6 Easy Ways to Start Coding Accessibly

Coding accessibly might seem intimidating at first, but once you dip your toes in the water, you’ll quickly see that it’s not so scary after all.

Join the DZone community and get the full member experience.

Join For FreeWhy Does Accessible Development Feel So Intimidating?

I’ve found accessible development to be one of the places where it’s easiest to fall into analysis paralysis: there’s always something that you feel like you need to double-check first, something that you heard someone else is doing, or just a vague feeling that you don’t really know enough yet to start tackling accessible coding yourself. Just one more blog, one more conference talk, one more video, and then you’ll be ready to start writing accessible code.

Meanwhile, our applications – and more importantly, our users – are stuck with the same old inaccessible code that we just keep writing. The best thing we can do is to start writing accessible code to the best of our ability, with the acknowledgment that we might make a mistake! After all, isn’t that just how development works all the time? We code things using the skillset we have, adhering to the best practices that we’re aware of and the current web standards. Sometimes we make mistakes, whether those are bugs or architecture approaches we would have done differently in hindsight, but we still ship an application that’s (hopefully) mostly functional. Accessibility is the same way: it functions on a sliding scale, not an on/off switch. We code accessible features as we’re able, based on what we know right now and the current accessibility-related guidance. It might not be perfect 100% of the time, but anything is better than ignoring accessibility entirely. And hey, code isn’t carved into stone, right? You can always go back and update something once you’ve learned how to do it better.

It can be easy to build up the idea of coding accessibly in our heads into something so large and intimidating that we can always find an excuse for putting it off. But in reality, accessible code is a series of small to moderate adjustments to your development and testing process that are all completely doable by developers of all experience levels. After all, as developers, learning new stuff is just part of our job. When your team decided to switch from JavaScript to TypeScript or start using React Hooks, you probably picked it up after a bit without too much pain. Frameworks, libraries, best practices, even languages themselves change and evolve over time. Once you start thinking of accessibility the same way and recognize that it’s not an optional upgrade, you can start to build accessible development into your existing processes and patterns at work.

How Do I Start?

The best way to start is to start small and work up. If you’re working in a naturally component-based application (like an Angular or React app), this approach works especially well because you naturally have your application broken down into those building blocks. You can start adding accessibility features to your base components, then get it for “free” as you scale and use those components in other components (and then those components in other components, etc.). It also helps the task feel less intimidating. The whole application doesn’t have to be perfectly accessible today; today we’re making an accessible button. But then that button will get used everywhere in your app, and just like that, you’ve made a huge accessibility upgrade!

Pick out a handful of your base elements that get used over and over throughout your application. Then, you can run a quick accessibility check on each one by looking at your code and asking the following:

1. Does This Component Use Semantic HTML?

The single most powerful way you can improve accessibility in your application is to make sure you’re always using the correct semantic element for the job. Semantic HTML helps tell screen readers what they’re looking at, makes keyboard navigation easy, and intrinsically organizes your page. When we open a website or app, we usually do a quick visual skim over the contents to quickly find what we need. Your visually impaired users can’t always do that, but their screen readers can. Screen readers can read out headings for sections and allow users to skip ahead, inform users what they can interact with by looking for buttons, read out content in list format, quickly navigate menus, forms, and more; but only when you’ve used the right elements, and not just thrown a div on everything.

Image from https://www.w3schools.com/html/html5_semantic_elements.asp

You’re probably already familiar with a handful of common semantic HTML tags: the text-related tags (h1 through h6 and p) are probably the most well-known, although button or img might give them a run for their money. In addition to those, your application will benefit from using nav for your navigation, header and footer (which do exactly what they say on the tin), main, section, article, and aside to define your content, forms for user-input forms, and table for data tables. Thankfully, the days of tables for layout are long behind us (as long as you’re not coding an email). There are some less-common ones as well, such as progress for progress bars, or cite for the title of a work. It’s worth getting acquainted with the current list of available HTML5 elements if you aren’t already. The more you can use correct semantic tags, the more accessible your application will become.

If that wasn’t enough reason, you’ll also find that a semantically written document is a lot easier for your developers to quickly parse and work with as well because they can see at a glance what each element does and why it’s there, so it will speed up your dev time and ease your onboarding, too! Semantic HTML updates are easy to make, just swapping one element for another, and they don’t usually create many (if any) breaking changes. It’s really a quick win all around, and a wonderful way to immediately improve your accessibility!

2. Do All Images Have Alt Text?

If you’re looking for another quick win, you can do a search through your components for img tags. If they don’t all include alt text, then you have another straightforward way to level up your accessibility game!

Alt text, short for alternative text, is descriptive text that tells a visually impaired user (or just one who can’t load your images) what’s being shown in the picture. If you’ve ever opened an email where the images haven’t been downloaded yet, you’ve seen alt text in action! To add it to your images, you’ll just want to add the alt property to your img tag, like so:

<img src

There are a few guidelines to keep in mind when writing good alt text:

You don’t need to include “Image of” or “Photo of.” That’s implied information. The only time you might need to call out the medium would be for illustrations, paintings, or other works of art where that’s important context for your user.

You should only include blank alt text when the image is a decorative image. In most cases, alt="" is a pattern to be avoided. The exception to that rule is when you have a purely artistic element on your page. Things like borders, dividing lines, and other things added to make the page look pretty, but communicate no information or value to the user.

Be descriptive! They say a photo is worth a thousand words, so make sure you’re not using just one or two to try and describe a whole image. alt="Cake" is significantly less helpful than alt="A chocolate cake with candles, in front of a small girl wearing a birthday hat and a pink dress." One paints a much more exact and descriptive picture of the image in question.

Include any relevant text in the image. It’s generally a bad practice to use images of text, but sometimes you have an image that just happens to have relevant text included: maybe a photo of a sign or a book title. In those cases, make sure you include the text in your alt, so your users don’t miss that info.

3. Have We Made Accessible Color Choices?

Color is powerful, no doubt about it. However, it’s important for us to remember that color also isn’t always accessible to all our users. The first users you might think about in this situation might be your blind or colorblind users, but keep in mind that it’s not just them; the intent of your chosen colors can also be affected for users who have nightshift enabled, who can’t see their device clearly while standing in bright sunlight, or who are looking at their phone with sunglasses on, for example. Making accessible color choices is a benefit to all your users, and well worth your time.

When you’re choosing colors for your various UI elements, it’s important to make sure you’re meeting an accessible standard for color contrast. The WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) defines three levels of “passing” color contrast ratios: failing, AA, and AAA. AA level means your colors have enough contrast to be readable but might still present problems for some users. AAA level means you have achieved extremely high contrast that should be readable for most of your users. You should always aim for AAA compliance but making sure you’re not failing is a good starting point.

You can check your color contrast levels using any number of online tools – my personal favorite is the Adobe Color Contrast Checker (which includes an excellent Color Blindness tool as well). There, you can input your foreground and background colors and let them take the guesswork out of figuring out your color contrast ratio!

Screenshots from https://color.adobe.com/create/color-contrast-analyzer

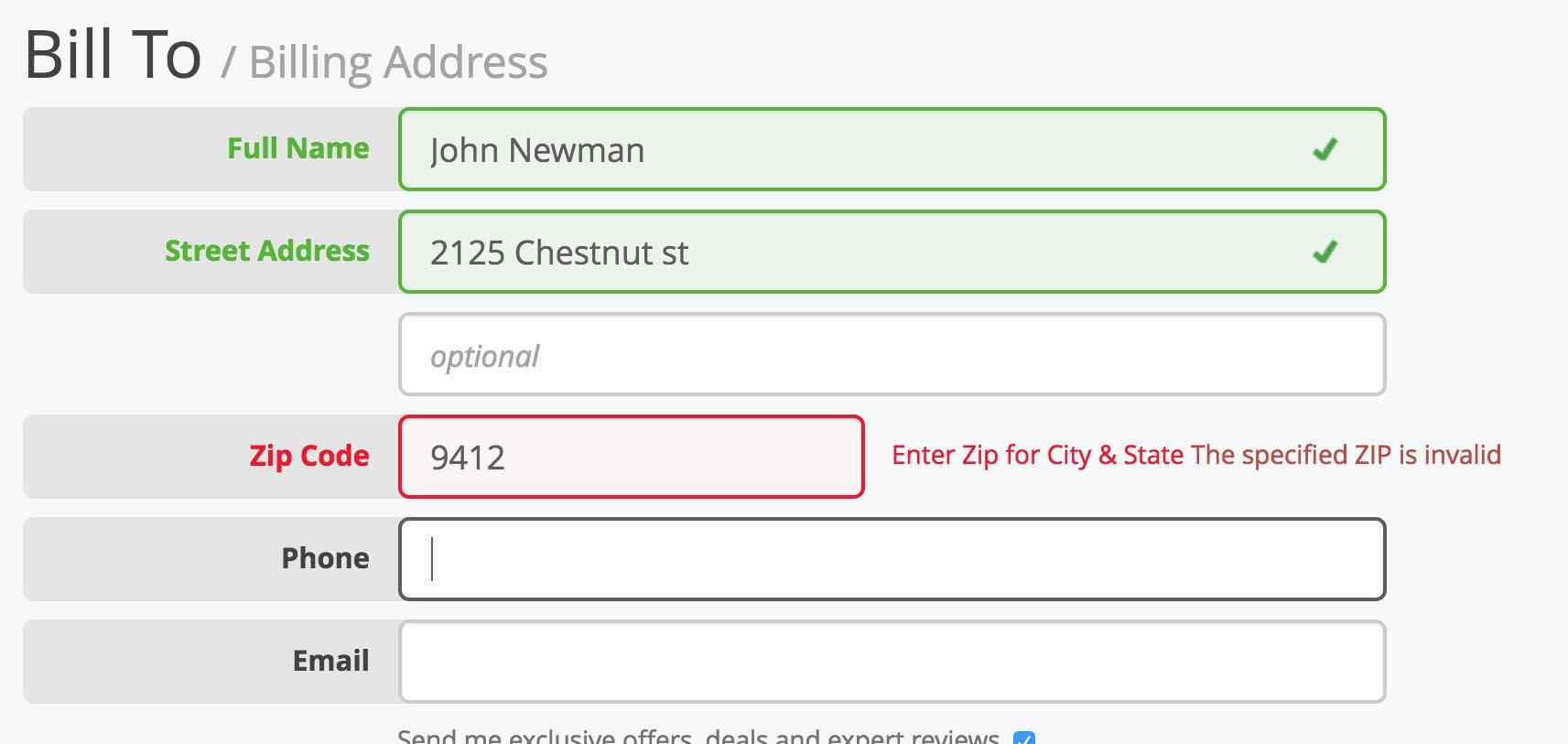

The other important aspect of accessibility and color is ensuring that you’re not communicating any information through color alone. This is a dangerously easy trap to fall into, unfortunately.

One of the easiest examples to think about are forms. How many times have you seen a form that changes the border color of an input element to red to signify failed validation? It’s not such a terrible thing to do, if you also make sure to include an icon, text, or another element to show the user that something isn’t right. If you’re relying on the red border color alone, there’s a sizable percentage of your users who will struggle to figure out why their form can’t be submitted.

Bad Example

Image from https://stackoverflow.com/questions/16471589/javascript-form-validation-with-class

Good Example

Image from https://baymard.com/blog/inline-form-validation

4. Can I Navigate This Content Using my Keyboard?

Another good base-level accessibility check is to try and use your own components, but without ever touching your mouse. Keyboard navigation is a huge part of accessibility because there are many reasons why using a mouse might not be practical or possible for your users: blindness, limb deformity and loss, or lack of fine motor control, for example. Some power users might also simply prefer to use their keyboard exclusively because it’s faster and more efficient than using a mouse. I’ve met tons of developers who can code all day without reaching for their mouse, so why not offer that same option to your users? It’s another notable example of how accessibility isn’t an edge case; accessible features benefit the entirety of your userbase.

The good news is that keyboard nav is a feature you’ll get for free with good ol’ HTML and CSS. Semantic HTML plays a crucial role here too, allowing your users to jump between interactive elements, toggle on and off checkboxes, navigate dropdown menus, scroll, and so much more, but only if you’ve used the actual HTML elements for all those things. If your “button” is actually a div with an onClick action, then you’ve just lost all that sweet, sweet built-in accessibility! It is possible to make those elements accessible, using ARIA landmarks and forced focus indicators, but you’ll have a far easier and faster time if you don’t try and reinvent the wheel.

When you’re checking your keyboard navigability, keep an eye out for the following:

Can you see a visual indicator of which item you’re currently focused on? These focus indicators will appear naturally unless you’ve overwritten them by setting your element’s outline styles to 0 or none. You can change the focus style if you’d like it to better match your brand look and feel, but don’t remove it entirely and always ensure it’s not too subtle!

Can you focus on any elements that aren’t interactive? Users should only be able to focus on an element that they can interact with in some way. You can force elements to be focusable by using tabindex, but if your user can’t interact with it then you should make sure that’s not being applied.

How long does it take to navigate the page using a keyboard? It shouldn’t be a hassle for your users to have to tab through a bunch of stuff to get to the element they need. Make sure you’re using semantic HTML to break your page up into smaller sections (main, article, nav, etc.), as well as offering jump links to content further down the page, if needed.

Does the keyboard navigation follow the visual flow of the page? As you work your way through a page on your keyboard, the focus should follow the content: top to bottom, left to right (or right to left if the content is in an RTL language such as Hebrew). Again, this is something that should happen naturally if you’ve structured your underlying HTML correctly. Remember that HTML should handle the structure and organization and CSS should handle the visual adjustments (if needed).

5. Do I need ARIA attributes?

ARIA attributes can be one of the more confusing aspects of accessible coding, so let’s see if we can clear it up a little! ARIA stands for “Accessible Rich Internet Applications”, and ARIA attributes exist so that more complex widgets and custom tools can be accessibly used. A lot of the confusion around ARIA attributes comes from how they were historically used, which isn’t necessarily the same today. In HTML4, there were far fewer semantic elements. If a developer wanted to include an interactive element that didn’t have an existing HTML tag, they had to create it themselves and then augment it with ARIA attributes to achieve full accessibility. Now, there are fewer and fewer cases where this is necessary, because of the wide variety of HTML5 elements – and by extension, the need for ARIA attributes has lessened (as long as you’re coding semantically). If you use a native HTML5 element, you do not need to include ARIA attributes: those features are already built-in. For that reason, developers should always use the semantic HTML element when possible.

There are situations where ARIA attributes are still useful. Here are a few of the most common:

Using ARIA Live to announce content changes. In modern applications, it’s common for new content to appear on the screen after the initial page load has been completed, such as a feed that updates automatically, or a notification. These might be obvious to some users but won’t be for those using screen readers. Including aria-live allows you to denote regions on your page where you will load dynamic content, basically telling the assistive technology to keep an eye on this space for updates. You can set aria-live to be either polite or assertive. This determines whether the screen reader will wait for the next idle period to announce the content update or interrupt the user to announce it immediately. As you might imagine, polite should always be what you reach for, unless the announcement is truly immediate and urgent.

<div id="notification" aria-live="polite"> <p>New notifications will populate here</p> </div>ARIA Labels for elements that don’t include text. A common example here is a button that uses an icon for identification, but no text. In this case, you should include aria-label to give your element an accessible name.

<button aria-label="Submit form"> <img src="enter-icon.png"> </button>- ARIA Roles for elements that don’t have a semantic equivalent. If you’re creating a custom widget that you can’t use the built-in HTML5 elements for, you should tell your users what your element does by assigning it an aria-role. This provides your users with added context to help understand your layout.

<div aria-role="toolbar">

<button>Edit</button>

<button>Save</button>

<button>Refresh</button>

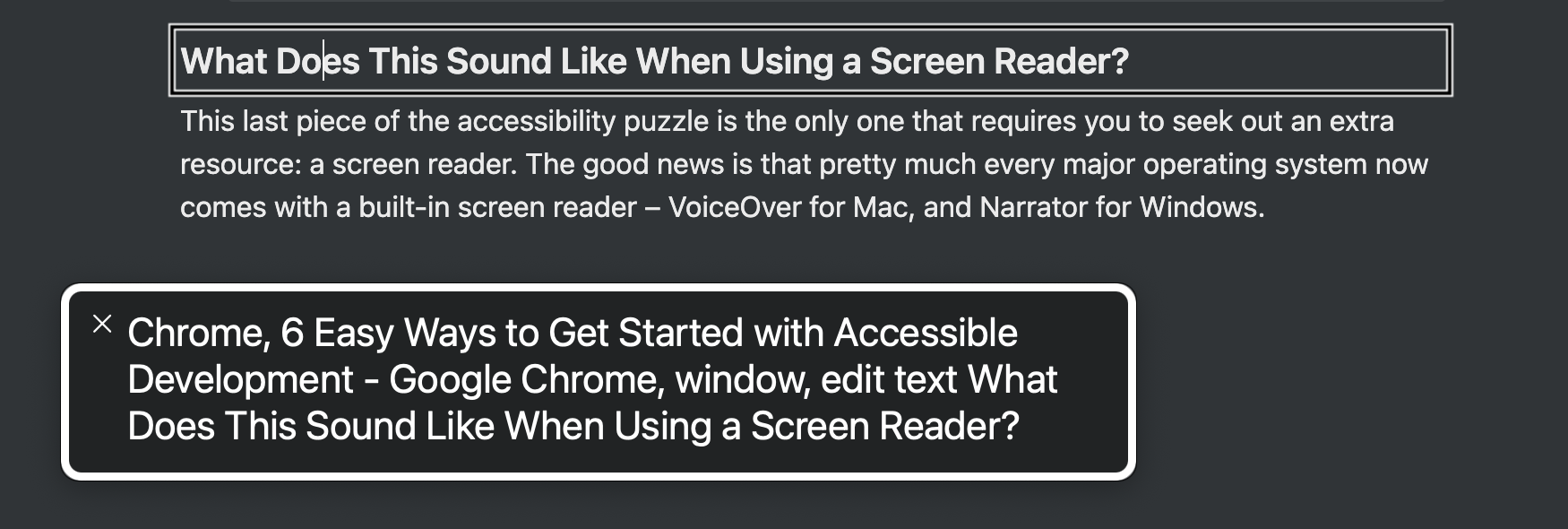

</div> 6. What Does This Sound Like When Using a Screen Reader?

This last piece of the accessibility puzzle is the only one that requires you to seek out an extra resource: a screen reader. The good news is that pretty much every major operating system now comes with a built-in screen reader, the two most common being VoiceOver for Mac, and Narrator for Windows. You can turn these on in the System Preferences for your operating system and then navigate as you normally would and listen to your components!

This is an especially powerful test when combined with keyboard-only navigation. You’ll immediately get a feel for what’s difficult to navigate and how much content is read aloud as you try to complete a task. I highly encourage you to walk a mile in your users' shoes by spending at least a day (but ideally longer – maybe even a full week?) going about your work with the screen reader turned on. You might be surprised by what your application sounds like!

Ready To Get Started?

Coding accessibly might seem intimidating at first, but once you dip your toes in the water, you’ll quickly see that it’s not so scary after all. It’s one of those topics where it can be easy to fall down the rabbit hole - there’s a lot of great accessibility-related content out there – but make sure you’re not getting stuck in the research phase and putting off the actual implementation. Any improvements you can make are better than ignoring accessibility entirely. Break it down into manageable chunks and start implementing some of the ideas above. Accessibility features benefit all your users, so make sure you’re not skipping out on these great ways to improve the usability of your app!

Opinions expressed by DZone contributors are their own.

Comments