tables:

SELECT

cust.first_name AS cust_first_name,

cust.last_name AS cust_last_name,

addr.city AS addr_city

FROM customer cust

JOIN address addr ON cust.id = addr.customer_idThis becomes invaluable when your queries become more complex (say, 20-30 joins) and you start projecting tons of columns in a library of views that select from other views that select from other views. It's easy to keep consistent, and you can also easily recognize things like:

- What table a given column originates from

- If that column has an index you can use (on a query against the view!)

- If two columns that look the same (e.g.

FIRST_NAME) really are the same

I think that if you work with views extensively (I've worked with schemas of 1000+ views in the past), then such a naming convention is almost mandatory.

Conclusion

There isn't really a "correct" way to name things in any language, including SQL. But given the limitations of some SQL dialects, or the fact that after joining, two names may easily conflict, I've found the above two tools very useful in the past: 1) Prefixing identifiers with a hint about their object types, 2) Establishing a standard for aliasing tables, and always alias column names accordingly.

When you're using a code generator like jOOQ's, the generated column names on views will already include the table name as a prefix, so you can easily "see" what you're querying.

I'm curious about your own naming conventions, looking forward to your comments in the comment section!

Further Reading

Published at DZone with permission of Lukas Eder. See the original article here.

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments